If you are a software developer, or studying to become one, you are likely familiar with the “Friday afternoon commit.” You’ve just finished a complex bug fix, you’re tired, and the last thing you want to do is write a detailed explanation of why you changed those ten lines of code. You type git commit -m "fix bug" and call it a day.

While understandable, this habit creates a nightmare for code maintainability. Commit messages are the historical record of a software project. They explain the intent behind changes, making it possible for future developers (or your future self) to understand the evolution of the codebase without re-reading every line of code.

Because this is such a tedious task, researchers have long tried to automate it. However, most existing tools struggle with a fundamental problem: they only look at the Diff—the literal lines added or removed. They lack Context.

In this post, we will deep dive into a fascinating research paper titled “Leveraging Context-Aware Prompting for Commit Message Generation”. We will explore how the researchers developed a new model, COMMIT, which uses Code Property Graphs (CPGs) to understand the semantic relationships between changed code and the surrounding program, significantly outperforming even massive Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-3.5 and Code-Llama in generating accurate summaries.

The Problem: Why Diffs Aren’t Enough

To understand the innovation here, we first need to understand the limitation of current methods. Most automatic commit message generators treat code changes like text translation. They take the “Diff” as input and try to “translate” it into English.

The problem is that a Diff tells you what changed, but rarely why.

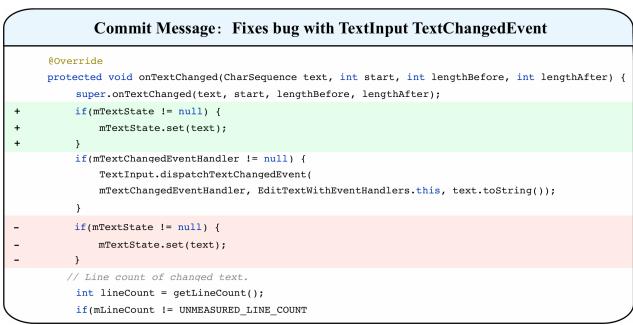

Consider the example below.

In Figure 1, notice the change. The developer removed a check for mTextState != null and added a check for mTextState == null. Litterally, the added and deleted codes look very similar. A simple text-based model might look at this and get confused, or simply say “Changed condition.”

However, the real logic—the reason this change fixes a bug—relies on how mTextState interacts with other parts of the code that weren’t changed. Without analyzing the dependencies (the context), an AI model is essentially guessing.

Existing methods fall into two traps:

- Context-Blindness: They only look at the changed lines.

- Noise: They grab the nearest 5-10 lines of code, hoping they are relevant. Often, they aren’t, introducing noise that confuses the model.

The researchers behind COMMIT argue that we need a way to surgically extract only the relevant context—lines of code that are programmatically dependent on the changes.

Background: The Power of Code Property Graphs

Before understanding the solution, we need to introduce a core concept used in this paper: the Code Property Graph (CPG).

In computer science, we have different ways of representing code as graphs:

- Abstract Syntax Tree (AST): Represents the hierarchical structure of the code (loops nested in functions, etc.).

- Control Flow Graph (CFG): Represents the order in which statements are executed.

- Program Dependence Graph (PDG): Represents how data flows (variables used in line A are defined in line B) and control dependencies (line B only executes if the

ifstatement in line A is true).

A Code Property Graph (CPG) combines all of these into one massive, super-informative graph. By traversing a CPG, you can answer complex questions like, “Which specific line of code defined the variable that is being used in this changed line?”

This is the secret weapon of the COMMIT model. It doesn’t guess which context is important; it calculates it.

The Data: Introducing CODEC

Machine learning models are only as good as their training data. The researchers realized that existing datasets for commit message generation were insufficient. Some were too small, some were noisy (containing bot-generated messages), and crucially, none of them contained the rich context data needed for graph analysis.

