Introduction

Imagine a lawyer walking into a courtroom, confident in their case, only to be sanctioned by the judge because the legal precedents they cited didn’t exist. Or consider a company’s stock value dropping by $100 billion because their AI demo claimed the James Webb Space Telescope took the first picture of an exoplanet (it didn’t).

These aren’t hypothetical scenarios; they are real-world consequences of Large Language Model (LLM) hallucinations. As LLMs become integrated into search engines, customer service bots, and professional workflows, the cost of “making things up” becomes increasingly high.

The problem is that detecting these errors automatically is incredibly difficult. A simple keyword check isn’t enough because an AI can say something factually wrong using grammatically perfect and plausible-sounding language.

In this post, we are diving deep into HalluMeasure, a new research framework proposed by researchers at Amazon. This paper introduces a sophisticated pipeline that doesn’t just ask “Is this true?” but breaks down AI responses into atomic claims and uses Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning to evaluate them. We will explore how this method works, why “showing your work” helps AI catch other AI’s lies, and how it performs against current state-of-the-art detection tools.

The Challenge of Automated Detection

To understand why HalluMeasure is necessary, we first need to look at how we currently evaluate AI factuality.

Traditionally, measuring hallucinations often involved checking the similarity between the generated text and a reference document using metrics like N-gram overlap (ROUGE scores) or embedding similarity (BERTScore). However, these metrics measure similarity, not factuality. A summary can use different words than the source text and be true, or use similar words and be false.

More recent approaches use “Natural Language Inference” (NLI) models to classify a sentence as “entailed” (supported), “contradicted,” or “neutral.” While better, these often operate at the sentence level. A single sentence from an LLM might contain three different facts: two might be true, and one might be a hallucination. If you evaluate the whole sentence at once, you lose precision.

HalluMeasure tackles these issues by introducing two major shifts in strategy:

- Fine-grained Claim Extraction: Breaking responses down into the smallest possible units of information.

- Chain-of-Thought Verification: Using an LLM to reason through the evidence before assigning a label.

The HalluMeasure Architecture

The core logic of HalluMeasure is a multi-step pipeline. Instead of a “black box” that outputs a score, the system mimics how a human fact-checker works: identifying claims, checking the source, and reasoning about the validity of each claim.

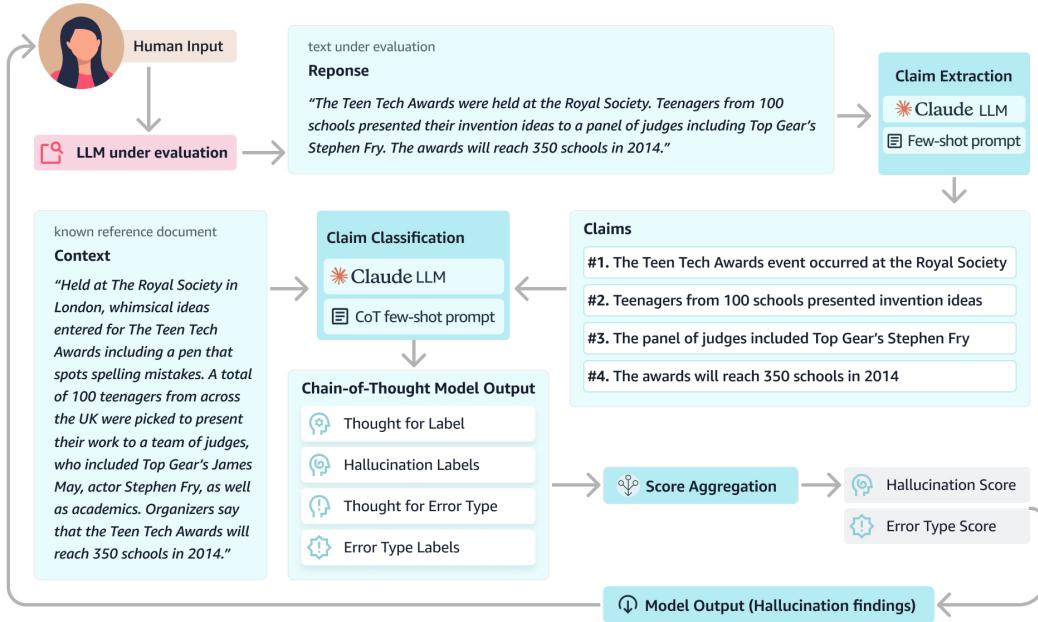

As shown in Figure 1, the process consists of three main phases:

- Claim Extraction: An LLM decomposes the response into a list of atomic claims.

