Introduction: The Heavy Lift of Fine-Tuning

We are living in the golden age of Large Language Models (LLMs). From LLaMA to GPT-J, these models have demonstrated incredible generative capabilities. However, there is a massive catch: size. With parameter counts soaring into the billions, fine-tuning these behemoths for specific downstream tasks—like mathematical reasoning or specialized Q&A—requires computational resources that are out of reach for many researchers and students.

To solve this, the community turned to Parameter Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT). Methods like LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) and Prefix Tuning freeze the massive pre-trained model and only train a tiny sliver of new parameters. These techniques have been game-changers.

But recently, researchers from the Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications asked a provocative question: Are we treating all layers of these massive neural networks too equally?

Most current PEFT methods apply the same strategy uniformly across every layer of the Transformer. Yet, we know from interpretability research that different layers play different roles. Bottom layers handle syntax and specific details; top layers handle abstract semantics.

In this post, we will dive deep into a paper titled “From Bottom to Top: Extending the Potential of Parameter Efficient Fine-Tuning”. We will explore how the authors developed two new methods, HLPT and H\(^2\)LPT, which assign different fine-tuning strategies to different layers. Most surprisingly, we will discover how they managed to achieve state-of-the-art results by ignoring the middle half of the neural network entirely, cutting trainable parameters by over 70%.

Background: Not All Layers Are Created Equal

Before we get into the new architecture, we need to understand the “ingredients” used in this recipe: LoRA and Prefix Tuning, and the intuition regarding Transformer layers.

The Ingredients

- LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation): This method injects trainable low-rank matrices into the model. It essentially modifies the model’s weights directly but in a very efficient way. Because it tweaks weights, it is excellent at adjusting specific information retention.

- Prefix Tuning: This method prepends learnable “virtual tokens” to the input of the attention mechanism. It’s like whispering a prompt to the model to steer its behavior. It acts more like context, making it suitable for guiding abstract generation.

The Layer Intuition

Previous research (BERTology, etc.) has suggested a hierarchy in how Transformers process language:

- Bottom Layers: Focus on sentence-level information, syntax, and specific details.

- Middle Layers: Capture syntactic interactions.

- Top Layers: Store abstract semantic information and handle high-level reasoning.

The authors hypothesized that applying the same fine-tuning method (like just LoRA or just Prefix) to every single layer ignores this natural hierarchy.

The Investigation: Does Placement Matter?

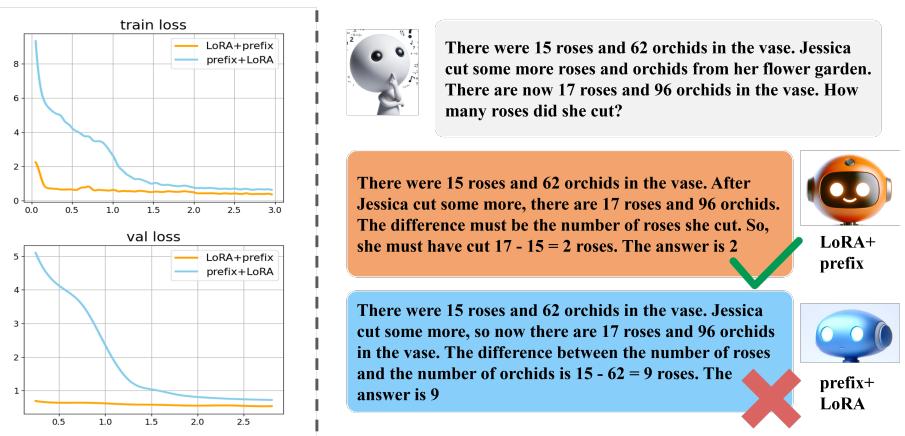

To test their hypothesis, the researchers conducted a fascinating preliminary experiment using LLaMA-7B. They split the model into two halves: the bottom layers and the top layers. They then tested two configurations:

- LoRA + Prefix: LoRA applied to the bottom layers, Prefix Tuning applied to the top.

- Prefix + LoRA: Prefix Tuning applied to the bottom, LoRA applied to the top.

The results were stark.

