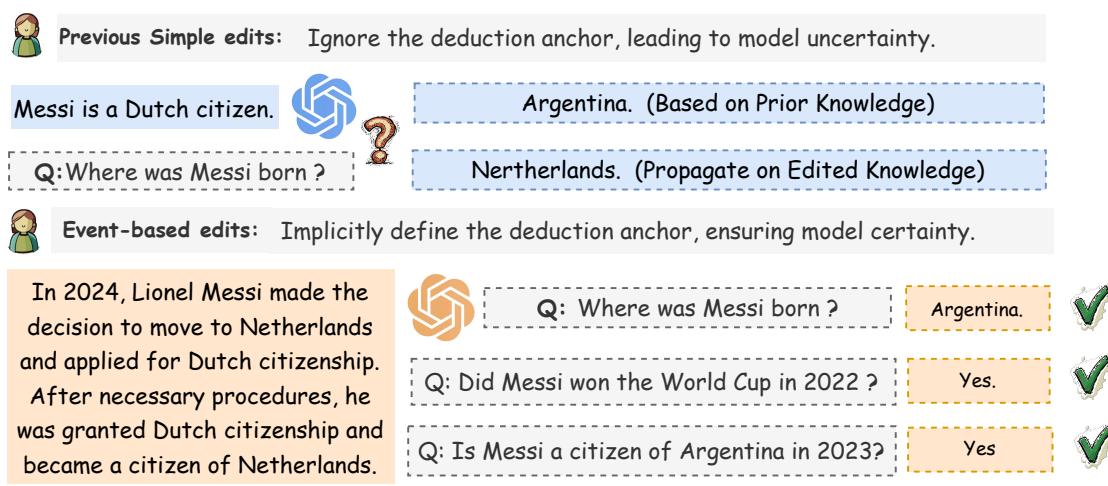

Imagine you are updating a Wikipedia page. You need to change a key fact: “Lionel Messi is now a Dutch citizen.”

If you simply update that single data point in a database, it’s fine. But Large Language Models (LLMs) aren’t databases; they are reasoning engines built on a web of correlations. If you force an LLM to believe Messi is Dutch without context, a ripple effect of confusion occurs. When you ask, “Where was Messi born?”, the model might now hallucinate “Amsterdam” because, in its statistical view of the world, Dutch citizens are usually born in the Netherlands.

This is the core problem of Knowledge Editing (KE). How do we update an LLM’s knowledge without breaking its logical reasoning?

In this post, we dive into a fascinating paper titled “EVEDIT: Event-based Knowledge Editing for Deterministic Knowledge Propagation.” The researchers argue that the current standard of editing simple facts (triples) is fundamentally flawed. They introduce a new paradigm—Event-Based Editing—and a novel method called Self-Edit that helps models update their beliefs while maintaining logical sanity.

The Problem: The “Messi Paradox” and Missing Anchors

To understand why editing LLMs is so hard, we first need to look at how we currently do it. Most state-of-the-art methods operate on triples: (Subject, Relation, Object).

For example, to update a model, we might feed it the triple: (Messi, citizen of, Netherlands).

The problem is ambiguity. When a fact changes, some related information should change, but other information should stay the same. The information that must remain true to allow for logical deduction is called the Deduction Anchor.

In the Messi example, what is the anchor?

- Possibility A: The anchor is “People are usually born in the country of their citizenship.” If the model holds onto this, updating Messi’s citizenship to Dutch implies his birthplace changes to the Netherlands. (Logical Error)

- Possibility B: The anchor is “Birthplaces are immutable facts.” If the model holds onto this, it understands that Messi can be Dutch but still be born in Argentina. (Correct Reasoning)

Current editing methods fail to define this anchor. They just shove the new fact (Messi, citizen of, Netherlands) into the weights. The result? The model gets confused.