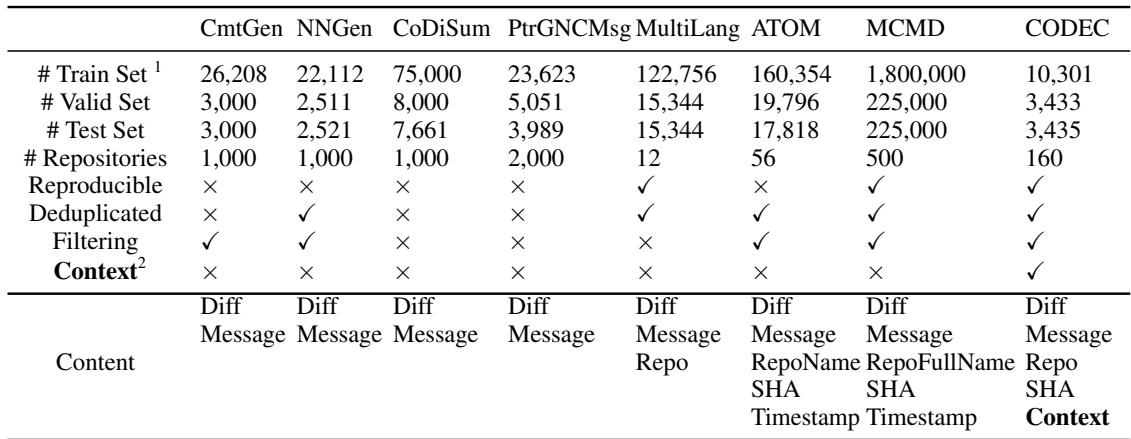

To solve this, they constructed CODEC (COntext and metaData Enhanced Code dataset).

As shown in Table 1, CODEC differs from datasets like NNGen or MCMD. It includes not just the Diff and the Message, but also the repo name, SHA, and crucially, the Context.

They collected data from top Java repositories on GitHub, filtering out massive changes (over 20 lines) and tiny messages (under 5 words) to ensure high quality. They also used a Bi-LSTM model to filter out messages that didn’t answer “Why” or “What,” ensuring the training data consisted of meaningful summaries.

The Core Method: COMMIT

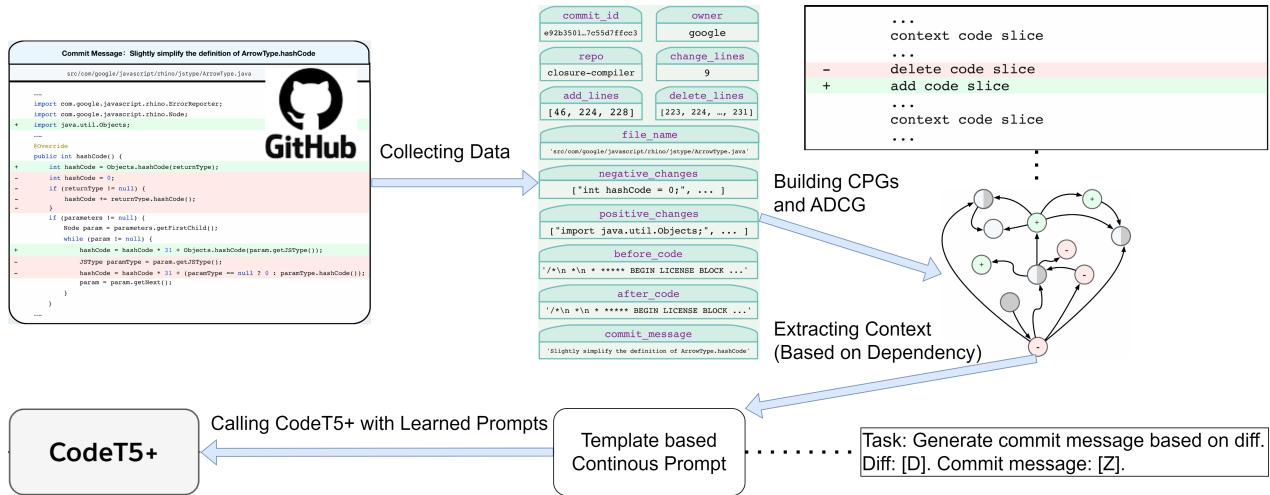

Now, let’s look at the architecture of the solution. The model is called COMMIT (Context-aware prOMpting based comMIt-message generaTion).