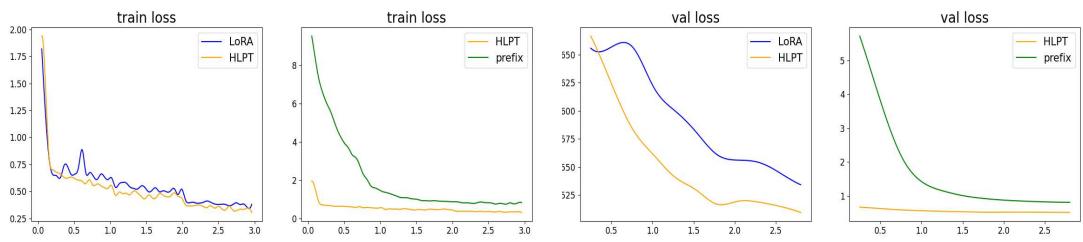

As shown in Figure 1 above, the arrangement matters immensely.

- Left (Loss): The “Prefix+LoRA” setup (blue line) struggled to converge effectively. The “LoRA+Prefix” setup (orange line) converged smoothly and quickly.

- Right (Generation): When asked a simple math word problem, the model with Prefix at the bottom and LoRA at the top failed completely (hallucinating numbers). The model with LoRA at the bottom and Prefix at the top answered correctly.

The takeaway? LoRA is better suited for the “specifics” at the bottom, while Prefix Tuning helps steer the “abstracts” at the top.

Finding the Golden Ratio

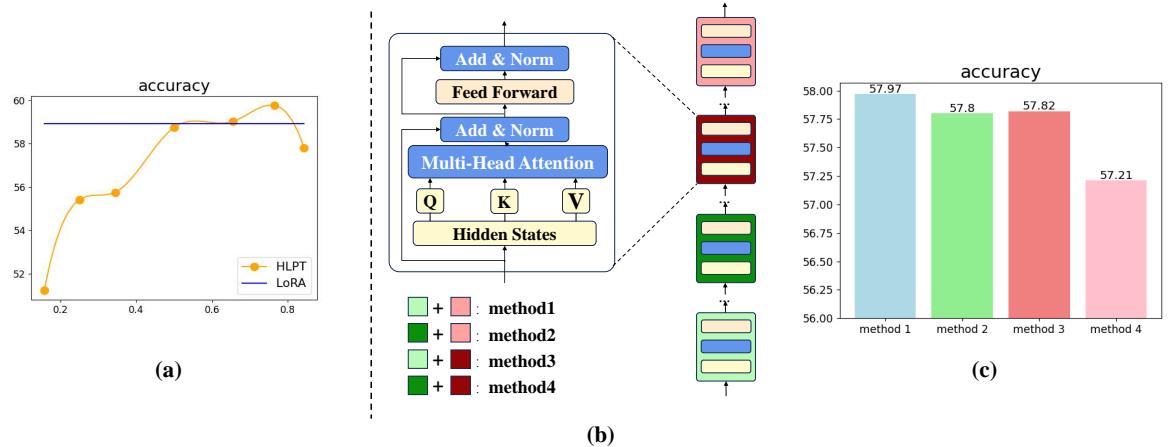

Once they established that “LoRA Bottom / Prefix Top” was the winning combination, they needed to find the optimal ratio. How many layers should be LoRA, and how many should be Prefix?

In Figure 2(a), the orange line tracks accuracy as they shift the ratio. They found that a split of roughly 3:1 (applying LoRA to the bottom 3/4 of layers and Prefix to the top 1/4) yielded the best performance.

The “Half” Hypothesis

Here is where the paper gets truly interesting. The researchers noticed that fine-tuning every layer might be redundant. If the middle layers are just passing information between the syntactic bottom and the semantic top, do we need to fine-tune them at all?

They tested four methods of reducing parameters (shown in Figure 2(b)), and the results in Figure 2(c) confirmed it: You can skip fine-tuning the middle layers without significant performance loss. In fact, doing so can sometimes improve results by preventing overfitting or noise in those transitional layers.

The Core Method: HLPT and H\(^2\)LPT

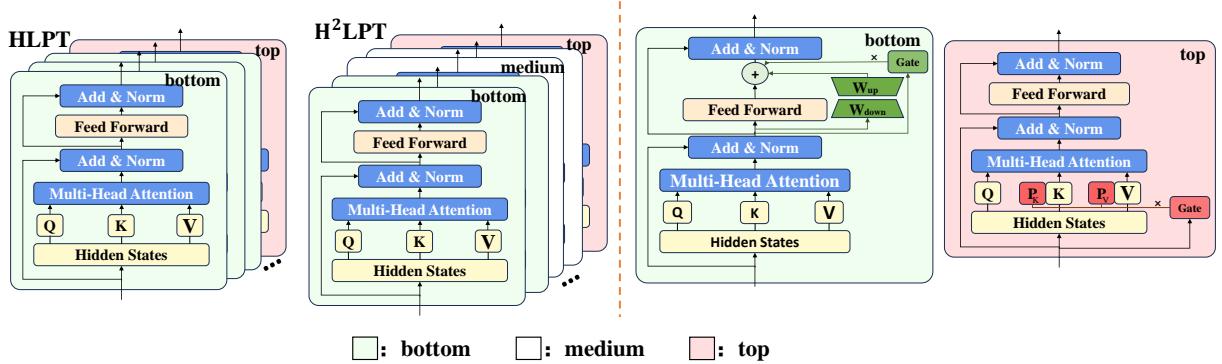

Based on these insights, the authors propose two distinct architectures.