As shown in Figure 1 above, purely triple-based editing leads to uncertainty. The model on the left, edited with a simple fact, mistakenly deduces Messi was born in the Netherlands.

However, the right side of Figure 1 shows the solution: Events. In the real world, facts don’t just magically flip. Events cause changes. If we tell the model, “In 2024, Messi applied for and was granted Dutch citizenship,” the model implicitly understands the anchor. It knows that obtaining citizenship is a process that happens after birth, so his birthplace (Argentina) remains unchanged.

The Formal Logic of Confusion

The authors of the paper didn’t just rely on intuition; they proved this mathematically. They formulated knowledge editing using formal logic.

They define the Knowledge of the Model (\(\mathcal{K}\)) as a set of propositions the model considers true.

When we edit a model, we are trying to create a new knowledge set (\(\mathcal{K}'\)). The crucial part of this process is the Deduction Anchor (\(\mathcal{K}^{\mathcal{E}}\))—the subset of existing knowledge that is assumed true during the edit.

The paper identifies two major fallacies in current research:

- No-Anchor Fallacy: Assuming we don’t need to define an anchor at all.

- Max-Anchor Fallacy: Assuming everything not directly conflicting with the edit is the anchor.

Both lead to logical contradictions. When the model encounters these contradictions, its confidence crashes.

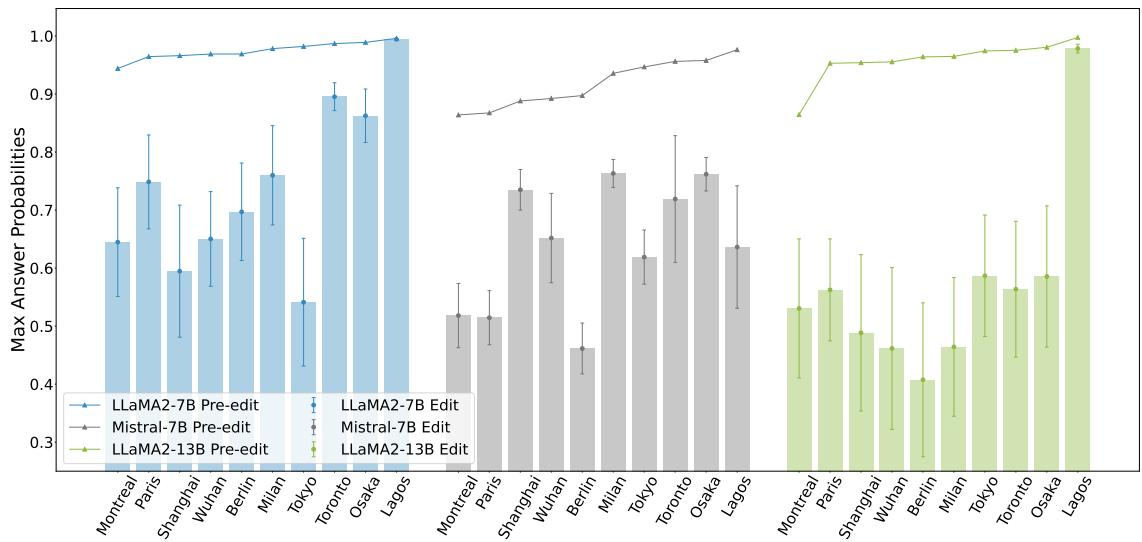

Figure 2 illustrates this crash in certainty. The chart compares “Pre-edit” confidence (the bars) with “Edit” confidence (the lines/shapes). When standard counterfactual edits (like changing a city’s country) are introduced without proper context, the model’s probability of generating the correct answer drops significantly across different model sizes (LLaMA-7B, Mistral-7B, LLaMA-13B).

The Solution: Event-Based Knowledge Editing

The researchers propose shifting the field from Triple-Based Editing to Event-Based Editing.

Instead of feeding the model (Subject, Relation, Object), we should feed it an Event Description. This is a short narrative that explains how and why the change occurred.

