Natural Language Processing (NLP) often exists at a crossroads between engineering and linguistics. On one side, we have models designed to process text efficiently; on the other, we have the deep, complex theories of how human language actually works. One of the most successful attempts to bridge these worlds is Universal Dependencies (UD).

UD is a massive global initiative to create a standard way of annotating the grammar (syntax) of all human languages. If you are training a parser to understand sentence structure, UD is likely the framework you are using. However, despite its name, Universal Dependencies has faced criticism for not being truly “universal” in the eyes of linguistic typologists—scholars who study the structural similarities and differences across languages.

In the paper “Contribution of Linguistic Typology to Universal Dependency Parsing,” researcher Ali Basirat investigates a fascinating question: If we modify UD to strictly follow linguistic typology principles, does it make it easier for computers to parse language?

The answer is a compelling yes. This post will walk you through the problems with the current standard, the typologically motivated solution proposed, and the empirical results showing that better linguistics can lead to better engineering.

The Problem: Is Universal Dependencies Actually Universal?

Since its release in 2014, Universal Dependencies has become the standard for morphosyntactic annotation. Its goal is to provide a consistent annotation scheme so that a parser trained on English might share structural logic with a parser trained on Persian or Finnish.

However, critics, including linguist William Croft, have argued that UD deviates from typological principles. Typology is the study of linguistic universals—patterns that hold true across most or all languages. Critics argue that UD often relies on language-specific strategies (often biased toward European languages) rather than truly universal grammatical functions.

For example, UD might tag a specific relationship based on how English handles it morphologically (using a specific word form), whereas a typological approach looks at the function of that relationship, regardless of how a specific language encodes it.

Croft et al. (2017) proposed a revision to UD to fix these theoretical gaps. Until this study, however, it was unclear whether this theoretical purity would actually help NLP models in practice. Would a more “linguistically correct” treebank be harder or easier for an AI to learn?

The Solution: A Typologically Informed Transformation

The researchers tested this by applying a transformation to existing UD treebanks. They call this new scheme TUD (Typological Universal Dependencies).

It is important to note that this transformation fundamentally changes the labels of the dependencies (the names of the relationships between words) but preserves the topology (the actual shape of the tree structure).

The transformation is based on four design principles proposed by Croft:

- Distinguish Universal Constructions: Avoid labels based on language-specific strategies (like English copulas).

- Same Label for Same Function: If two structures do the same syntactic work, they should have the same label.

- Prioritize Information Packaging: Group modifiers that provide similar types of information under a single label to create a more economic tag set.

- Respect Dependency Ranks: Differentiate between arguments, modifiers, and secondary predicates based on their hierarchy.

Visualizing the Transformation

To implement these principles, the researchers devised a script to convert standard UD labels into TUD labels. This involves two types of moves: Consolidation (merging multiple UD labels into one TUD label) and Fragmentation (splitting one UD label into multiple TUD labels).

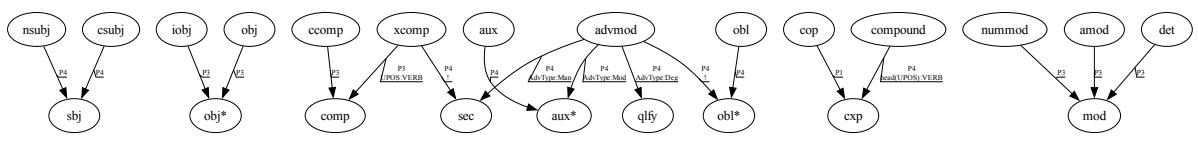

As shown in Figure 1, the transformation logic flows from the original UD labels (left/bottom nodes) to the new TUD labels (target nodes). Let’s break down the most critical changes illustrated in the diagram:

1. The “Subject” Consolidation

In standard UD, subjects are split into nominal subjects (nsubj) and clausal subjects (csubj). Typologically, however, a subject functions as a subject regardless of whether it is a noun phrase or a clause.

- Transformation:

nsubj+csubj\(\rightarrow\)sbj - Why? This adheres to the principle of “same label for same function.”

2. The “Object” Simplification

UD distinguishes between direct objects (obj) and indirect objects (iobj). Croft argues this distinction is often redundant for information packaging.

- Transformation:

iobj+obj\(\rightarrow\)obj* - Why? It streamlines the tag set. The parser no longer needs to struggle with the ambiguity between direct and indirect objects when the distinction isn’t strictly necessary for the dependency structure.

3. The “Modifier” Merger

Perhaps the most aggressive consolidation involves modifiers. UD has specific tags for determiners (det), numeric modifiers (nummod), and adjectival modifiers (amod).

- Transformation:

det+nummod+amod\(\rightarrow\)mod - Why? These all serve the broad function of modifying a noun. By grouping them, the model focuses on the head-dependent relationship rather than the specific part-of-speech category of the dependent.

4. The “Adverb” Fragmentation

While the previous rules merged labels, the treatment of adverbs adds complexity. UD lumps almost everything under advmod. However, adverbs vary wildly in function—some indicate manner (“quickly”), others degree (“very”), and others modality (“probably”).

- Transformation:

advmodsplits intosec(manner),qlfy(degree/hedging),aux(aspect/modality), andobl(location/time). - Why? This respects the “Dependency Ranks” principle. It attempts to capture the semantic reality that a manner adverb functions differently than a modal adverb.

Experimental Setup

To determine if TUD is actually better for parsing than UD, the authors conducted a rigorous empirical investigation.

The Data

They selected 20 languages from the UD 2.12 collection, covering diverse language families including Indo-European (English, Persian, Hindi), Afro-Asiatic (Arabic), Sino-Tibetan (Chinese), and Uralic (Finnish). This diversity is crucial to ensure the results aren’t just an artifact of one specific language type.

