In the rapidly evolving world of Artificial Intelligence, Large Language Models (LLMs) have become the hammer for every nail. Naturally, researchers have turned their attention to Recommender Systems (RecSys). The premise is exciting: instead of just predicting an ID for a product, why not let an LLM “generate” the recommendation, understanding user intent through natural language?

However, simply grafting an LLM onto a recommendation task isn’t plug-and-play. Most research focuses on how to train or fine-tune these models. But a new paper, “Decoding Matters: Addressing Amplification Bias and Homogeneity Issue for LLM-based Recommendation,” argues that we are overlooking a critical component: the decoding strategy.

The researchers reveal that standard decoding methods (borrowed directly from Natural Language Processing) actively sabotage recommendation quality. They introduce a novel approach called Debiasing-Diversifying Decoding (\(D^3\)) that fixes two major flaws: amplification bias and the homogeneity issue.

In this deep dive, we will explore why standard decoding fails for RecSys and unpack the \(D^3\) solution step-by-step.

The Context: Generative Recommendation

To understand the problem, we first need to understand how LLMs recommend items. In a “Generative Recommendation” setup, the model is given a prompt containing a user’s interaction history (e.g., “User liked: The Matrix, Inception…”). The model is then asked to generate the title of the next movie to watch.

The LLM generates this title token by token. To do this, it typically uses Beam Search, a decoding algorithm that explores multiple potential sequences simultaneously to find the most probable output.

In standard NLP tasks (like translation or summarization), we usually apply Length Normalization to the final scores. Why? Because the probability of a sequence is the product of the probabilities of its tokens. Since probabilities are less than 1, longer sentences naturally have lower scores. Length normalization divides the total score by the sequence length to give longer sentences a fighting chance.

\[ S(h) = S(h) / h_{L}^{\alpha} \]

This standard formula works wonders for translation. But as we are about to see, it breaks recommendation.

The Two Villains: Bias and Homogeneity

The authors identified two distinct disparities between generating natural language and generating recommendation items. These disparities lead to critical failures when using standard decoding.

1. Amplification Bias and “Ghost Tokens”

The first issue is Amplification Bias. In natural language, the vocabulary distribution is vast. But in recommendation, the model is often generating specific item titles from a constrained “item space.”

This leads to the phenomenon of Ghost Tokens. These are tokens where the generation probability is close to 1. Think of the phrase “Harry Potter and the Order of the…"—the next token “Phoenix” is almost deterministic.

In a recommender system, many items have these ghost tokens. They contribute almost nothing to the semantic “score” (since \(\log(1) \approx 0\)), but they do contribute to the length count (\(h_L\)).

Here is the trap:

- An item has many ghost tokens (it is long but predictable).

- Its raw probability score doesn’t drop much because the ghost tokens have high probability.

- However, standard length normalization divides this score by the full length.

- The result? The denominator gets bigger, but the numerator stays the same. Or, if the normalization logic attempts to boost long sequences, these items get artificially inflated scores just because they are verbose.

The authors term this Amplification Bias. The standard tool used to fix length bias in NLP actually creates a new bias in RecSys.

2. The Homogeneity Issue

The second issue is Homogeneity. LLMs are pattern-matching machines. If a user has a history of interacting with specific types of items, the LLM tends to “copy” the textual features of those items.

For example, if a user bought a “Sony PlayStation 3 Controller,” the LLM is highly likely to recommend a “Sony PlayStation 4 Controller” or “Sony PlayStation 3 Cable.” While these are relevant, they are textually repetitive. The Beam Search algorithm exacerbates this. Because similar text sequences (like PS3 vs. PS4) share many high-probability initial tokens, the “beams” all cluster around the same type of item.

The result is a recommendation list that lacks diversity. The user gets five variations of the same product rather than a diverse set of options.

