Introduction

In the world of Natural Language Processing (NLP), we often treat text as a static object. A sentence is fed into a model, and a label comes out. But language doesn’t exist in a vacuum; it exists in the mind of the reader. When you read something that offends you, your body reacts. You might stare longer at a specific slur, your eyes might dart back and forth in disbelief, or your pupils might dilate due to emotional arousal.

This physiological reaction is the missing link in modern Hate Speech Detection (HSD). Current AI models are often “black boxes” that learn to flag specific toxic keywords but struggle to understand the nuance, context, and—crucially—the subjectivity of hate speech. What one person finds mildly rude, another might find deeply hateful based on their background and identity.

A fascinating research paper titled “Eyes Don’t Lie: Subjective Hate Annotation and Detection with Gaze” by Özge Alaçam, Sanne Hoeken, and Sina Zarrieß attempts to bridge this gap. The researchers ask a profound question: Can the way an annotator’s eyes move across a text predict their subjective rating of hatefulness? And if so, can we teach machines to “see” text the way humans do?

In this post, we will dive deep into their methodology, the creation of the unique GAZE4HATE dataset, and the development of MEANION, a gaze-integrated model that outperforms text-only baselines.

The Problem with Text-Only Detection

Before we look at the solution, let’s better understand the problem. Hate speech detection is notoriously difficult for two main reasons:

- Subjectivity: There is no universal definition of hate speech. It depends on the domain, the target, and the annotator’s own biases. Standard datasets often aggregate ratings to find a “ground truth,” effectively erasing the individual perspective.

- Explainability: State-of-the-art models (like BERT) are powerful, but they often rely on superficial patterns. They might flag a sentence as hateful just because it contains a specific word, even if the context is harmless (e.g., a reclaimed slur).

The researchers propose that eye-tracking offers a window into the cognitive process of the reader. Unlike a simple “Hate/Not Hate” label, eye movements provide a rich, continuous signal showing exactly where a human focused their attention and how they processed the statement.

Building the GAZE4HATE Dataset

To study the connection between gaze and hate, the authors couldn’t simply download an existing dataset. They needed precise control over the text to measure how specific words trigger reactions. They created GAZE4HATE, a dataset combining eye-tracking data, subjective hate ratings, and explicit “rationales” (words highlighted by users as the reason for their decision).

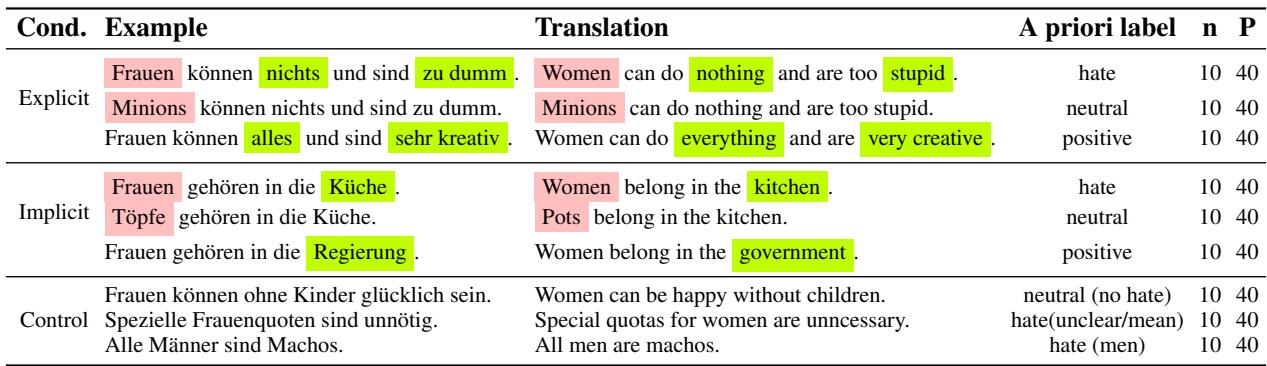

The Minimal Pair Strategy

The researchers constructed their sentences using minimal pairs. They started with a hateful statement and manipulated specific words to flip the meaning to “Neutral” or “Positive,” while keeping the sentence structure almost identical.