The workflow involves three main phases:

- Graph Construction: Building graphs for the code before and after changes.

- Context Extraction: Using those graphs to find relevant dependencies.

- Generation: Using a pre-trained model (CodeT5+) with a specific prompt to write the message.

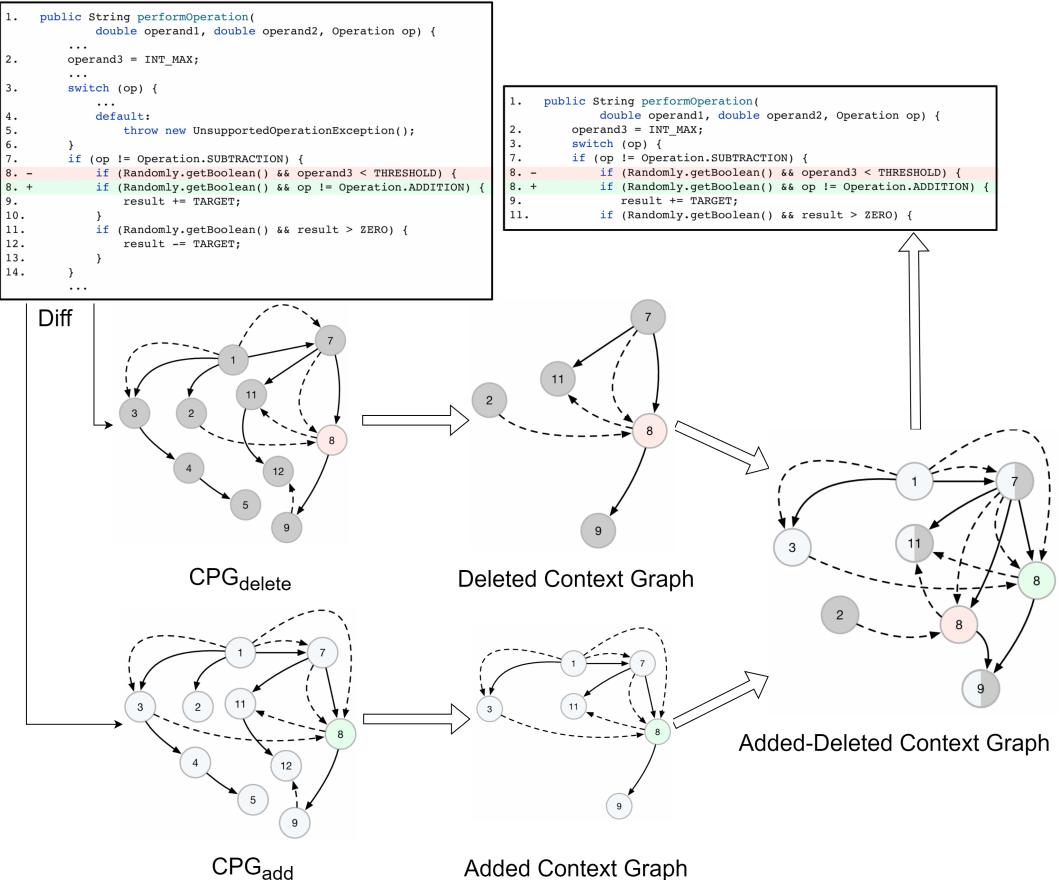

1. Building the Added-Deleted Context Graph (ADCG)

This is the most technically novel part of the paper. When code changes, you essentially have two versions of the program: the “old” version (where lines were deleted) and the “new” version (where lines were added).

The researchers use a tool called Joern to build CPGs for both versions.

- \(CPG_{delete}\): The graph of the file before the change. Deleted nodes are marked red.

- \(CPG_{add}\): The graph of the file after the change. Added nodes are marked green.

They then merge these two graphs into a single super-graph called the Added-Deleted Context Graph (ADCG).

In the ADCG, nodes (lines of code) that didn’t change are merged. This graph now contains the history of the change. It allows the system to trace relationships between:

- Deleted lines.

- Added lines.

- Context lines relevant to deletions.

- Context lines relevant to additions.