Why does this work? Because event descriptions contain implicit Deduction Anchors.

- Triple: “Messi is Dutch.” (Ambiguous)

- Event: “After living in Europe for years, Messi applied for Dutch citizenship in 2024.” (Clear: The “living in Europe” and “applied” context acts as the anchor).

Empirical Evidence: Events Restore Confidence

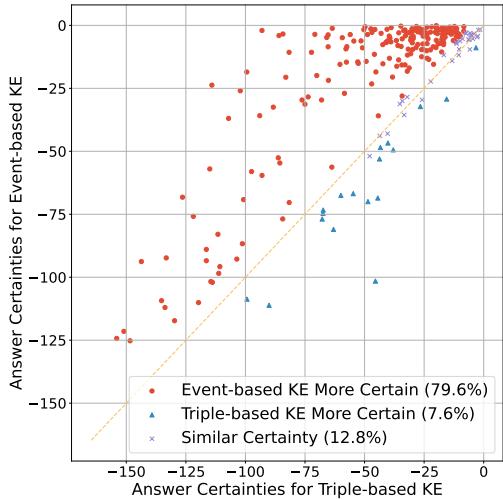

Does adding this narrative context actually help the model? The researchers conducted an experiment comparing the “certainty” (confidence) of models edited with triples versus those edited with events.

Figure 3 shows the results. Each dot represents an editing case.

- The X-axis is certainty using Triple-based editing.

- The Y-axis is certainty using Event-based editing.

- The Red Dots (which make up nearly 80% of the data) represent cases where the Event-based approach resulted in higher model confidence.

The data is clear: giving the model the “story” (the event) mitigates confusion and restores confidence in its reasoning.

The EVEDIT Benchmark

To standardize this new approach, the authors created EVEDIT. They took the popular COUNTERFACT dataset (used for testing triple edits) and upgraded it.

They used GPT-3.5 to expand the dry facts into realistic future events. They also filtered out “impossible” edits. For example, changing a historical figure’s mother tongue is impossible because they are deceased. An event-based approach respects causal logic.

Here is what a sample from the EVEDIT dataset looks like:

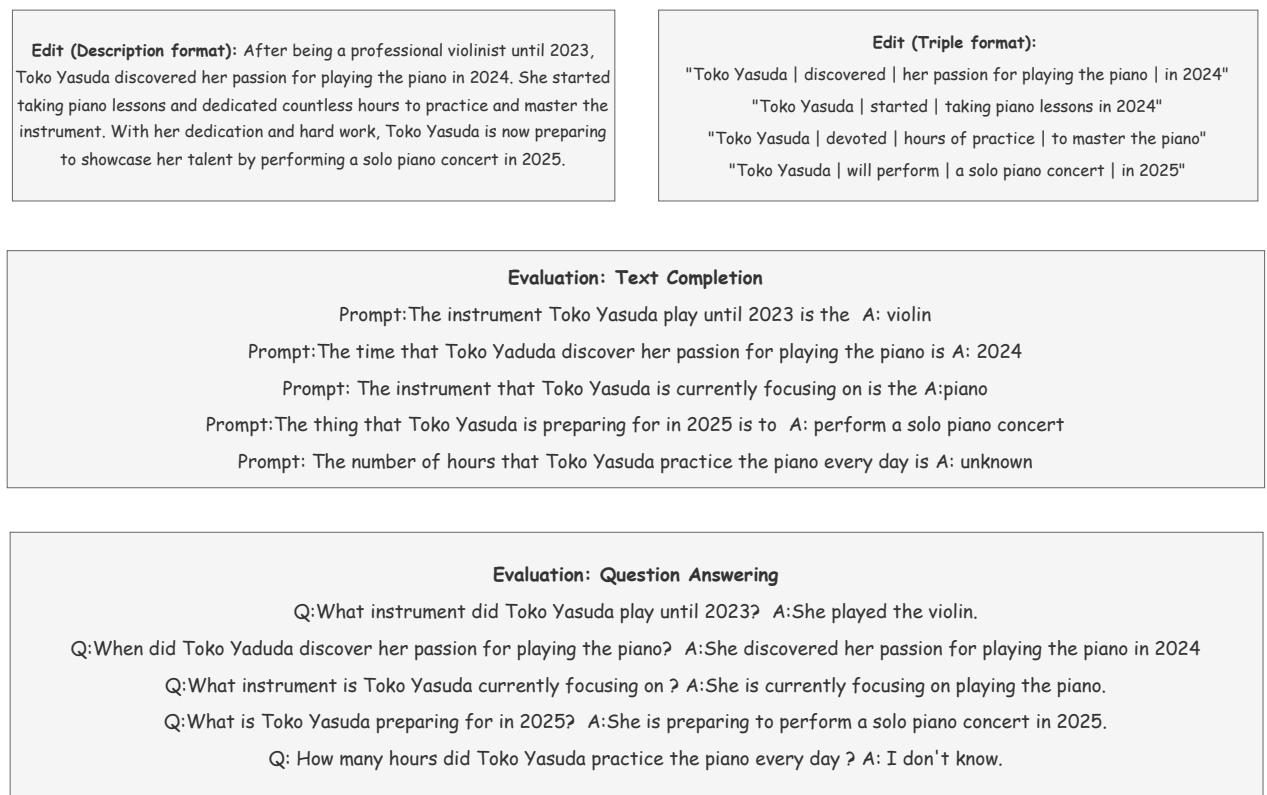

As seen in Figure 7, the dataset provides:

- The Event Description: A paragraph explaining the change (e.g., Toko Yasuda switching from violin to piano).

- Triple Decomposition: The event broken down into triples (for comparison with old methods).

- Evaluation Tasks: Both text completion and Q&A pairs to test if the model actually “understood” the change.

The Method: Self-Edit

Now that we have a better way to represent knowledge (Events), how do we actually update the model weights?

Existing methods like ROME (Rank-One Model Editing) or MEMIT (Mass-Editing Memory in a Transformer) are designed for triples. They try to locate specific neurons associated with a subject and rewrite them.

The researchers found that trying to force-fit events into these “Locate-and-Edit” methods yielded poor results. The models struggled to maintain naturalness—the generated text often became repetitive or garbled.

Instead, the authors propose a new framework: Self-Edit.

How Self-Edit Works

The logic behind Self-Edit is brilliant in its simplicity: Use the model to teach itself.

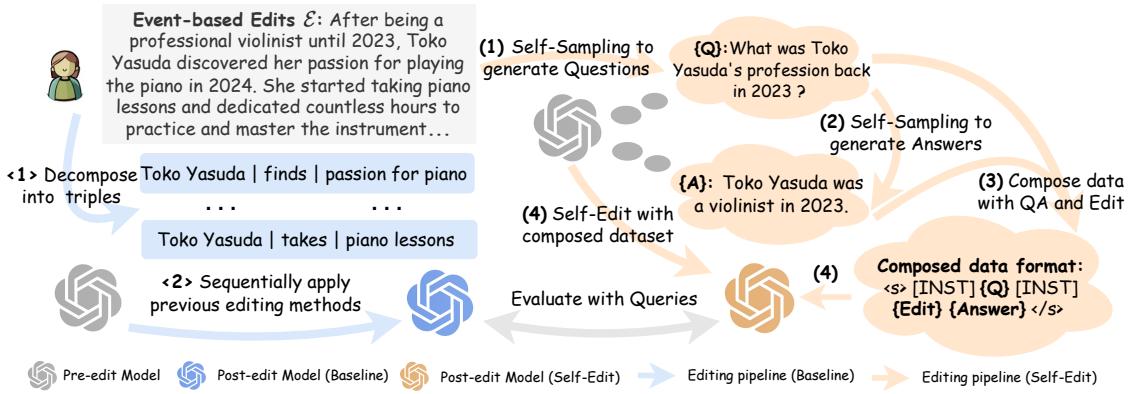

Referencing Figure 4, here is the Self-Edit pipeline (shown on the right):

- Question Generation: The model is fed the new Event Description and prompted to generate relevant Questions (\(Q\)).