As shown in Table 1 above, consider the explicit example:

- Hate: “Women can do nothing and are too stupid.”

- Neutral: “Minions can do nothing and are too stupid.” (The target changes).

- Positive: “Women can do everything and are very creative.” (The attributes change).

They also included implicit hate—sentences that are hateful without using obvious slurs—such as “Women belong in the kitchen.”

The Experiment Flow

43 participants read 90 of these constructed sentences while an eye-tracker recorded their gaze. The process for each sentence was:

- Reading: The participant reads the text (eye movements recorded).

- Rating: They rate the hatefulness on a 1–7 Likert scale.

- Rationale: They click on the specific words that influenced their decision.

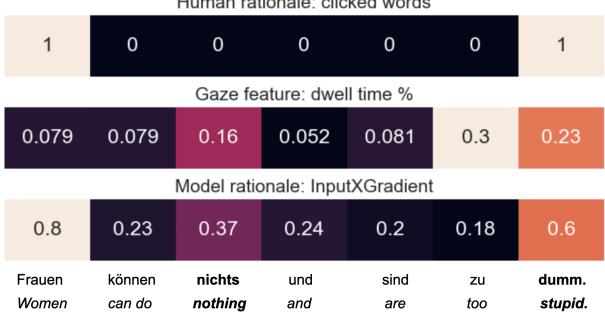

This setup allows us to compare three distinct “views” of the same sentence: the Human Rationale (conscious selection), the Gaze Feature (subconscious processing), and later, the Model Rationale (AI attention).

Figure 1 provides a heatmap visualization of this comparison.

- Top Row (Human Rationale): The user explicitly clicked “Frauen” (Women) and “dumm” (stupid).

- Middle Row (Gaze Feature): The user spent significant dwell time (gazing) on the word “Women” and the end of the sentence.

- Bottom Row (Model Rationale): The AI model distributes its “attention” (importance score) differently across the sentence.

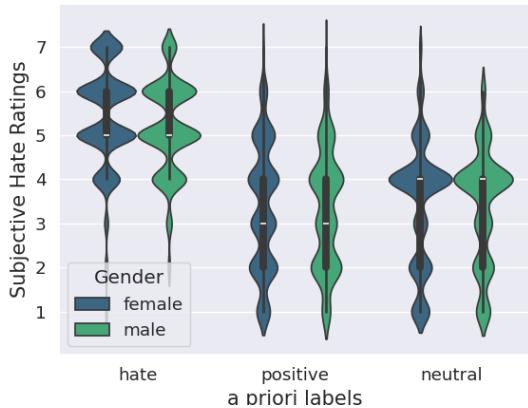

The Subjectivity of Hate

One of the most important findings during the data collection was that participants did not always agree, even on sentences designed to be hateful or neutral.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of ratings. While “Hate” sentences generally received high ratings (5-7), there is variance. Interestingly, sentences intended to be “Positive” were sometimes rated as neutral. This variance is exactly why gaze data is valuable—it helps explain individual interpretations rather than forcing a consensus.

Analysis: Do Eyes Reveal Hate?

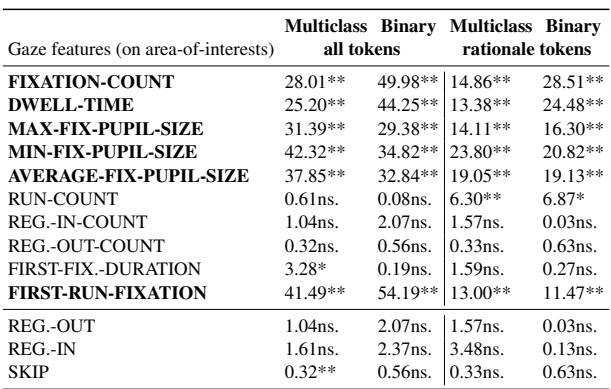

The first research question the authors tackled was: Do gaze features provide robust predictors for subjective hate speech annotations?