1. HLPT (Hybrid LoRA-Prefix Tuning)

This method applies LoRA to the bottom layers (specifically targeting the Feed-Forward Networks) and Prefix Tuning to the top layers (targeting the Attention mechanism). This aligns the fine-tuning method with the information type stored in those layers.

2. H\(^2\)LPT (Half Hybrid LoRA-Prefix Tuning)

This is the more aggressive and efficient version. It takes the HLPT architecture but completely ignores the middle layers. It only fine-tunes the bottom-most and top-most blocks.

Figure 3 illustrates the difference:

- Left (HLPT): The green blocks (LoRA) cover the bottom, and pink blocks (Prefix) cover the top.

- Right (H\(^2\)LPT): We see a massive “white space” in the middle. These layers are frozen and untouched. This drastically reduces the number of trainable parameters.

Under the Hood: The Mathematics

Let’s look at the mathematical implementation. The authors didn’t just slap standard LoRA and Prefix on; they enhanced them with a Gating Mechanism.

The Basics

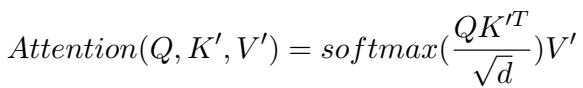

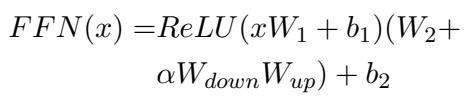

First, recall the standard Attention and Feed-Forward Network (FFN) calculations in a Transformer:

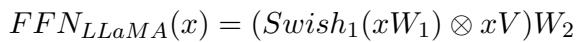

For LLaMA specifically, the FFN is slightly different (using Swish activations):

Adaptive Prefix Tuning (Top Layers)

For the top layers, the authors use Prefix Tuning. They add virtual tokens (\(P_k, P_v\)) to the Keys and Values.

However, they introduce a Gating Unit (\(g_p\)). Instead of adding static prefixes, the model computes a value between 0 and 1 based on the input \(x\). This gate scales the prefix vectors, allowing the model to dynamically decide how much the prompt should influence the current token generation.

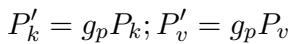

Adaptive LoRA (Bottom Layers)

For the bottom layers, they apply LoRA. Standard LoRA usually targets the Attention mechanism (\(W_Q, W_V\)). However, to further differentiate the roles (since they use Prefix on Attention at the top), the authors apply LoRA to the Feed-Forward Network (FFN) at the bottom.

Standard LoRA update rule:

Applying this to the FFN weight \(W_2\):

And specifically for the LLaMA architecture:

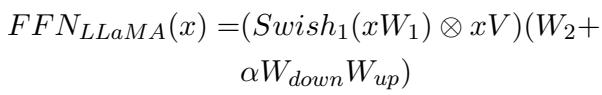

Just like the Prefix layers, the LoRA layers also get a Gating Unit (\(g_l\)). This allows the model to dynamically scale the influence of the LoRA weights (\(\alpha\)) based on the input features of the FFN (\(h_{FN}\)).

This adaptive gating mechanism is a crucial addition. It means the fine-tuning isn’t a “hard” overwrite of the model’s behavior; it’s a context-aware modulation.

Experiments and Results

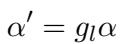

To validate these methods, the authors tested them on rigorous mathematical reasoning datasets (like GSM8K, SVAMP, and AQuA) using LLaMA-7B, LLaMA-13B, and GPT-J. These tasks require strict logic, making them excellent benchmarks for generation capabilities.

