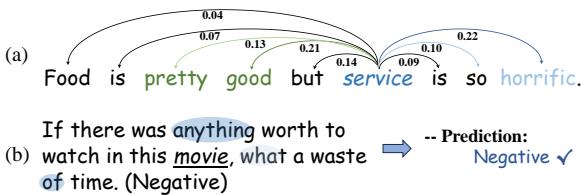

In the world of Natural Language Processing (NLP), context is everything. Consider the sentence: “The food is pretty good, but the service is so horrific.”

If you ask a standard sentiment analysis model to classify this sentence, it might get confused. Is it positive? Negative? Neutral? The reality is that it’s both—it depends entirely on what you are asking about. If you care about the food, it’s positive. If you care about the service, it’s negative.

This is the domain of Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis (ABSA). The goal is to predict the sentiment polarity (positive, negative, or neutral) of a specific aspect (like “food” or “service”) within a sentence.

For years, the industry standard for solving this has been the Attention Mechanism. Attention allows models to “look” at different parts of a sentence when making a prediction. However, recent research suggests that attention might be looking in the wrong places. It often gets distracted by irrelevant context or noisy words.

In this post, we are doing a deep dive into a paper titled “Dynamic Multi-granularity Attribution Network for Aspect-based Sentiment Analysis”. The researchers propose a shift from attention to attribution—a method that doesn’t just look at correlations, but digs into the underlying reasoning of the model to achieve state-of-the-art results.

The Problem: Attention is Not Explanation

To understand why we need a new method, we first need to understand the flaw in the current dominant approach. Most ABSA models use attention scores to decide which words are important. The theory is that if the model assigns a high attention weight to a word, that word is crucial for the prediction.

However, attention is notoriously “noisy.” It often highlights words that are syntactically related but sentimentally irrelevant.

Look at Figure 1 (a) above. The model is trying to judge the sentiment for the aspect “service.” The attention mechanism (the blue bars) assigns high scores to “pretty” and “good.” Those words describe the food, not the service. If the model relies on those attention scores, it might incorrectly predict that the service was positive.

Furthermore, as shown in Figure 1 (b), researchers have found that you can sometimes shuffle attention weights or remove “important” words without changing the prediction. This suggests that attention operates as a “black box”—it doesn’t always reflect the true reasoning process of the neural network.

The Solution: The Dynamic Multi-granularity Attribution Network (DMAN)

The authors of this paper introduce the Dynamic Multi-granularity Attribution Network (DMAN). Instead of asking “where is the model looking?” (attention), DMAN asks “which words actually caused the prediction to change?” (attribution).

This approach offers three major innovations:

- Multi-step Attribution: It uses Integrated Gradients to dynamically calculate the importance of words at different stages of understanding.

- Multi-granularity: It analyzes text at both the individual word (token) level and the phrase (span) level.

- Dynamic Syntax Concentration: It combines these attribution scores with grammatical dependency trees to filter out irrelevant sentence structures.