- Classification: Another LLM (the classifier) compares each claim against the reference context.

- Aggregation: The system calculates a final hallucination score based on how many claims failed the check.

Step 1: Atomic Claim Extraction

The first step is critical. If an LLM generates a complex sentence like, “Samsung’s Gear Blink could have a projected keyboard that allows you to type in the air,” a standard evaluator might struggle to pinpoint an error if the product name is right but the feature is wrong.

HalluMeasure passes the response to an extraction model (built on Claude 2.1) which breaks that sentence down into atomic claims:

- Samsung has a product called Gear Blink.

- Gear Blink could have a projected keyboard.

- Gear Blink’s projected keyboard would allow typing in air.

By isolating these facts, the system can mark the first claim as “True” and the second as “Hallucinated” if the context doesn’t support it. This granularity prevents a single small error from invalidating an otherwise correct paragraph, while also preventing a mostly correct paragraph from hiding a dangerous lie.

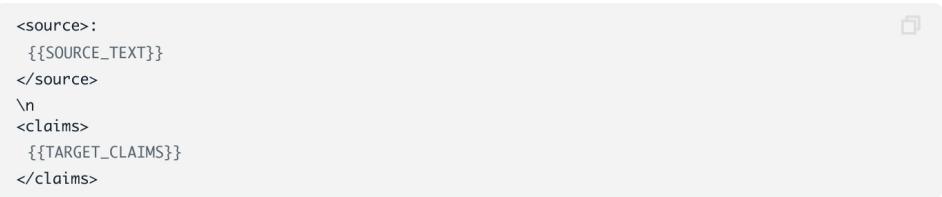

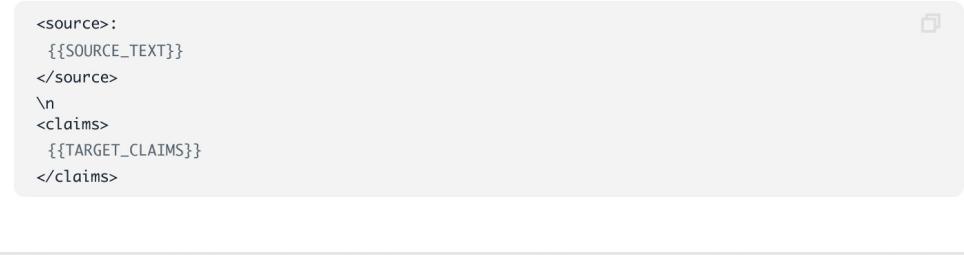

The prompt used for this extraction (shown in Figure 3 above) instructs the model to create self-contained sentences without pronouns, ensuring each claim can be verified independently.

Step 2: Classification with Reasoning

Once the claims are extracted, they must be classified. This is where HalluMeasure distinguishes itself from previous methods like RefChecker or AlignScore.

The researchers classify claims into 5 high-level labels:

- Supported: The context confirms the claim.

- Contradicted: The context says the opposite (Intrinsic Hallucination).

- Absent: The context doesn’t mention this information (Extrinsic Hallucination).

- Partially Supported: The claim is mostly right but has a minor error (like a missing attribution).

- Unevaluatable: The claim isn’t a factual statement (e.g., a question).

However, simply asking an LLM to pick a label often leads to poor performance. The model might “guess” based on its own training data rather than the provided context. To solve this, the researchers utilized Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting.

The Power of “Thoughts”

In the CoT configuration, the classifier isn’t just asked for a label; it is asked to generate a “Thought” first. It must explain why a claim matches or conflicts with the text before assigning the label.

