Introduction

In the age of Big Data, we have more text than any human could ever read. To make sense of this information, we rely on Relation Extraction (RE)—the process of teaching machines to identify relationships between entities in text. For example, reading “Paris is in France” and extracting the triplet (Paris, Located In, France).

This technology is the backbone of Knowledge Graphs, Question Answering systems, and semantic search. However, as we move from simple sentences to complex documents, the challenge grows exponentially. Document-level Relation Extraction (DocRE) requires understanding connections across long paragraphs, involving multiple entities.

Here is the catch: Training these models requires massive datasets where every possible relationship is labeled. In reality, human annotators miss things. They might label the obvious relationships but miss the subtle ones. This leads to Incomplete Annotations (False Negatives), where the dataset tells the model a relationship doesn’t exist simply because it wasn’t labeled.

How do we train a model on broken data without teaching it to be broken?

In a recent paper titled “LogicST: A Logical Self-Training Framework for Document-Level Relation Extraction with Incomplete Annotations,” researchers propose a fascinating solution: combining the pattern-matching power of deep learning with the strict reasoning of symbolic logic. They introduce LogicST, a framework that uses logical rules as a diagnostic tool to “debug” the model’s predictions during training.

In this post, we will dive deep into how LogicST works, how it uses logic to fix neural networks, and why it outperforms even massive Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 on this specific task.

The Problem: Learning from Incomplete Data

The False Negative Trap

Imagine taking a test where the teacher marks correct answers as wrong simply because they didn’t have time to grade them. If you learn from that feedback, you will stop giving those correct answers.

This is exactly what happens in DocRE. In a document with 20 entities, there are nearly 400 possible pairs. It is almost impossible for annotators to verify every single one. When a dataset contains valid relationships that are not labeled (False Negatives), the model is explicitly trained to predict “No Relation” for them. This suppresses the model’s ability to recall valid facts.

The Limits of Self-Training

A common fix for this is Self-Training. In this setup, a “Teacher” model makes predictions on the data. If the Teacher is confident about a relationship that was missing in the ground truth, we assume the Teacher is right and add it as a “Pseudo-Label.” A “Student” model then trains on these new labels.

However, Self-Training is risky. It suffers from Confirmation Bias. If the Teacher makes a mistake and is confident about it, the Student learns that mistake, reinforcing the error in a vicious cycle. Furthermore, standard self-training is “sub-symbolic”—it looks at statistical patterns but doesn’t understand the logical implications of what it is predicting.

The Solution: LogicST

The authors of LogicST propose a paradigm shift. Instead of just looking at probability scores, we should look at logical consistency.

Deep learning models are “black boxes”—hard to interpret. Symbolic logic, on the other hand, is rigid and clear. If a model predicts (A, part of, B), logic dictates that it must also accept (B, has part, A). If the model predicts the first but denies the second, we have a Logical Conflict.

LogicST uses these rules as a diagnostic tool. By identifying conflicts, the framework can pinpoint exactly where the model is confused and mathematically determine the best way to flip a label (from False to True, or vice versa) to restore logical harmony.