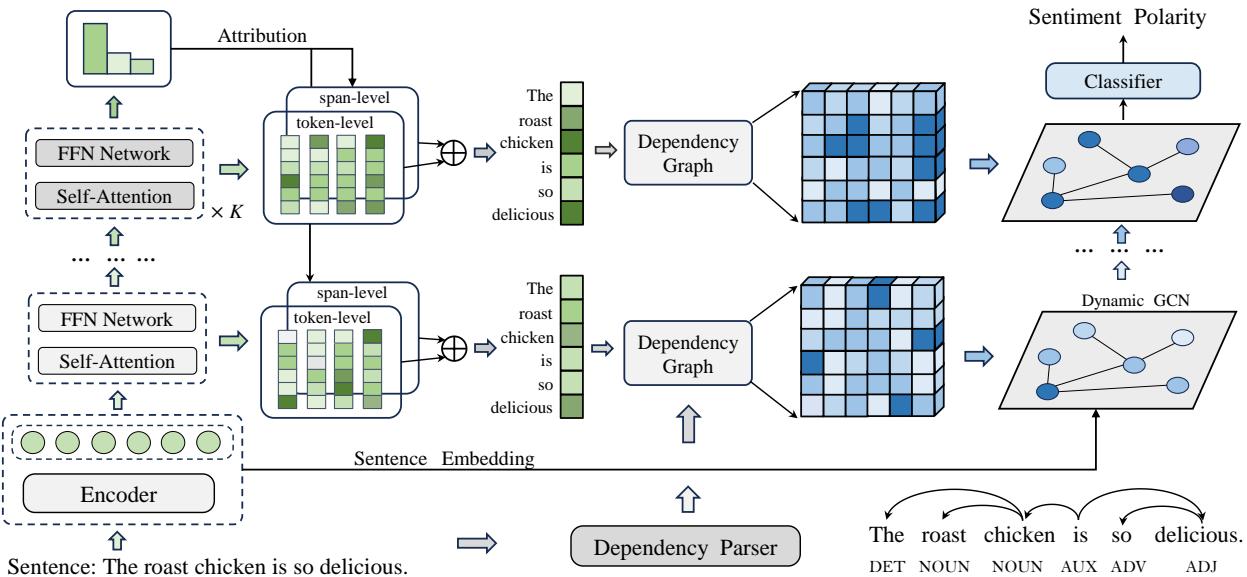

Let’s visualize the architecture before breaking it down.

As you can see in Figure 2, the model moves from a standard BERT encoder into a specialized attribution extraction process, splits into token and span levels, and finally refines the data through a Syntax-based Graph Convolutional Network (GCN).

Step 1: Multi-step Attribution Extraction

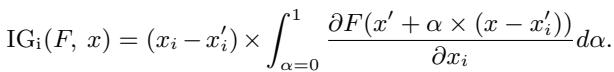

The core engine of this model is Integrated Gradients (IG).

In standard deep learning, we often look at “gradients” to see how much the output changes if we tweak an input. However, gradients can saturate (flatten out) at high values, hiding the true importance of a feature. Integrated Gradients solves this by calculating the average gradient along a path from a “baseline” (like a blank sentence) to the actual input.

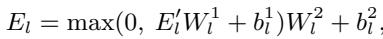

Mathematically, the Integrated Gradients for the \(i\)-th dimension are defined as:

Here, \(x\) is the input and \(x'\) is the baseline. This integral accumulates the gradients, providing a much more accurate “attribution score” that represents how much credit a specific word deserves for the final sentiment prediction.

The Stacked Architecture

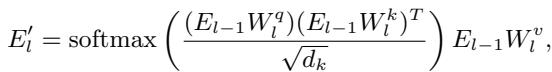

The researchers don’t just calculate this once at the end. They stack multiple blocks of Self-Attention and Feed-Forward Networks (FFN).

By calculating IG at each layer, the model captures the dynamic nature of semantic understanding. As the model reads deeper into the sentence, the importance of words shifts.

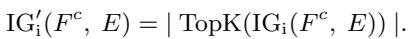

However, calculating IG for every single dimension of a vector is computationally expensive and noisy. To solve this, the authors aggregate the scores and use a Top-K strategy. They only keep the dimensions with the highest attribution values, effectively filtering out the noise that usually plagues attention mechanisms.

This results in a clean, purified signal indicating exactly which tokens are driving the sentiment analysis.

Step 2: Multi-granularity Attribution

Language is rarely processed word-by-word. We think in concepts. “New York” is a single semantic unit, not just “New” and “York.”

Existing methods often focus only on the token (word) level. DMAN introduces a Multi-granularity approach. It looks at:

- Token-level: The fine-grained details.

- Span-level: Phrases and meaningful chunks.

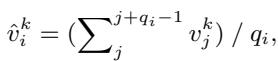

The model uses the spaCy toolkit to identify spans (phrases) in the sentence. For words that fall into the same span, the model uses mean pooling to average their attribution scores.

Ideally, we want the best of both worlds. We want the precision of tokens and the conceptual integrity of spans. The model fuses these two views using a learnable parameter \(\alpha\).

This fusion ensures the model understands that “horrific” is a powerful individual word, but “waste of time” is a powerful phrase.

Step 3: Dynamic Syntax Concentration

Knowing which words are important is step one. Step two is understanding how they relate to the aspect. This is where syntax (grammar) comes in.