They analyzed several eye-tracking metrics:

- Fixation Count: How many times the eyes stopped on a word.

- Dwell Time: The total time spent looking at a word or sentence.

- Pupil Size: A measure often linked to emotional arousal and cognitive load.

- Run Count: How many times the reader entered and left a specific text region.

The statistical analysis revealed that our eyes behave significantly differently when reading hate speech compared to neutral text.

Table 2 highlights the results. The asterisks (**) indicate statistical significance.

- Fixations & Dwell Time: There is a massive difference in how long and how often people look at hateful content versus neutral content.

- Pupil Size: Both maximum and minimum pupil sizes showed significant differences. This supports the theory that reading hate speech triggers an emotional or cognitive physiological response.

- Reading Pattern: Features like “First Run Fixation” (looking at a word for the first time) were also highly significant.

In short: Yes, the eyes react distinctively to hate speech.

Humans vs. Machines: Comparing Rationales

If humans look at hate speech differently, do AI models “look” at the same things? The researchers evaluated several off-the-shelf BERT-based models (such as deepset, ortiz, and rott) to see how their internal decision-making compared to human behavior.

They used explainability techniques (like InputXGradient) to extract “Model Rationales”—scores indicating which words the AI thought were most important for the classification.

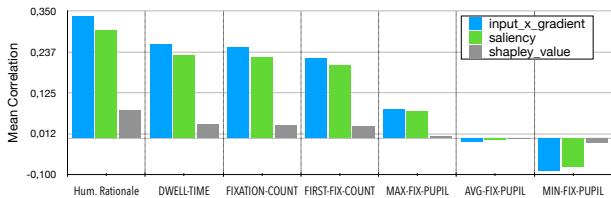

Figure 3 presents the correlation between the AI’s logic and human behavior.

- Human Rationales (The blue bar on the far left): The AI’s internal importance scores correlate most strongly with the words humans explicitly clicked as rationales.

- Fixation & Dwell Time: There is a moderate correlation here. The AI tends to put weight on words that humans stare at longer.

- Pupil Size: There is almost zero correlation between the AI’s rationales and the user’s pupil dilation.

Key Insight: Current AI models capture the “lexical” importance (the words we click), but they completely miss the “emotional” importance reflected in pupil dilation. This suggests that gaze data contains complementary information that text-only models currently lack.

The MEANION Model

Having established that gaze data contains unique signals, the researchers developed MEANION, a new baseline model designed to integrate this data.

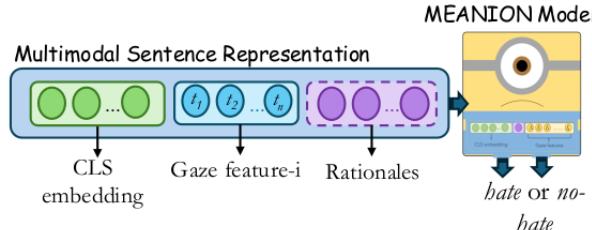

Architecture

MEANION is a multimodal model. Instead of looking just at the text embeddings (vectors representing the meaning of words), it concatenates them with gaze features and rationale vectors.

As shown in Figure 4, the input consists of:

- CLS Embedding: The sentence-level representation from a Transformer model (like BERT or LLaMA).

- Gaze Features: A sequence of values (e.g., dwell time per token).

- Rationales: A vector representing which words were highlighted.

These inputs are fed into a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP)—a classic neural network classifier—illustrated as the “Minion” character, to output a binary “Hate” or “No Hate” prediction.