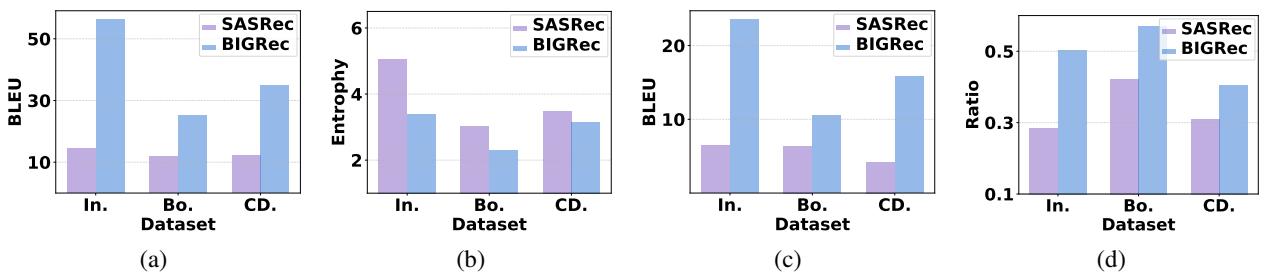

The researchers visualized this problem by comparing a standard RecSys model (SASRec) against an LLM-based model (BIGRec).

As shown in Figure 1 above:

- (a) The text similarity (BLEU score) of LLM recommendations (Blue bars) is much higher than traditional models (Purple bars).

- (b) The category diversity (Entropy) is much lower for LLMs.

- (c & d) LLMs are much more likely to repeat text and categories from the user’s history.

The Solution: Debiasing-Diversifying Decoding (\(D^3\))

To fix these issues, the authors propose a new strategy: Debiasing-Diversifying Decoding (\(D^3\)). It tackles the problems on two fronts: removing the bias and injecting diversity.

Step 1: Removing Amplification Bias (Debiasing)

The researchers initially hypothesized that they should only normalize “non-ghost” tokens. However, upon analysis, they discovered something interesting: if you ignore the ghost tokens, the “information length” of most items is actually quite uniform.

Therefore, the complex length normalization formula isn’t actually needed for recommendations if ghost tokens are the problem. The solution is elegantly simple: Remove length normalization entirely.

By disabling the normalization step (Equation 3), the model relies on the raw cumulative probability. Since ghost tokens have a probability near 1 (and log probability near 0), they naturally don’t affect the score, and they no longer distort the ranking via the length penalty.

Step 2: Fixing Homogeneity with a “Text-Free Assistant” (Diversifying)

Removing bias helps accuracy, but it doesn’t solve the “echo chamber” effect where the LLM just copies text patterns. To fix this, the authors introduce a Text-Free Assistant (TFA).

The core idea is to pair the LLM with a traditional, lightweight recommendation model (like Matrix Factorization or SASRec) that doesn’t know anything about text. This model only knows User IDs and Item IDs. It cannot be biased by similar titles because it doesn’t see titles.

The \(D^3\) method blends the scores from the LLM and the Assistant at every step of the decoding process.

First, let’s look at how the Assistant scores a token. Since the Assistant predicts items, not tokens, the authors aggregate the probability of all items that match the current token prefix:

In the equation above, \(\mathcal{L}_{TF}\) represents the score provided by the text-free model. It calculates how likely the current token sequence is to lead to a good item, based purely on collaborative filtering signals (user behavior), not text patterns.

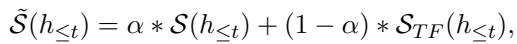

Finally, the total score used for Beam Search is a weighted sum of the LLM’s score and the Assistant’s score:

Here, \(\alpha\) is a hyperparameter that controls the balance.

- If \(\alpha = 1\), we rely solely on the LLM (high textual bias).

- As we lower \(\alpha\), we introduce more diversity from the collaborative filtering model.

This forces the LLM to consider items that are behaviorally relevant (users bought this) even if they aren’t textually similar (spelled differently).

Experiments and Results

The authors tested \(D^3\) on six real-world datasets from Amazon (Instruments, CDs, Games, Toys, Sports, Books). They compared their method against strong baselines including standard Sequential Recommendation models (SASRec) and other generative LLM methods (TIGER, BIGRec).

Accuracy Performance

The results were impressive. By simply changing how the model decodes (without retraining the massive LLM), \(D^3\) consistently outperformed the baselines.