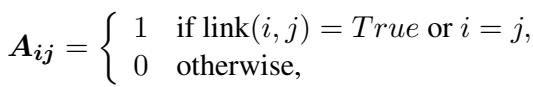

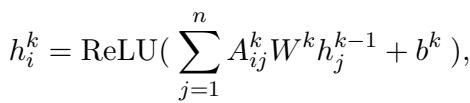

Many modern ABSA models use Dependency Trees. These are graph structures that map out the grammatical relationships between words (e.g., noun-adjective, subject-verb). The standard way to use this is via a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) over an adjacency matrix \(A\), where \(A_{ij}=1\) if two words are grammatically connected.

The Flaw in Standard Syntax

The problem with standard dependency trees is that they treat all grammatical connections as equal. In the sentence “The food is good but the service is bad,” there is a grammatical path connecting “food” to “bad” (via the conjunction “but”). A standard GCN might accidentally let the negativity of “bad” bleed over to “food.”

The Dynamic Solution

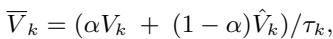

DMAN improves this by using the attribution scores (\(V_k\)) calculated in the previous steps to weight the adjacency matrix.

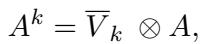

In this equation, the syntactic graph \(A\) is effectively masked by the attribution scores \(\overline{V}_k\). If a word has a low attribution score (meaning it’s irrelevant to the sentiment), its connections in the graph are suppressed.

The GCN then processes this refined graph.

This allows the model to dynamically focus on the syntactic structures that actually matter for the specific aspect being analyzed, while ignoring the grammatical noise.

Experiments and Results

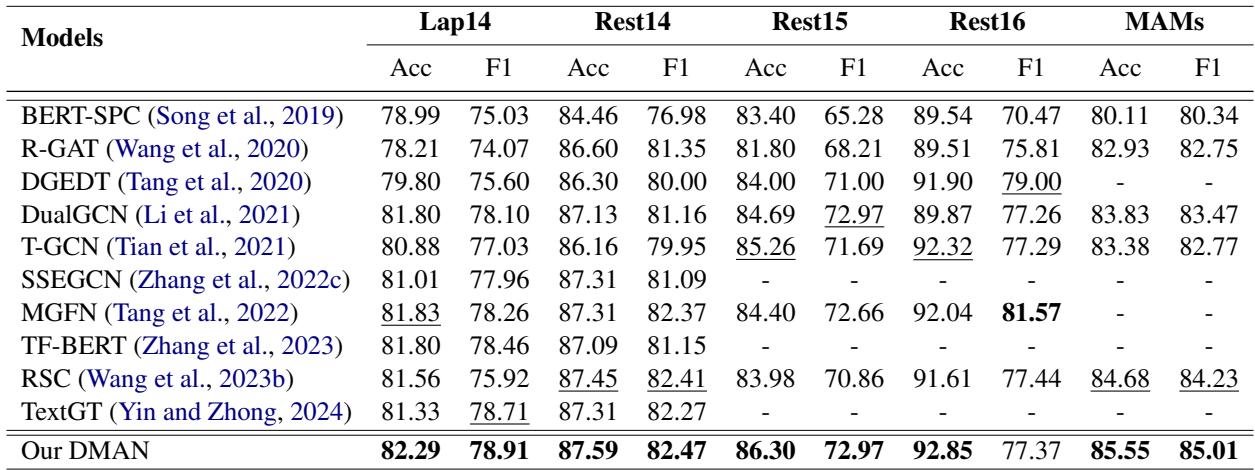

The researchers tested DMAN against five standard benchmark datasets (Laptop14, Restaurant14, Restaurant15, Restaurant16, and MAMS). They compared it against strong baselines, including BERT-SPC and various Graph-based models like DualGCN and RGAT.

Main Performance

The results were compelling. DMAN achieved state-of-the-art performance across almost all metrics.

Notice the results on the MAMS dataset. MAMS is a particularly difficult dataset designed to have multiple aspects with different sentiments in the same sentence. DMAN’s ability to outperform baselines here (85.55% Accuracy vs 83.83% for the next best) proves that the attribution mechanism successfully disentangles complex contexts.