Main Performance

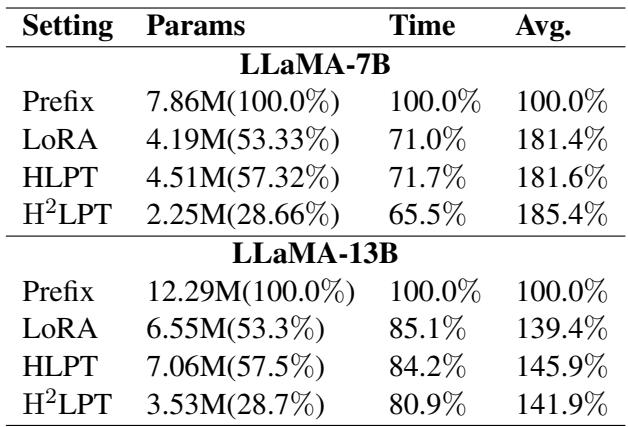

The results were impressive. Let’s look at Table 1.

Key Takeaways from Table 1:

- HLPT vs. Baselines: HLPT (Hybrid) consistently outperforms standard Prefix and LoRA tuning across almost all datasets. For example, on SVAMP with LLaMA-7B, HLPT scores 60.50 compared to LoRA’s 56.00.

- The Power of H\(^2\)LPT: Look at the row for H\(^2\)LPT. Even though it fine-tunes significantly fewer layers (ignoring the middle), it remains competitive with, and often beats, the full HLPT and standard LoRA models.

- Scaling: The advantage holds up on the larger LLaMA-13B model, where HLPT achieves the highest average score of 68.27.

Robustness and Efficiency

One of the most compelling arguments for this method is how it behaves during training.

Figure 4 compares the training loss (left) and validation loss (right).

- Blue line (LoRA): Notice the volatility. The loss jumps around, indicating unstable training.

- Orange line (HLPT): The curve is incredibly smooth. The hybrid approach, combined with the gating mechanism, leads to much more stable convergence.

Furthermore, the parameter efficiency is drastic.

(Note: While the full table isn’t shown in the deck, the text summarizes these findings). H\(^2\)LPT reduces the parameter count by nearly 50% compared to standard LoRA and HLPT, yet achieves comparable or better accuracy. This translates to lower storage costs and slightly faster training times.

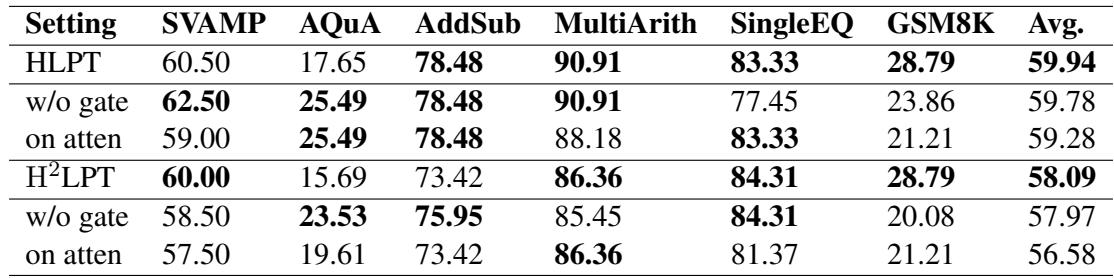

Ablation Studies: Do we really need the gates?

You might ask, “Is it the layer splitting that helps, or just those fancy gating mechanisms?” The authors performed ablation studies to find out.

Table 3 shows what happens if you remove components:

- w/o gate: Removing the gating mechanism drops performance (Avg 59.94 -> 59.78 for HLPT). The gates help, but they aren’t the only reason for success.

- on atten: Moving LoRA back to the Attention layers (instead of FFN) also hurts performance. This confirms that separating the “locations” (LoRA on FFN, Prefix on Attention) is beneficial.

Conclusion: Less is More

The paper “From Bottom to Top” provides a fresh perspective on how we approach Large Language Models. Instead of treating the model as a monolith where every layer is equal, the authors demonstrate that respecting the hierarchy of information—syntax at the bottom, semantics at the top—unlocks better performance.

The introduction of H\(^2\)LPT is perhaps the most exciting contribution for students and researchers with limited hardware. It proves that we can effectively “turn off” fine-tuning for the middle half of a massive model and still achieve state-of-the-art results on complex reasoning tasks.

Key Takeaways:

- Split Strategies: Use LoRA for bottom layers (details) and Prefix Tuning for top layers (abstraction).

- Target Components: Apply LoRA to FFNs and Prefix to Attention for maximum separation of concerns.

- Skip the Middle: The middle layers of a Transformer are often redundant for fine-tuning. Skipping them saves massive amounts of memory without hurting accuracy.

- Adaptive Gating: Letting the model decide when to use the fine-tuned parameters stabilizes training.

As models continue to grow, smart, surgically precise methods like H\(^2\)LPT will be essential for keeping AI accessible and efficient.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-3113/images/cover.png)