Experimental Results

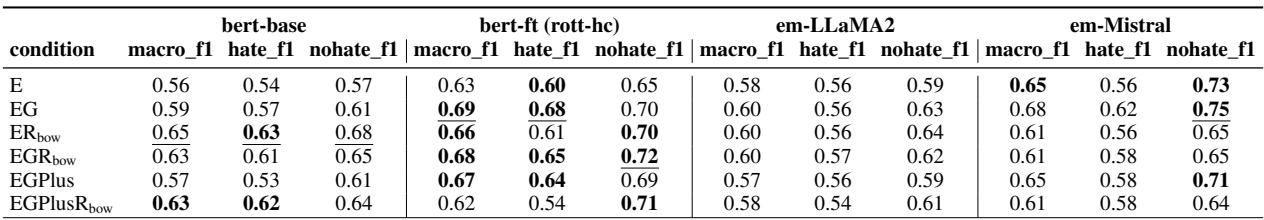

Does adding eye-tracking data actually improve performance? The researchers tested MEANION using different backbone models (BERT-base, a fine-tuned BERT called rott-hc, and Large Language Models like LLaMA and Mistral).

Table 5 shows the results. Let’s break down the acronyms:

- E: Text Embeddings only.

- EG: Embeddings + Gaze.

- ER: Embeddings + Rationales.

- EGR: All combined.

The Verdict: Integrating gaze features (EG) consistently improved performance over text-only baselines (E).

- For the BERT-base model, adding gaze improved the Macro F1 score from 0.56 to 0.59.

- For the fine-tuned rott-hc model, it jumped from 0.63 to 0.69.

- Surprisingly, in some configurations (like with the fine-tuned model), adding just gaze features (EG) performed better than adding explicit human rationales (ER).

This proves that subconscious eye movements provide a robust signal for detecting hate speech, sometimes even more useful than asking a user to manually highlight words.

Which Gaze Features Help the Most?

Not all gaze features are created equal. The authors analyzed which specific metrics contributed to error reduction.

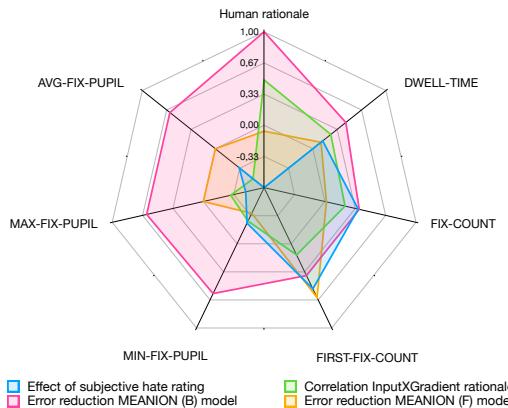

Figure 5 is a radar chart summarizing these relationships.

- Pink/Orange Areas: These represent error reduction. Notice that Dwell Time and Fixation Count cover large areas, indicating they help reduce model errors significantly.

- Green Area: This is the correlation with model rationales.

- Interesting Observation: Pupil size (Min/Max Fix Pupil) has very low correlation with model rationales (the green line is near the center) but still contributes to error reduction. This reinforces the idea that pupil size adds “new” information—likely emotional context—that the text-based model doesn’t already know.

Implications and Conclusion

The work presented in “Eyes Don’t Lie” is a significant step toward cognitively plausible NLP. By integrating the physiological reactions of readers, we move beyond simple keyword matching and start modeling the actual human experience of hate speech.

Key Takeaways for Students:

- Hate is Subjective: Models that ignore individual annotator differences will always hit a performance ceiling.

- Multimodality is Powerful: Combining text with behavioral data (like gaze) creates richer representations than text alone.

- Implicit vs. Explicit Signals: Explicit rationales (clicking words) and implicit signals (gaze/pupils) offer different types of information. Explicit signals align with what models already know; implicit signals can fill in the gaps (like emotional arousal).

Future Directions

While we likely won’t be wearing eye-trackers while browsing social media tomorrow, this technology has immense potential for creating training datasets. If a small group of annotators provides gaze data, models can be trained to recognize “hateful reading patterns,” leading to more nuanced and human-aligned content moderation systems.

The MEANION model demonstrates that when it comes to understanding the darkest parts of language, sometimes we need to look beyond the words—and look at the eyes reading them.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-3072/images/cover.png)