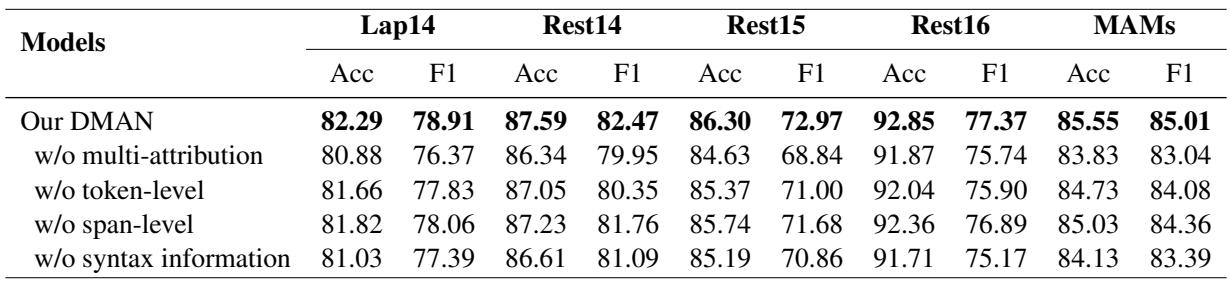

Ablation Study

To prove that each part of the model was necessary, the authors performed an ablation study, removing components one by one.

- w/o multi-attribution: Removing the attribution mechanism caused a sharp drop in accuracy (e.g., from 82.29% to 80.88% on Lap14). This confirms that standard attention is inferior to attribution.

- w/o syntax information: Removing the dependency tree integration also hurt performance, showing that grammar is still vital—it just needs to be guided by attribution.

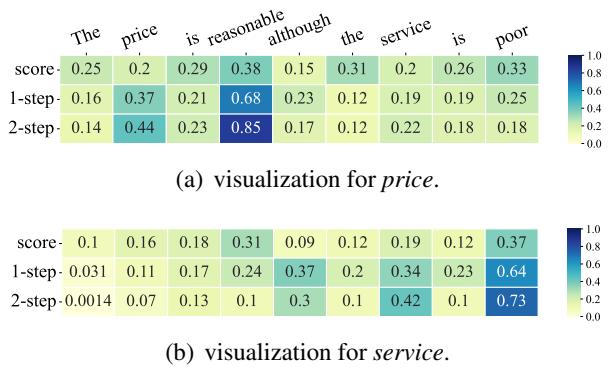

Visualizing the Improvement

The most powerful proof comes from visualizing what the model is actually “thinking.”

In Figure 6, look at the comparison between \(\alpha\) score (standard attention) and the Attribution steps.

- Aspect: Price. The standard attention (top row) looks at “poor,” which is wrong (the service is poor, not the price). The 2-step Attribution (bottom row) correctly focuses almost entirely on “reasonable.”

- Aspect: Service. The standard attention gets distracted by “reasonable.” The Attribution mechanism correctly locks onto “poor.”

This visualization confirms that DMAN is not just getting better scores by luck; it is genuinely reasoning about the sentence more like a human would.

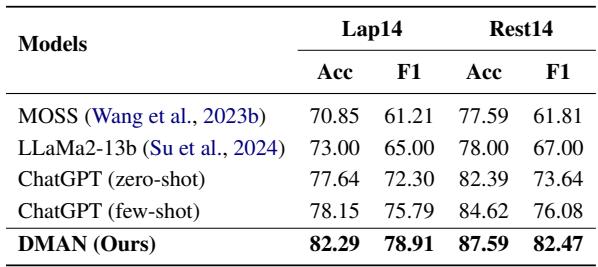

Comparison with Large Language Models (LLMs)

In the era of ChatGPT, a natural question is: “Why not just use an LLM?”

The authors compared DMAN against ChatGPT (Zero-shot and Few-shot) and LLaMa2-13b.

Surprisingly, DMAN significantly outperforms even few-shot ChatGPT on these specific tasks (87.59% vs 84.62% on Rest14). This highlights that while LLMs are powerful generalists, specialized, fine-grained architectures like DMAN are still superior for specific, high-precision tasks like ABSA.

Conclusion

The “Dynamic Multi-granularity Attribution Network” represents a significant step forward in sentiment analysis. It addresses the fundamental “black box” problem of attention mechanisms by replacing them with Integrated Gradients attribution.

By combining this attribution with multi-granularity analysis (words + phrases) and using it to refine syntactic graphs, DMAN achieves a level of precision and interpretability that previous models lacked.

For students and researchers in NLP, the key takeaway is clear: Attention is not enough. To truly understand complex sentiment, we must look deeper into the gradients and reasoning paths of our models. We need to move from merely observing correlations to understanding attributions. This paper provides a robust blueprint for how to do exactly that.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-2988/images/cover.png)