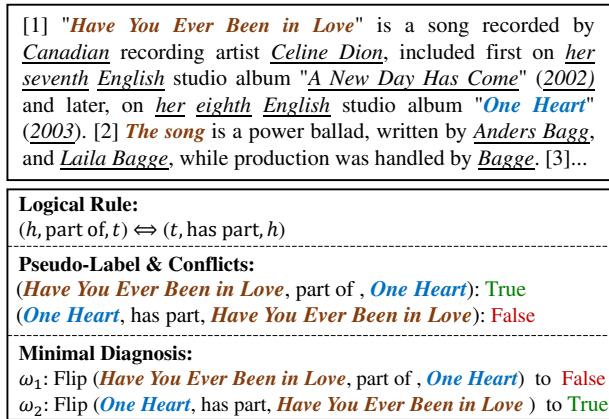

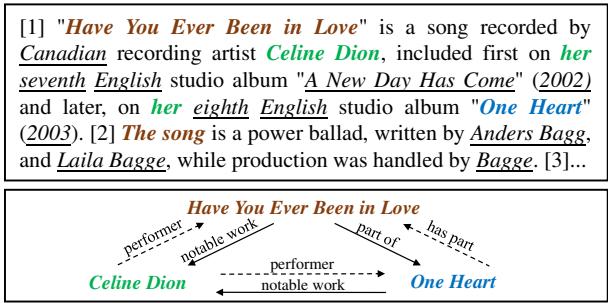

As shown in Figure 1, if the model predicts “Have You Ever Been in Love” is part of “One Heart,” but says “One Heart” does not have part the song, a logical rule is broken. LogicST identifies this and proposes a “Minimal Diagnosis”—the smallest change needed to fix the logic. In this case, flipping the second statement to “True” resolves the conflict and recovers a missing label.

Methodology: Inside the Framework

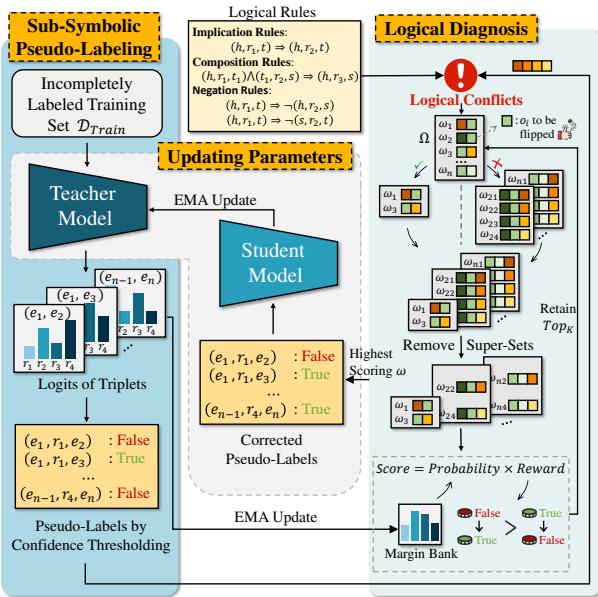

LogicST operates on a Teacher-Student architecture. Let’s break down the workflow.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the process has three main stages:

- Pseudo-Labeling: The Teacher model predicts relationships in the training text.

- Logical Diagnosis: The system checks these predictions against a set of logical rules. If conflicts are found, it calculates the best way to fix them.

- Model Update: The Student model trains on these logically corrected labels. The Teacher is then slowly updated to match the Student (via Exponential Moving Average), and the cycle repeats.

1. The Logical Rules

The researchers define three types of first-order logical rules to govern the extraction process: Implication, Composition, and Negation.

Implication Rules imply that if one relationship exists, another must also exist.

Example: If London is the capital of the UK, London is located in the UK.

Example: If London is the capital of the UK, London is located in the UK.

Composition Rules allow the model to hop between entities to infer new facts.

Example: If Paris is the capital of France, and France is in Europe, then Paris is in Europe.

Example: If Paris is the capital of France, and France is in Europe, then Paris is in Europe.

Negation Rules prevent mutually exclusive relationships.

Example: If X is the spouse of Y, X cannot be the parent of Y.

Example: If X is the spouse of Y, X cannot be the parent of Y.

2. Diagnosing Conflicts

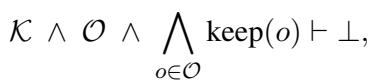

When the Teacher model generates pseudo-labels, LogicST checks them against the rules above. A conflict occurs when the set of predictions (\(\mathcal{O}\)) and the rules (\(\mathcal{K}\)) contradict each other.

Here, \(\vdash \bot\) means the combination leads to a contradiction. To fix this, the system looks for a subset of labels (\(\omega\)) to “flip” (change from True to False or vice versa) so that the contradiction disappears (\(\vdash \top\)).