The Models

They trained two types of state-of-the-art dependency parsers:

- Transition-based Parser (UUParser): Builds the parse tree step-by-step.

- Graph-based Parser (Biaffine): Scores every possible edge between words and finds the best tree structure.

The Metric

The primary metric used was LAS (Labeled Attachment Score). This measures the percentage of words where the parser correctly predicted both the head (the parent word) and the label (the relationship type).

The Control: Random Transformation

This is a critical part of the study design. Since TUD involves merging many labels (consolidation), the total number of labels decreases. Generally, classification tasks are easier when there are fewer classes to choose from.

To prove that improvements were due to linguistic typology and not just having fewer labels, the researchers created a “Random” (RND) baseline. They randomly merged and split labels to match the statistical “impact rate” of the TUD transformation. If TUD beats RND, we know the linguistic logic is providing the value, not just the math.

Results: Does Typology Help?

The results provide a validation of Croft’s typological framework. The transformed TUD treebanks were generally easier to parse than the original UD treebanks.

Overall Performance Improvement

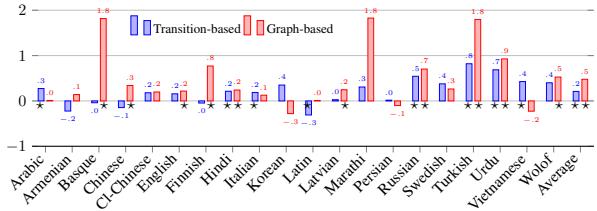

Figure 2 displays the absolute improvement (or degradation) in LAS across the tested languages. The blue bars represent the transition-based parser, and the red bars represent the graph-based parser.

- Positive Impact: For the vast majority of languages, the bars are positive, indicating that TUD improved accuracy.

- Graph-based Gains: The graph-based parser (Red) saw significant gains, with improvements reaching up to 2 points for some languages.

- Statistical Significance: The numbers next to the bars represent the LAS change. In languages like Hindi, Italian, and English, the improvements are statistically significant.

- The “Oracle” Potential: The researchers noted that if the transformation could be perfectly predicted, the potential gain was up to 3.0 LAS points. The models achieved roughly 0.5 points of this, showing that while the scheme is better, the transition is complex for the machine to learn perfectly.

Comparing to Random Baselines

Crucially, when compared to the RND (Random) baseline, TUD consistently outperformed it. This confirms that the semantic and functional grouping of labels is what aids the parser. Simply merging random labels does not yield the same benefit, proving that the typological principles align with the latent structures the AI is trying to learn.

Why Did It Work? Analyzing the Rules

Not all transformations were created equal. The study dissected which specific rule changes contributed to the success and which ones hurt performance.

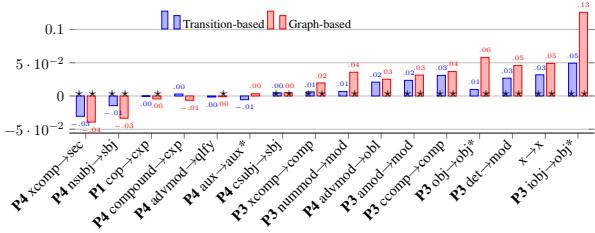

Figure 3 breaks down the contribution of individual transformation rules. This chart is revealing because it highlights the tension between Consolidation and Fragmentation.

The Winners: Consolidation Rules

Look at the right side of Figure 3. The rules with the highest positive impact are almost exclusively consolidation rules:

iobj -> obj*(+0.13): Merging indirect and direct objects was the biggest winner. In many languages, the distinction is subtle and structurally ambiguous. removing the distinction allows the parser to focus on the fact that it is an object, rather than which type of object it is.ccomp -> comp: Merging clausal complements also provided a strong boost.det -> mod&amod -> mod: Treating determiners and adjectives simply as “modifiers” helped the graph-based parser significantly.

These merges work because they reduce “noise.” They group functionally similar items, making the decision boundaries clearer for the neural network.

The Losers: Fragmentation Rules

Now look at the left side of Figure 3. The rules that hurt performance were the fragmentation rules:

advmod -> qlfy/xcomp -> sec: These rules attempt to split adverbs and complements into finer-grained semantic categories (like distinguishing a manner adverb from a degree adverb).- The Problem: While linguistically accurate, these distinctions are very hard to predict based purely on syntax. Without explicit morphological markers (which were often missing or inconsistent in the data), the parser struggled to guess which specific subtype of adverb was present.

This creates a trade-off. Typology suggests we should make these distinctions, but without richer data (like extensive morphological features), the parser finds it harder to learn them.

Conclusion and Implications

This study offers a compelling argument for the role of linguistic theory in modern AI. In an era where “more data” is often the default solution, Basirat’s work shows that “better data design” is equally powerful.

By aligning the Universal Dependencies scheme with the principles of linguistic typology—specifically by grouping labels based on function and information packaging—we can create treebanks that are not only more theoretically sound but also practically easier for machines to parse.

Key Takeaways:

- Typology Matters: Aligning annotation schemes with cross-linguistic universals improves computational performance.

- Consolidation Helps: Merging labels that perform the same function (like different types of objects or modifiers) significantly boosts accuracy by reducing ambiguity.

- Fragmentation is Risky: Splitting labels to capture semantic nuance (like types of adverbs) can hurt performance if the underlying data lacks the morphological clues to support those distinctions.

The paper concludes by suggesting that future versions of Universal Dependencies could benefit from adopting these typological insights. While a full overhaul of UD would be a massive undertaking, this research proves that the bridge between theoretical linguistics and computational parsing is structural sound—and well worth crossing.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-2897/images/cover.png)