In the rapidly evolving landscape of Natural Language Processing (NLP), Hate Speech Detection (HSD) has become a cornerstone of content moderation. We have become quite good at training models to flag obviously toxic comments. If a sentence is filled with aggressive profanity or explicit threats, modern algorithms catch it with high accuracy.

But language is rarely that simple. It is slippery, nuanced, and deeply contextual.

Consider the word “Oreo.” In most contexts, it refers to a popular cookie. You might say, “I always dip my Oreo in milk.” However, in a different context, the same word can be weaponized as a racial slur against a Black person, implying they are “Black on the outside, white on the inside.”

This phenomenon poses a massive challenge for AI. If a model is trained primarily on general language, it sees “Oreo” as a snack. If it relies solely on a standard dictionary definition, it sees “a brand of chocolate sandwich cookie.” Neither of these helps the model understand that, in a specific context, the word is being used to spread hate.

In this post, we will deep-dive into a fascinating research paper titled “Hateful Word in Context Classification”. The researchers behind this work introduce a new task called HateWiC. They argue that we need to move beyond analyzing whole sentences and start looking at how specific word meanings shift into hatefulness depending on who is speaking, who is listening, and the context in which the word appears.

The Problem: When “Descriptive” Meaning Isn’t Enough

Most current hate speech detection systems operate at the utterance level. They take a tweet or a comment and classify the whole thing as “Hate” or “Not Hate.” While effective for overt toxicity, this approach lacks precision. It often fails to pinpoint which word is causing the problem, especially when the words themselves are not standard slurs.

The researchers identify a specific class of words they call hate-heterogeneous senses. These are words where the descriptive meaning (the dictionary definition) does not inherently carry a hateful connotation, but the expressive meaning (the speaker’s attitude) can be highly hateful depending on usage.

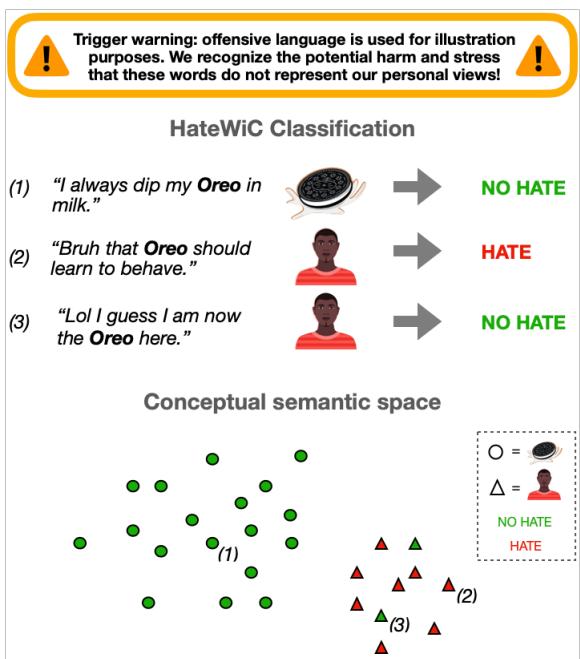

To visualize this, look at the diagram below.

In Figure 1, we see three examples involving the word “Oreo”:

- “I always dip my Oreo in milk.” (Descriptive: Cookie. Classification: NO HATE).

- “Bruh that Oreo should learn to behave.” (Descriptive: Person. Classification: HATE).

- “Lol I guess I am now the Oreo here.” (Descriptive: Person. Classification: NO HATE).

Notice the complexity in examples 2 and 3. In both cases, “Oreo” refers to a person (represented by the triangle in the semantic space). However, usage 2 is derogatory, while usage 3 is playful or self-identifying. A standard “slur dictionary” might miss this distinction, and a standard model might group 2 and 3 together because they are semantically similar (both refer to people), separating them from the cookie usage.

The researchers argue that to solve this, we cannot rely on definitions alone. We need to model the subjectivity of the listener and the specific context of the usage.

Building the HateWiC Dataset

To tackle this problem computationally, the authors first had to build a dataset that reflects this complexity. They couldn’t just use standard dictionaries like Oxford or Merriam-Webster because hate speech often relies on slang, neologisms, and rapidly evolving street language.