The goal is a Minimal Diagnosis: finding the smallest number of changes required to make the predictions logically consistent.

3. Sequential Diagnosis: Picking the Best Fix

Often, there are multiple ways to fix a logical error. For example, if A implies B, and we have A=True and B=False, we could either make B=True or A=False. Both solve the logic puzzle, but which is historically or factually correct?

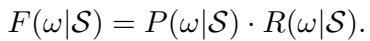

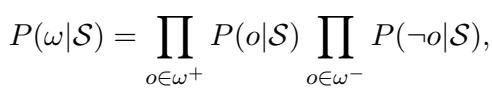

LogicST uses a Scoring Function to evaluate every potential diagnosis. The score is based on two factors: Probability and Reward.

Probability with Adaptive Thresholds

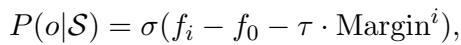

The system calculates the probability of a diagnosis based on how confident the model is.

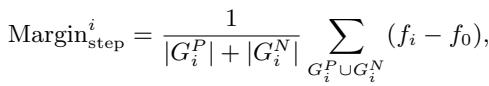

However, simple confidence scores are dangerous because neural networks are biased toward “popular” classes (e.g., located in is common, author of is rare). To fix this, LogicST uses a Margin Bank.

The Margin Bank tracks the model’s performance on different classes over time. It calculates a dynamic margin:

It then uses this margin to adjust the probability calculation, effectively giving a “handicap” to rare classes so they aren’t ignored.

Reward for Discovery

In the early stages of training, the model is likely to have high precision but low recall (it misses a lot of facts). Therefore, LogicST incentivizes “positive flips”—changing a label from False to True—to recover those missing annotations.

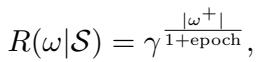

This reward function decays over time as the model improves, shifting the focus from discovery to accuracy.

Experiments and Results

The researchers tested LogicST on major benchmarks like DocRED and DWIE. They compared it against vanilla BERT models, other self-training methods (like CAST), and even Large Language Models.

Performance on Incomplete Data

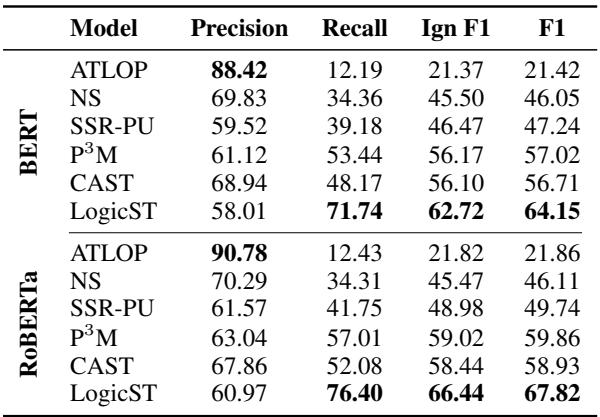

One of the most striking results comes from the Re-DocRED dataset (a version of DocRED with corrected annotations).

In Table 2, we see the results on an “extremely unlabeled” setting. LogicST significantly outperforms the backbone model (ATLOP) and previous state-of-the-art methods like P\(^3\)M and CAST. The jump in Recall (from ~50% to ~76%) highlights LogicST’s ability to find the “needle in the haystack” that other models miss.

Better than LLMs?

Interestingly, the paper compares LogicST against GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 (using Few-Shot learning).

While LLMs are powerful generalists, LogicST outperformed them on this specific task. For example, on the Re-DocRED test set, LogicST achieved an F1 score of 69.26%, whereas GPT-4 (1-shot) only achieved 27.75%. This demonstrates that for specialized, high-precision tasks like Document Relation Extraction, a smaller model trained with symbolic logic and rigorous constraints is often superior to a general-purpose LLM.