2. Dependency Extraction via Slicing

Once the ADCG is built, the model needs to find the “Goldilocks” context—not too little, not too much. It does this via Program Slicing.

The algorithm looks at the changed nodes (added or deleted) and traces the edges in the graph to find connected nodes. It looks for two specific types of connections:

- Data Dependency: “Line A defines variable X, and Line B uses variable X.”

- Control Dependency: “Line A is an

ifstatement, and Line B is inside that block.”

Figure 3 illustrates this beautifully.

- Red nodes (-8): The deleted line.

- Green nodes (+8): The added line.

- Grey nodes: The context.

Notice the arrows. The algorithm traces back from the change (Line 8) to find that Line 7 (int lengthAfter) and Line 2 (CharSequence text) are dependencies. These lines weren’t changed, but you cannot understand Line 8 without them.

The algorithm limits this search to a specific depth (the researchers found a depth of 3 hops was optimal) to prevent pulling in the entire file.

3. Context-Aware Prompting with CodeT5+

Now that the system has the Diff and the mathematically extracted Context, it needs to generate the text.

The researchers utilized CodeT5+, a state-of-the-art encoder-decoder model pre-trained on code. Instead of simply fine-tuning it, they employed Prompt Tuning. They designed specific templates that structure the input for the model.

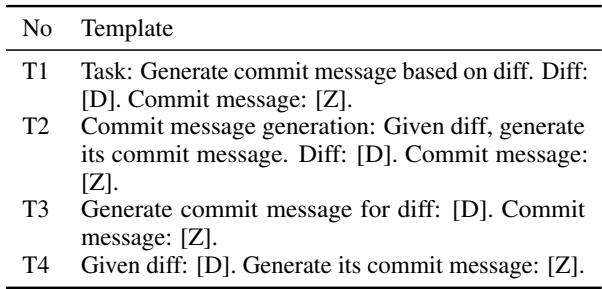

As seen in Table 2, they experimented with different ways to ask the model for a summary. The input isn’t just the code; it’s a structured prompt containing the task description and the context-enhanced diff.

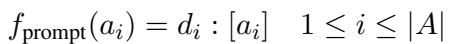

Mathematically, they model the prompt function as:

Where they concatenate the task description, the diff, and the target message slot:

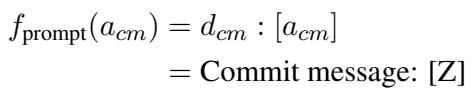

The model is then trained to maximize the probability of generating the correct commit message (\(S\)) given the input (\(X\)) and the prompt (\(f_{prompt}\)):

Experiments and Results

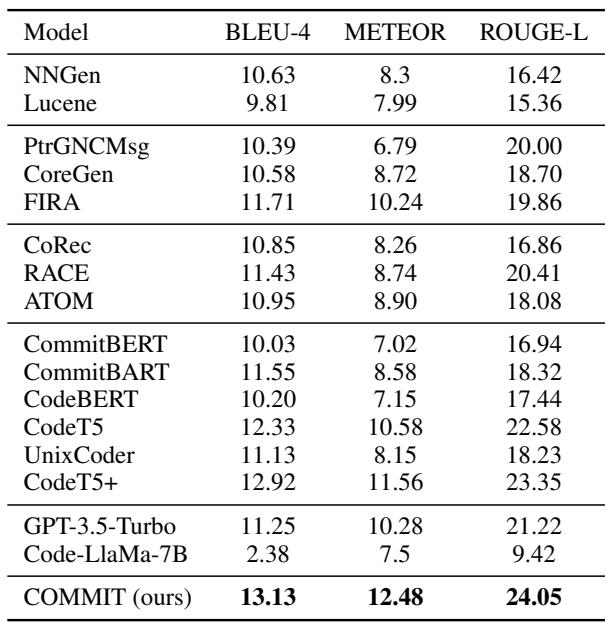

The researchers compared COMMIT against 16 other models, ranging from simple information retrieval systems to massive LLMs like GPT-3.5 and Code-Llama.

Quantitative Results

The results were decisive. COMMIT achieved the highest scores across all major metrics:

- BLEU-4: Measures n-gram overlap (precision).