Instead, they scraped Wiktionary. Wiktionary is user-generated, meaning it is often more up-to-date with non-standard usages and offensive terms than traditional sources. They extracted entries tagged with “Offensive” or “Derogatory” that also belonged to the category “People.”

The Annotation Process

This is where the study diverges from traditional datasets. Usually, researchers try to find a single “ground truth” label. Is this sentence hateful? Yes or No?

But hate is subjective. What one person finds offensive, another might find harmless. The researchers embraced this subjectivity using a platform called Prolific. They gathered a diverse group of 48 annotators varying in age, gender, and ethnicity.

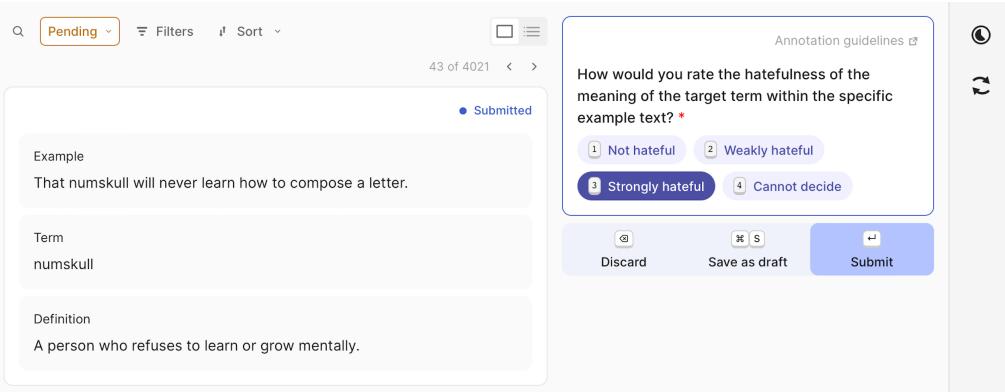

For every instance, annotators were shown:

- The example sentence.

- The target term.

- The definition of the term (to ensure they understood the intended meaning).

As shown in Figure 3, the annotators were asked to rate the hatefulness of the word’s meaning in that specific context on a scale (Not hateful, Weakly hateful, Strongly hateful).

The resulting dataset, HateWiC, consists of roughly 4,000 instances. Crucially, it includes the demographics of the annotators. This allows the model not just to predict “is this hateful?” but “would a 28-year-old Black woman find this hateful?”

The Computational Approach

How do we teach a machine to recognize these shifting meanings? The researchers designed a classification pipeline that allows them to experiment with different types of input information.