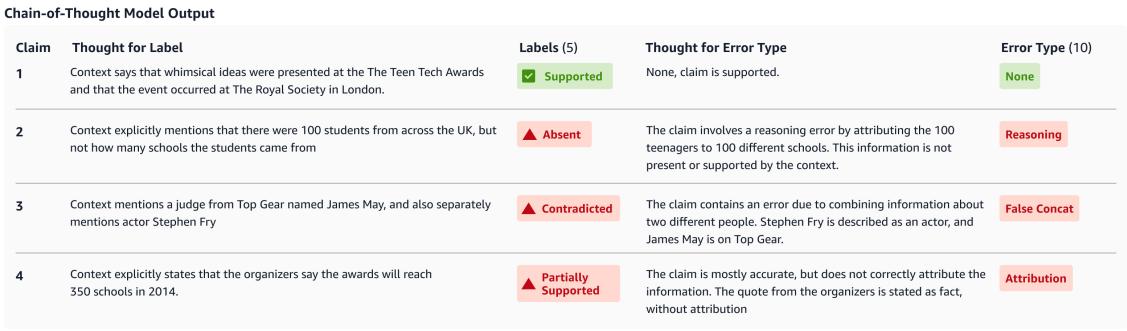

Figure 2 provides a perfect example of this mechanism in action. Look at Claim 2 in the image:

- Claim: “…students came from 100 different schools.”

- Thought: “Context explicitly mentions that there were 100 students from across the UK, but not how many schools the students came from.”

- Label: Absent.

By forcing the model to articulate the discrepancy (100 students vs. 100 schools), the system reduces the likelihood of the model glossing over subtle numerical errors.

Fine-Grained Error Types

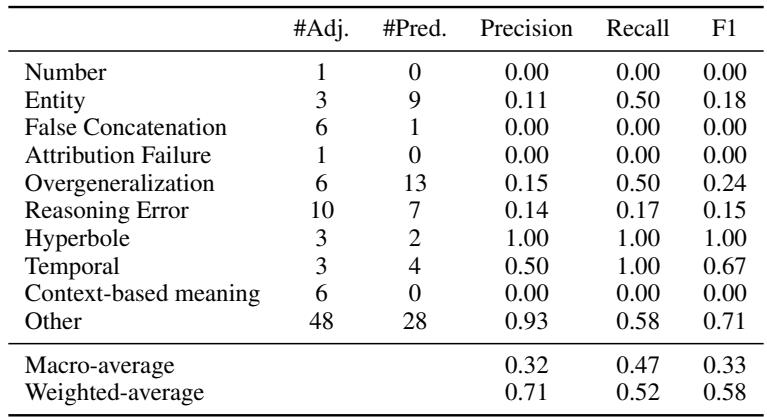

Beyond the main labels, the system attempts to categorize the type of error. This is crucial for developers trying to debug their LLMs. Is the model bad at math? Is it confusing entities?