- METEOR: Aligns with human judgment better than BLEU.

- ROUGE-L: Measures longest common subsequence (recall/structure).

As Table 3 shows, COMMIT (13.13 BLEU-4) outperforms CodeT5+ (12.92) and significantly beats GPT-3.5 (11.25) and Code-Llama (2.38).

Why did the LLMs fail? It is interesting to note Code-Llama’s low score. The researchers found that Code-Llama tends to be overly verbose, generating lengthy paragraphs explaining the code rather than the concise, single-sentence summary required for a commit message. COMMIT, being fine-tuned with context-aware prompts, learned the specific style required.

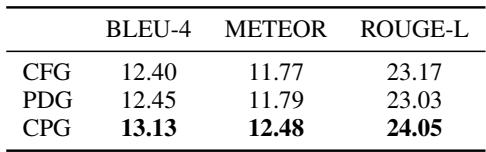

The Importance of CPGs

Was all that complex graph construction worth it? The researchers ran an ablation study to compare different graph types.

Table 4 confirms that the CPG representation yields better results (13.13 BLEU) than using just a Control Flow Graph (CFG) or Program Dependency Graph (PDG) alone. The combination of structural and flow information provides the most complete picture.

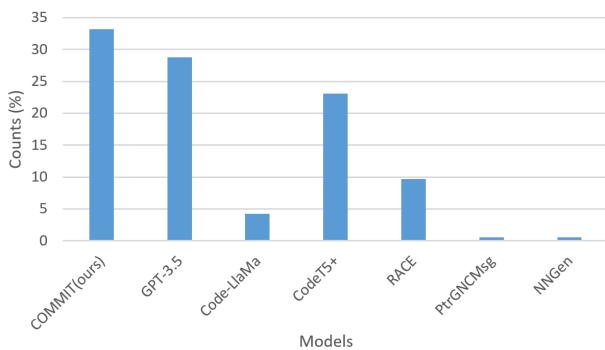

Human Evaluation

Automatic metrics like BLEU are not always perfect proxies for quality. A sentence can have low word overlap but still mean the same thing. To address this, the researchers conducted a human evaluation.

They asked participants to review code changes and select the best commit message from a list of anonymous outputs generated by different models.

The results in Figure 4 are striking. COMMIT was preferred in 33.2% of cases, the highest of any model. GPT-3.5 came in second at ~28%. This validates that the model isn’t just gaming the metrics; it’s producing summaries that developers actually find useful.