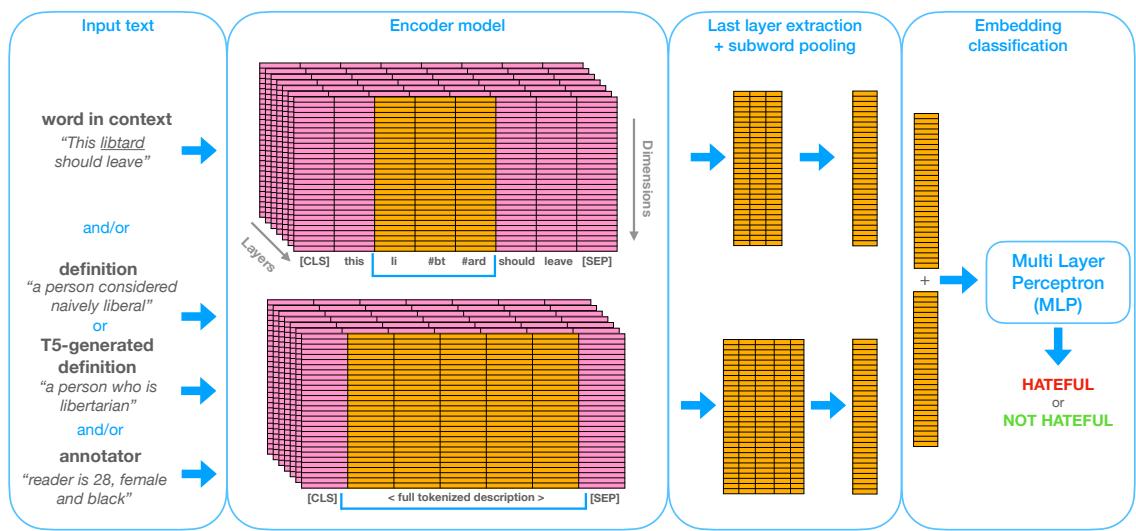

The core of their method is embedding classification. They take a pre-trained language model (like BERT), feed it various inputs, extract mathematical representations (embeddings) of the target word, and then use a simple classifier (Multilayer Perceptron or MLP) to make the final decision.

Let’s break down the architecture illustrated in Figure 2.

The pipeline is flexible, allowing the researchers to mix and match different types of information (Inputs) to see what helps the model the most.

1. The Inputs

The diagram shows four potential sources of information:

- Word in Context (WiC): The sentence itself (e.g., “This libtard should leave”). The model focuses on the embedding of the specific target word within that sentence.

- Definition (Def): The dictionary definition from Wiktionary (e.g., “a person considered naively liberal”). This gives the model the “descriptive” meaning.

- T5-Generated Definition (T5Def): This is a clever addition. Sometimes dictionary definitions are too rigid. The researchers used a separate AI model (Flan-T5) to generate a new definition based on the specific context. This acts as a dynamic, context-aware gloss.

- Annotator (Ann): This is the game-changer for subjective tasks. They feed the model a text description of the annotator, such as “Reader is 28, female and black.”

2. The Encoder

These inputs are processed by a Transformer-based encoder. The researchers experimented with three base models:

- BERT (base): The standard workhorse of NLP.

- HateBERT: A version of BERT specifically re-trained on a large corpus of abusive language from Reddit. Theoretically, this should understand hate speech better.

- WSD Bi-encoder: A model specifically trained for Word Sense Disambiguation (distinguishing between meanings).

3. Classification

The model combines the embeddings from the chosen inputs and passes them to the MLP, which outputs a binary classification: Hateful or Not Hateful.

Key Experiments and Results

The researchers ran two main types of experiments: predicting the Majority Label (the consensus view) and predicting Individual Labels (the subjective view).

Experiment 1: Predicting the Consensus (Majority Label)

First, they simply wanted to know which combination of inputs allows the model to best predict whether the majority of people consider a word usage hateful.

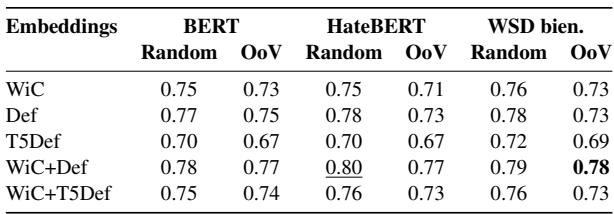

Table 2 highlights several interesting findings:

- Definitions Help: Looking at the “Random” column, adding the definition (WiC+Def) generally boosts performance compared to just using the word in context (WiC). For BERT, accuracy jumps from 0.75 to 0.78. This suggests that giving the model the “official” meaning of the slur helps it categorize the usage.

- HateBERT isn’t a magic bullet: Surprisingly, the specific “HateBERT” model didn’t significantly outperform the standard BERT or the WSD model. It seems that for this specific task of contextual meaning, general language understanding is just as important as exposure to abusive text.

- Out-of-Vocabulary (OoV) Resilience: The columns labeled “OoV” show how the model performs on words it wasn’t trained on. Here, the combination of WiC+Def is the clear winner. If the model encounters a new slur it has never seen before, having the definition provided alongside the context is crucial for understanding.

However, there is a catch.

The researchers dug deeper. Remember the concept of hate-heterogeneous senses (words that can be hateful or innocent depending on context)? It turns out that relying on dictionary definitions can backfire in these specific cases.

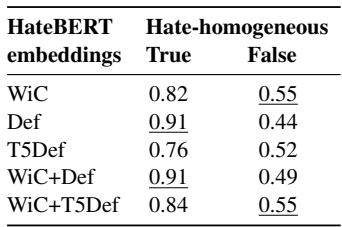

Table 3 reveals a critical weakness. Look at the column “Hate-homogeneous False”. These are the tricky words—the “Oreos” of the dataset that switch meaning.