- Answer Generation: The model answers its own questions (\(A\)) using the Event Description as context. Crucially, if a question cannot be answered by the event (e.g., “What did she eat for breakfast?”), the model is taught to output “I don’t know,” helping define the Editing Boundary.

- Dataset Composition: We now have a mini-dataset of

(Question, Event -> Answer)pairs. - Fine-Tuning: The model is fine-tuned on this dataset.

This approach ensures the model isn’t just memorizing a string of text. It is practicing reasoning about the new information before the weights are permanently updated.

Experiments and Results

The researchers compared Self-Edit against several baselines:

- Factual Association Methods: ROME, MEMIT, PMET (designed for triples).

- In-Context Learning (ICL): Just pasting the event into the prompt (no weight updates).

- GRACE: A method that uses a codebook of hidden states.

They measured two key metrics:

- Consistency: Did the edit stick? Can the model answer questions about it?

- Naturalness: Does the model still speak like a normal human, or did we break its language abilities?

The Results Table

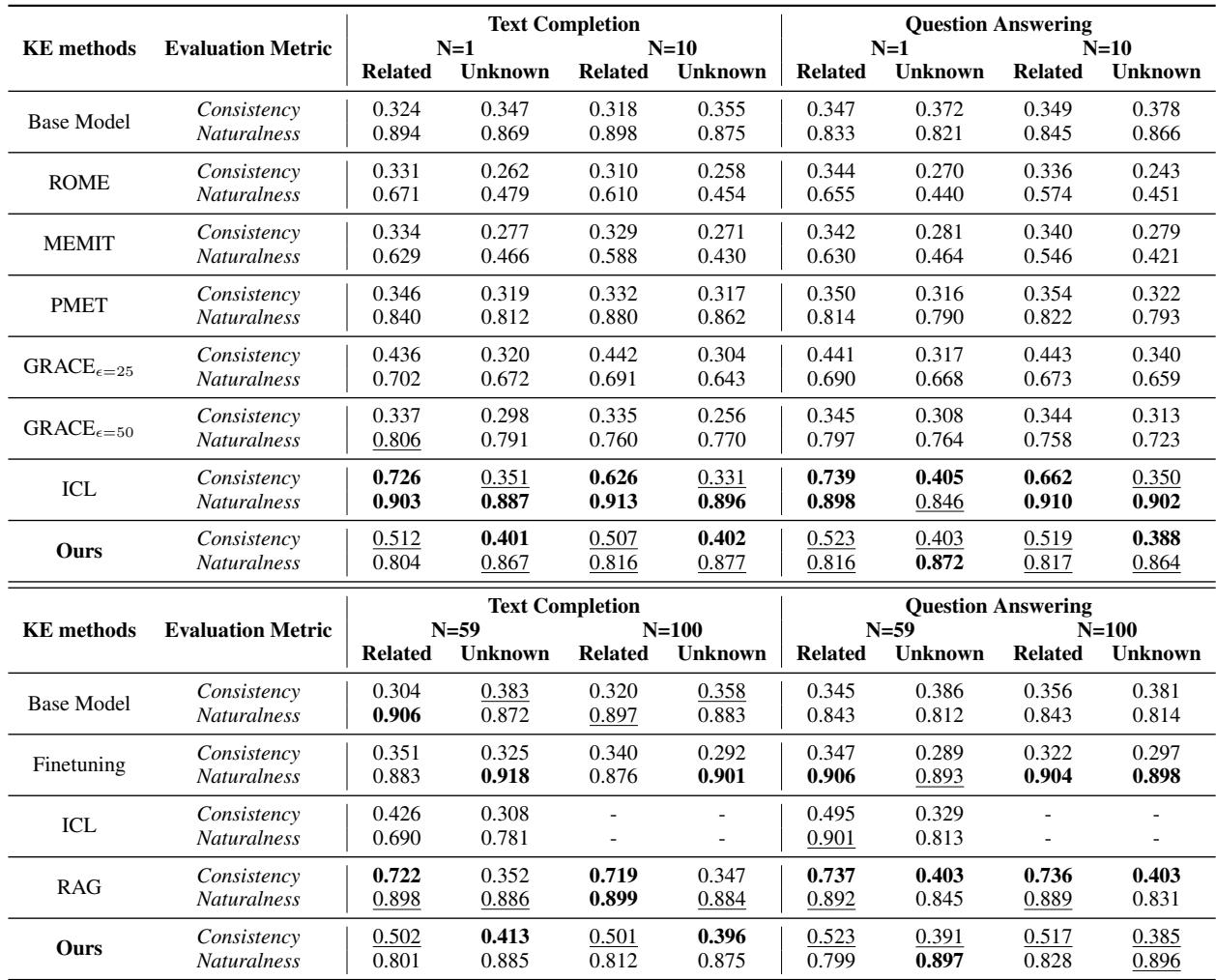

Table 1 reveals several key insights:

- Factual Association Fails: Methods like ROME and MEMIT struggled. Their “Naturalness” scores dropped significantly (e.g., ROME dropped from ~0.89 to ~0.67). This confirms that “surgery” on specific neurons is difficult when the knowledge is a complex event rather than a simple fact.

- ICL is Strong but Limited: Simply putting the event in the context window (ICL) works great (high consistency and naturalness). However, it doesn’t scale. You can’t paste 1,000 events into a prompt context window forever.

- Self-Edit Wins on Updates: Among methods that actually update the model parameters (Fine-tuning), Self-Edit achieved the best balance. It reached ~0.52 consistency (compared to ~0.34 for standard fine-tuning) while maintaining high naturalness (~0.81).