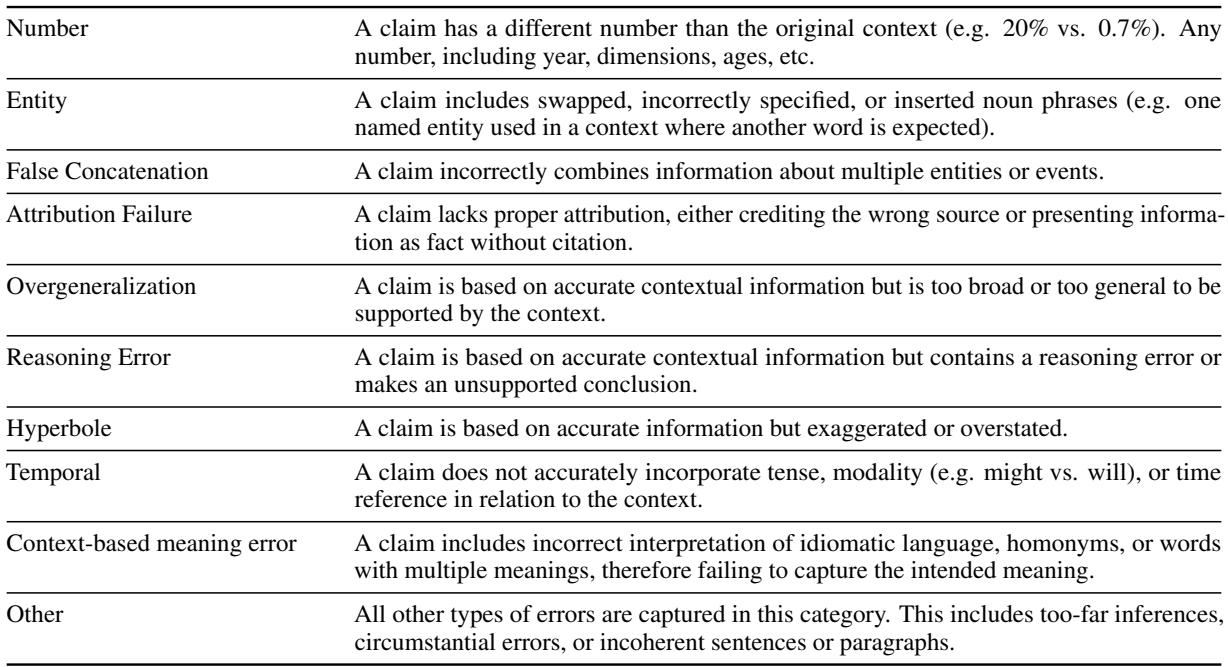

As listed in Table 2, the model identifies 10 specific error subtypes, including:

- Entity Errors: Swapping names (e.g., saying “Google” instead of “Amazon”).

- False Concatenation: Merging two separate events into one.

- Overgeneralization: Taking a specific fact and making it a broad rule.

- Reasoning Error: The premises are true, but the conclusion drawn by the LLM is flawed.

Step 3: Prompt Engineering Strategies

The researchers didn’t just settle on one prompt. They experimented with four distinct configurations to find the optimal balance between accuracy and cost:

- Without CoT vs. With CoT: Does the reasoning step actually help?

- All-claims-eval vs. One-claim-eval: Should we send all 10 claims to the LLM in one prompt (Batch), or send them one by one (Individual)?

Below is the prompt for the With CoT + One-claim-eval setup. This is the most computationally expensive but theoretically most accurate configuration. Note the detailed instructions requiring the model to “Thoroughly analyze” before deciding.

Conversely, the prompt below shows the Without CoT version. It skips the reasoning requirement, asking the model to jump straight to the label.

Experiments and Results

To test HalluMeasure, the authors curated a new dataset called TechNewsSumm (summaries of tech news articles) and also used the established SummEval benchmark. They compared their method against industry baselines:

- Vectara HHEM

- AlignScore

- RefChecker

Does Chain-of-Thought Work?

The results were decisive. Adding Chain-of-Thought reasoning significantly boosted performance.

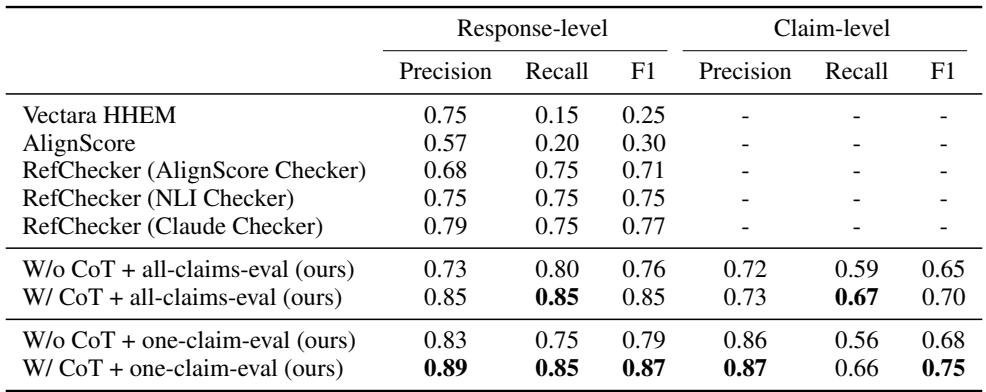

In Table 4, look at the F1 scores for the binary classification (Supported vs. Unsupported).

- RefChecker (Claude) achieved an F1 of 0.77.

- HalluMeasure (No CoT) achieved 0.79.

- HalluMeasure (With CoT + One-claim-eval) achieved 0.87.

This 10-point jump in F1 score on the TechNewsSumm dataset demonstrates that when the model is forced to explain its reasoning, it becomes significantly better at detecting hallucinations.