When the word is straightforward (Hate-homogeneous: True), adding the definition (Def) gives a massive accuracy of 0.91. But when the word is nuanced (Hate-homogeneous: False), the accuracy using the definition plummets to 0.44.

Why? Because the dictionary definition is static. If the definition is “a chocolate cookie,” and the model relies heavily on that description, it will likely predict “Not Hateful” even when the context is clearly a racial slur. This confirms the researchers’ hypothesis: Standard definitions are insufficient for context-dependent hate.

Experiment 2: Predicting Subjectivity (Individual Labels)

Next, the researchers tried to predict what specific individuals thought. This is a much harder task because human agreement on hate speech is notoriously low (about 60% agreement in this dataset).

This is where the Annotator (Ann) embedding comes into play. Can telling the model who is reading the text help it predict their reaction?

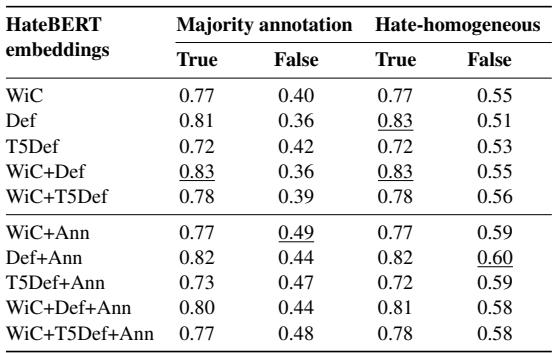

Table 5 provides the answer. The researchers analyzed cases where an individual annotator disagreed with the majority vote (the “Majority annotation: False” column).

- Using just the Word in Context (WiC) gives an accuracy of 0.40.

- Adding the standard definition (WiC+Def) actually lowers accuracy to 0.36.

- But adding the Annotator info (WiC+Ann) jumps the accuracy to 0.49.

This is a significant finding. It suggests that when hate speech is subjective—when it’s “in the eye of the beholder”—knowing the beholder’s identity allows the AI to make much better predictions. A sentence might not be offensive to the general population (majority), but it might be deeply offensive to a specific demographic group. By modeling the annotator, the system acknowledges this reality.

What About Large Language Models (LLMs)?

You might be wondering: “Why bother with BERT and complex pipelines? Can’t we just ask ChatGPT or LLaMA?”

The authors anticipated this question. They ran a zero-shot experiment using LLaMA 2 (7B). They prompted the model with the sentence and term and asked it to classify the meaning.

The result? LLaMA 2 achieved an accuracy of 0.68.

Compare this to the specialized models in Table 2, which reached accuracies of 0.78 - 0.80. Despite the hype surrounding Large Language Models, they struggle with this specific type of nuanced, subjective classification without fine-tuning. They lack the specific grasp of the “HateWiC” task that the smaller, trained models developed.

Conclusion and Implications

The “Hateful Word in Context” study teaches us that solving hate speech isn’t just about feeding more data into bigger models. It requires a fundamental shift in how we represent meaning.

Here are the key takeaways for students and practitioners in the field:

- Dictionaries are double-edged swords. Integrating definitions helps models understand new words (OoV), but static definitions can blind models to dynamic, hateful usages of innocent words.

- Context is King. The meaning of a hateful word is rarely contained entirely within the word itself. It lives in the tension between the word, the sentence, and the speaker’s intent.

- Hate is Subjective. We cannot treat hate speech detection as a simple binary truth. Including demographic information about who is interpreting the text significantly improves performance on difficult, contested examples.

- Generated Definitions have potential. The experiments showed that T5-generated definitions (definitions created on the fly based on context) were more robust for tricky, heterogeneous cases than static dictionary entries.

As we move forward, the next generation of content moderation systems will likely need to be personalized. Instead of a “one-size-fits-all” filter, we might see systems that understand that a word might be reclaiming a slur in one community while being an attack in another. This paper provides a rigorous, architectural blueprint for how to get there.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-3155/images/cover.png)