The “Unknown” Category

One of the most impressive features of the Self-Edit method is its ability to handle Unknown information.

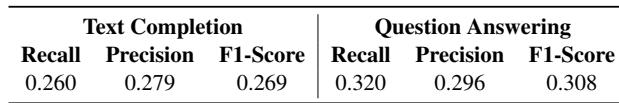

As shown in Table 2, the Self-Edit method has a specific capability to recognize the Editing Boundary. If you ask a question unrelated to the event, the model is less likely to hallucinate a false connection. While the F1-score (~0.30) shows there is still room for improvement, it is a significant step toward models that know what they don’t know.

Conclusion and Implications

The “EVEDIT” paper highlights a critical maturity step for Large Language Models. We are moving past the phase of treating LLMs like static databases where we can just “flip a bit” to change a fact.

The authors demonstrate that knowledge is interconnected. To edit a fact deterministically, we must provide the Event—the causal context that explains the change. This provides the Deduction Anchor necessary for the model to reason correctly.

Furthermore, the Self-Edit method shows that the best way to update a model isn’t necessarily invasive neuron surgery (like ROME), but rather a fine-tuning process that mimics how humans learn: by asking questions, reasoning through the new event, and integrating it into our worldview.

Key Takeaways:

- Triples are insufficient: Updating

(Subject, Relation, Object)creates ambiguity. - Events are robust: Narratives provide anchors that stabilize reasoning.

- Self-Edit works: Fine-tuning on self-generated Q&A pairs preserves the model’s fluency while ensuring the new knowledge sticks.

As we continue to integrate LLMs into dynamic real-world applications, techniques like Event-Based Editing will be essential to keep these models up-to-date without breaking their brains.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-3002/images/cover.png)