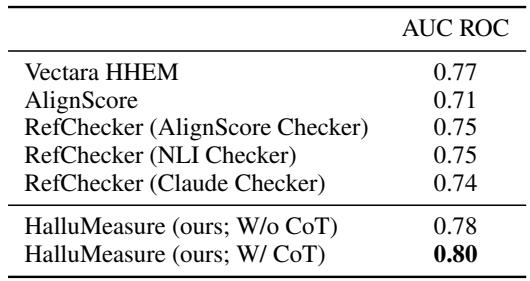

Similarly, on the public SummEval benchmark, HalluMeasure outperformed all baselines.

As seen in Table 7, HalluMeasure reached an AUC ROC of 0.80, surpassing Vectara (0.77) and AlignScore (0.71).

The Trade-off: Accuracy vs. Efficiency

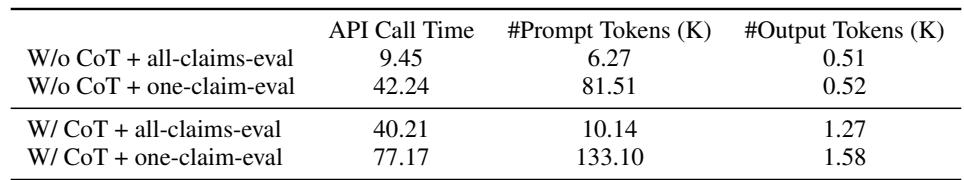

While checking claims one by one with Chain-of-Thought yields the best accuracy, it is slow and expensive.

Table 5 highlights this trade-off. The “All-claims-eval” (batching claims together) took about 9.45 seconds (without CoT), whereas the “One-claim-eval” took 42.24 seconds. When you add CoT, the latency and token count increase further.

However, for applications where accuracy is paramount—such as legal summarization or medical advice—the extra computational cost of the “One-claim-eval + CoT” method is likely a necessary investment.

Can It Diagnose the Type of Error?

While HalluMeasure excels at detecting that an error occurred, it struggles to accurately identify exactly what type of error it is (e.g., distinguishing a “Reasoning Error” from a “Context-based meaning error”).

Table 6 shows low precision and recall for specific subtypes. The researchers attribute this to the difficulty of the task—even humans struggle to agree on these specific labels (inter-annotator agreement was only moderate). Some categories, like “Reasoning Error,” are inherently subjective and overlap with others.

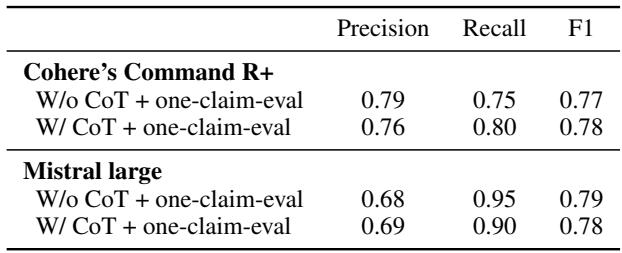

Generalization to Other LLMs

The primary experiments used Claude 3 Sonnet. The researchers also tested if the method works when using open-weights models like Mistral Large or Cohere Command R+.

Interestingly, Table 8 shows that Mistral Large performed quite well, achieving an AUC ROC of 0.81 on SummEval (actually slightly edging out Claude in that specific metric), proving that this CoT methodology is not limited to a single proprietary model.

Conclusion

The “HalluMeasure” paper presents a compelling argument for moving away from simple similarity scores and toward agentic evaluation. By decomposing complex text into atomic claims and forcing the evaluator to “show its work” through Chain-of-Thought reasoning, we can achieve much higher reliability in hallucination detection.

Key Takeaways:

- Decomposition is key: You cannot accurately judge a paragraph without breaking it into claims.

- Reasoning reduces errors: LLMs are better judges when they are prompted to explain their logic before voting.

- One-by-one analysis wins: evaluating claims individually is more accurate than batch evaluation, though significantly more expensive.

As LLMs continue to evolve, the tools we use to verify them must evolve in parallel. HalluMeasure represents a significant step forward, offering a blueprint for building automated fact-checkers that might one day be reliable enough to prevent the next AI legal disaster or stock market crash.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-3153/images/cover.png)