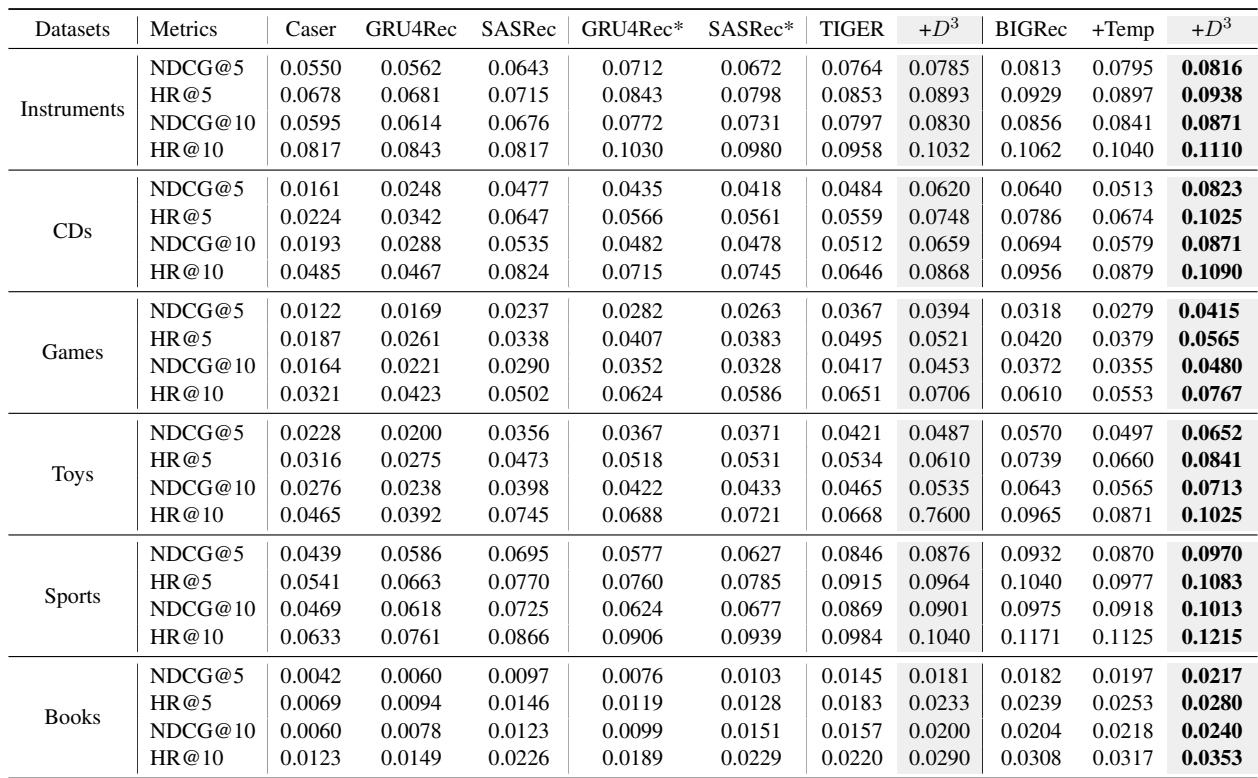

Table 1 highlights several key takeaways:

- Standard LLM performance (BIGRec) is good, but \(D^3\) is better. Across all datasets, adding \(D^3\) (the

+D3column) boosts the Hit Ratio (HR) and NDCG scores. - It works for different models. They applied \(D^3\) to TIGER (another generative model) and saw similar gains, proving the method is generalizable.

- Temperature scaling isn’t enough. The column

+Tempshows results where they tried to increase diversity just by increasing the randomness (temperature) of the LLM. While this might improve diversity, it hurts accuracy. \(D^3\) improves both.

Ablation Study: Do we need both parts?