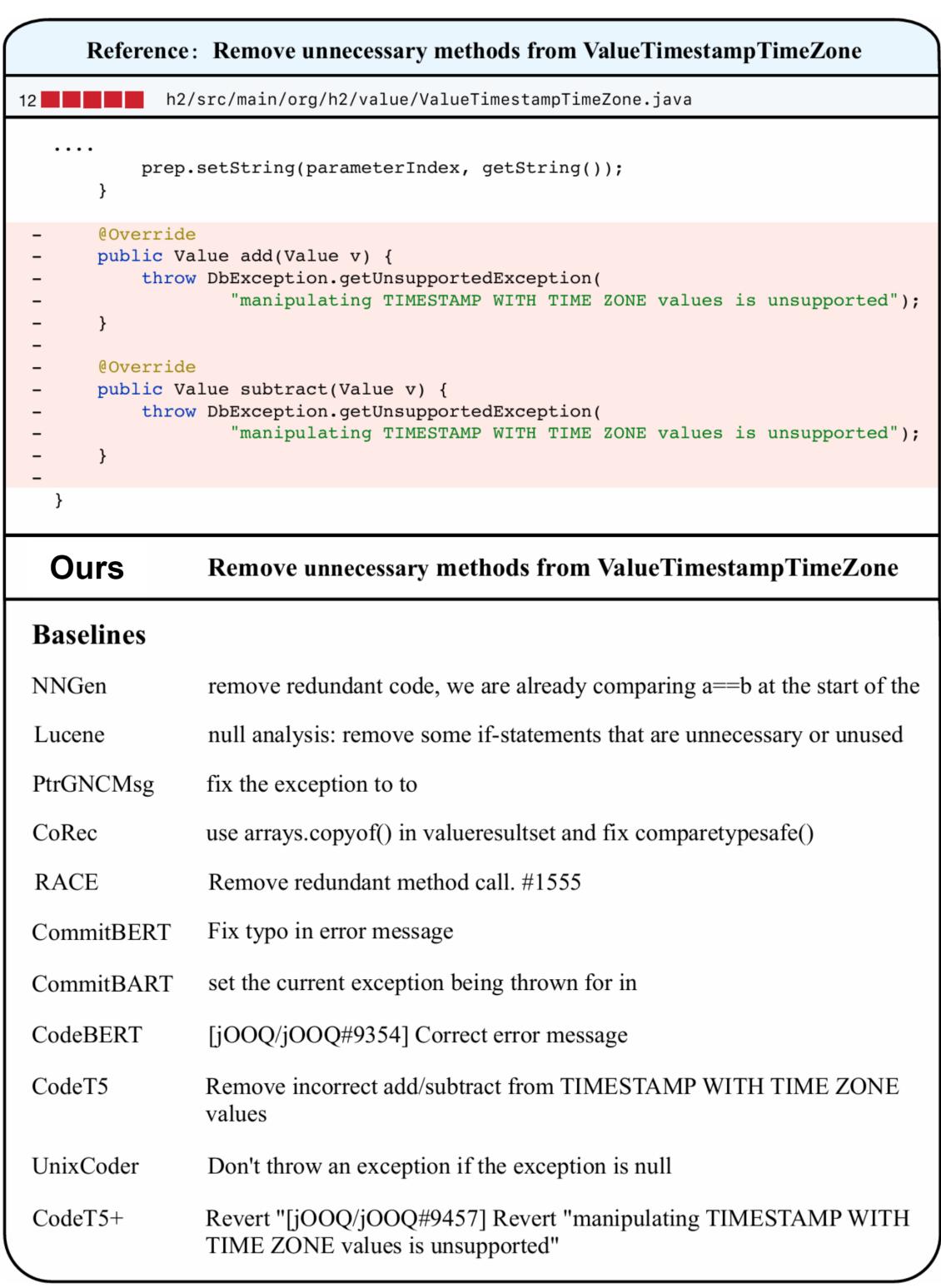

Case Study: Seeing the Difference

Let’s look at a concrete example of the output to see why COMMIT works better.

In this example, the developer removed add and subtract methods from a class called ValueTimestampTimeZone because manipulating these values is unsupported.

- Reference (Human): “Remove unnecessary methods from ValueTimestampTimeZone”

- COMMIT (Ours): “Remove unnecessary methods from ValueTimestampTimeZone” (Exact Match)

- NNGen: “remove redundant code… comparing a==b” (Hallucination - completely irrelevant).

- CodeT5: “Remove incorrect add/subtract…” (Close, but implies they were incorrect, not just unnecessary).

- GPT-3.5: “Remove unsupported operations…” (Good, but slightly wordier).

The baseline models struggle to grasp the intent. They see code removal and guess “fix” or “redundant.” COMMIT, seeing the dependencies and the specific exception types in the context, understands exactly what is happening.

Conclusion and Implications

The COMMIT paper demonstrates a vital lesson for the era of AI coding assistants: Model size is not everything; Context is.

While massive LLMs like GPT-4 and Llama are impressive generalists, specialized tasks like commit message generation require surgical precision. By treating code not just as text, but as a graph of logical dependencies, the researchers were able to feed the model exactly the information it needed—no more, no less.

Key Takeaways:

- Code is a Graph: Treating code as a flat sequence of text ignores its underlying logic. CPGs unlock this logic.

- Context-Awareness: The “Added-Deleted Context Graph” allows models to understand the relationship between what was there and what replaced it.

- Efficiency: A smaller, well-prompted model (CodeT5+) with the right data can outperform a massive generic model (GPT-3.5).

This approach paves the way for smarter developer tools that don’t just autocomplete text, but actually understand the structure and flow of the software they are helping to build. Future work aims to expand this to other languages like Python and C++, potentially making the “Friday afternoon commit” a thing of the past.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-3307/images/cover.png)