Robustness to Data Scarcity

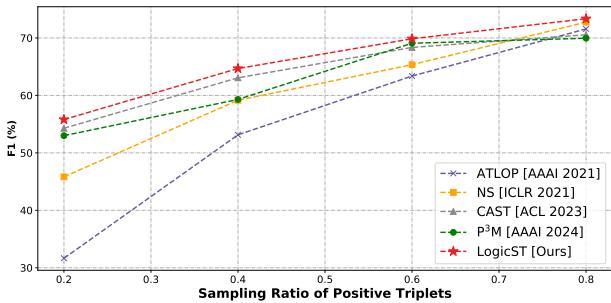

LogicST also shines when positive training samples are scarce.

Figure 3 shows that as we reduce the number of labeled positive triplets (moving left on the X-axis), LogicST (the red line) degrades much slower than other methods. It maintains high performance even when only 20% of the data is labeled, proving that the logical rules effectively fill in the gaps left by human annotators.

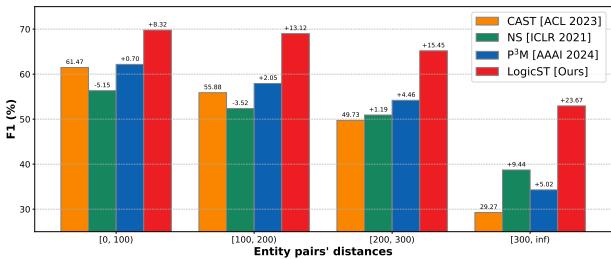

Handling Long-Distance Dependencies

One of the hardest parts of document-level extraction is connecting entities that are far apart in the text.

Figure 4 groups performance by the distance between entity pairs. LogicST’s advantage grows as the distance increases. Why? Because logic is independent of distance. If A implies B, it doesn’t matter if A and B are in the same sentence or three paragraphs apart. The symbolic reasoning bridges the gap that the neural attention mechanism might miss.

Case Study: Logic in Action

To visualize how LogicST works, let’s look at a real example from the study involving the singer Celine Dion.

In Figure 6, the baseline model correctly identified that the song “Have You Ever Been in Love” is part of the album “One Heart.” However, it failed to predict the inverse: that “One Heart” has part the song.

This creates a logical conflict. The Sequential Diagnosis module detected this violation of the rule \((h, \text{part of}, t) \Leftrightarrow (t, \text{has part}, h)\). It evaluated the probabilities and determined the most likely fix was to flip the missing relation to True. The result is a more complete and consistent knowledge graph.

Efficiency

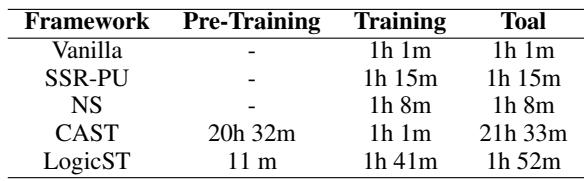

Finally, complex frameworks often come with a heavy computational cost. LogicST, however, is surprisingly efficient.

Table 4 shows that LogicST is significantly faster than its main competitor, CAST. While CAST requires over 20 hours for pre-training, LogicST completes its pipeline in under 2 hours. This is because LogicST doesn’t need multiple rounds of complex re-training; the logical diagnosis happens efficiently during the loop.

Conclusion

LogicST represents a powerful step forward in Neuro-Symbolic AI. It acknowledges that while deep learning is excellent at learning representations from text, it lacks the inherent structure of human reasoning. By injecting explicit logical rules into the training loop, the authors achieved:

- State-of-the-art performance on document-level relation extraction.

- Higher Recall, successfully recovering missing annotations in incomplete datasets.

- Interpretability, as every correction made by the model can be traced back to a specific logical rule.

For students and researchers, LogicST serves as a great example of how we don’t always need “bigger” models. Sometimes, we just need models that “think” a little more logically.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-3322/images/cover.png)