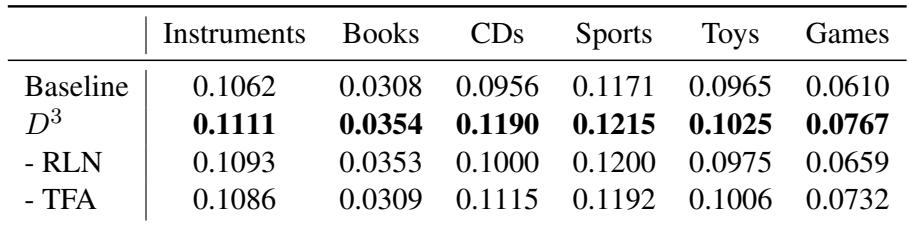

Is it enough to just remove length normalization? Or do we really need the assistant? The authors performed an ablation study to find out.

In Table 2:

- - RLN (Disabling the “Remove Length Normalization” step): Performance drops. This confirms that Amplification Bias is real and hurting the model.

- - TFA (Removing the Text-Free Assistant): Performance drops. This confirms that the collaborative signals from the assistant are crucial for guiding the LLM toward better items.

Analyzing Diversity

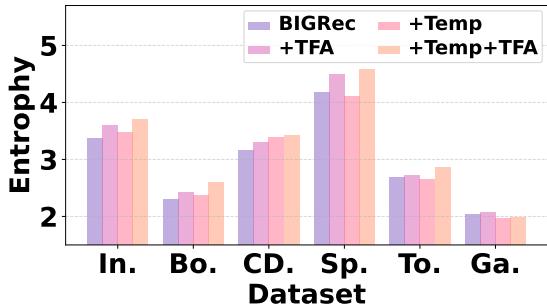

The primary goal of the Text-Free Assistant was to solve the homogeneity issue. Did it work?

Figure 2 measures diversity using Entropy (higher is better).

- Purple Bars (BIGRec): The standard model has the lowest diversity.

- Pink Bars (+TFA): Adding the Text-Free Assistant significantly boosts entropy.

- Pale Pink (+Temp+TFA): Combining the assistant with temperature scaling yields the most diverse results.

This confirms that \(D^3\) successfully breaks the “echo chamber” of text-based generation.

Beyond Accuracy: Controllable Recommendations

One of the most fascinating implications of the \(D^3\) method is the ability to “steer” recommendations. Because the decoding process mixes scores from an external model (the assistant), we can manipulate that external model to achieve specific goals.

For example, what if a platform wants to promote a specific category of items (e.g., increasing exposure for “Games” on a general store)?

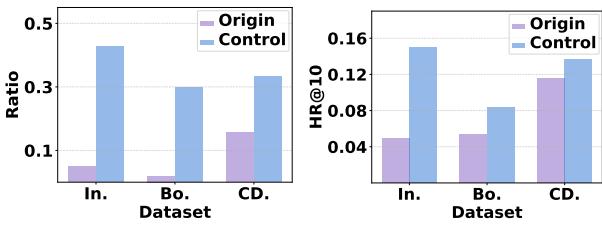

The authors ran an experiment where they biased the Assistant to favor specific categories.

Figure 3 shows the results of this control experiment.

- Left Chart (Ratio): The blue bars show a massive increase in the ratio of the target category appearing in recommendations compared to the original (purple).

- Right Chart (Accuracy): Surprisingly, forcing this distribution didn’t just flood the user with random items; the accuracy (HR@10) also increased for those categories.

This suggests that \(D^3\) could be a powerful tool for platforms that need to balance user relevance with business logic (like promoting under-exposed genres) without retraining the foundational LLM.

Conclusion

The integration of Large Language Models into recommender systems is inevitable, but this paper serves as a crucial reminder: we cannot copy-paste methodologies from NLP without scrutiny.

The generation of a movie title is fundamentally different from the generation of a sentence in a story. By identifying the mechanics of Amplification Bias (ghost tokens) and the Homogeneity Issue (textual repetition), the authors shed light on why LLMs have struggled to beat traditional baselines in some contexts.

The \(D^3\) approach offers a robust solution. By stripping away unnecessary length normalization and enlisting a “Text-Free” assistant to guide the decoding, we get the best of both worlds: the semantic understanding of an LLM and the behavioral wisdom of collaborative filtering.

For students and practitioners, the takeaway is clear: when adapting GenAI to new domains, look closely at the inference stage. Sometimes the biggest improvements come not from a bigger model, but from a smarter way of decoding the output.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-2933/images/cover.png)