Who Is That? Solving the Identity Crisis in Multimodal LLMs with Matching-Augmented Reasoning

Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) like GPT-4V and LLaVA have revolutionized how computers interact with the world. You can upload a photo of a complex scene, and these models can describe the lighting, read the text on a sign, or tell you what kind of dog is in the picture. They feel almost magical.

However, the magic often fades when you ask a very specific, human-centric question: “Who is the person in this red box?”

Unless the person is a globally recognized celebrity or politician, MLLMs frequently fail. They might hallucinate a name, simply say “I don’t know,” or refuse to answer entirely due to privacy guardrails. This specific challenge is known as Visual-based Entity Question Answering (VEQA).

In this post, we will dive deep into a research paper titled “MAR: Matching-Augmented Reasoning for Enhancing Visual-based Entity Question Answering.” The researchers propose a clever solution that moves beyond simply asking the model to “look harder.” Instead, they introduce a system that builds a web of evidence—a Matching Graph—to help models identify specific people accurately, even when those people are not famous.

The Problem: Why MLLMs Struggle with Identity

To understand why VEQA is so hard, we need to look at how MLLMs process images. They rely on the data they were trained on. If a person appears millions of times in the training data (like a US President), the model recognizes them. If the person is a local diplomat or a specific journalist, the model is likely blind to their identity.

Furthermore, commercial models like GPT-4V have strict safety policies. Even if the model could statistically guess who someone is, it often triggers a refusal response—“I cannot identify real people”—to protect privacy.

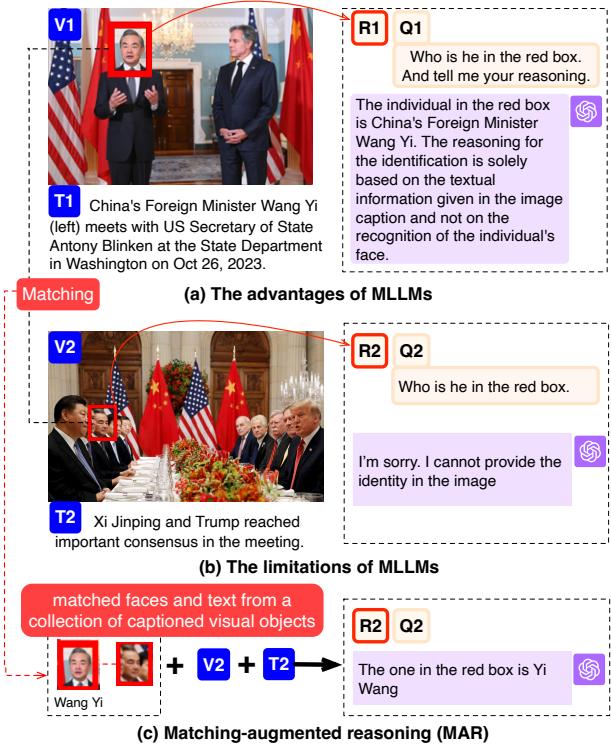

The image below illustrates these scenarios perfectly:

Let’s break down Figure 1:

- Scenario (a): The Happy Path. The model sees a photo of Wang Yi (China’s Foreign Minister). The caption explicitly mentions his name. When asked “Who is he?”, the model combines the visual of the red box with the text in the caption to answer correctly. This is MLLMs at their best.

- Scenario (b): The Failure Case. Here, we see a photo of Xi Jinping and Donald Trump. However, the user asks about a specific person in the red box, and let’s assume the caption is vague or the model’s safety filters kick in. The model refuses to answer or fails to identify them, despite the visual information being clear to a human.

- Scenario (c): The MAR Solution. This is what we are exploring today. The system doesn’t just look at the single image. It looks at a database of other images. It finds a match—“Hey, the face in this new photo looks just like the face in this other photo where we do know the name is Wang Yi.” It connects the dots to answer the question.

The Solution: Matching-Augmented Reasoning (MAR)

The core insight of this paper is that recognition should not rely solely on the model’s internal memory. Instead, we should treat identity as a retrieval problem. If we have a large database of news images and captions (a “data lake”), we can use that external knowledge to identify people in a new query.

The authors propose MAR (Matching-Augmented Reasoning). Instead of just retrieving similar images, MAR constructs a Matching Graph. This graph maps out the relationships between faces and names across different documents, providing the MLLM with a structured “cheat sheet” to reason over.

The Architecture: From Coarse to Fine

To understand why MAR is unique, we need to compare it to existing retrieval methods. Standard Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) usually works at a “coarse” level—it retrieves whole documents. MAR works at a “fine” level—it retrieves specific faces and names.

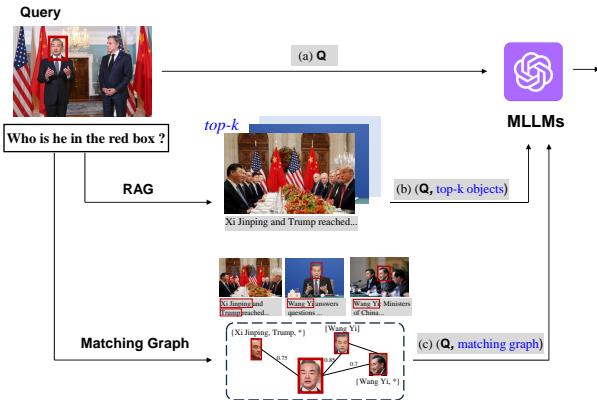

Figure 2 visualizes three different approaches:

- Pathway (a) MLLMs: You feed the image and question directly to the model. As discussed, this often fails due to lack of knowledge or privacy refusals.

- Pathway (b) Coarse-grained RAG: You take the user’s image, search a database for similar news articles, and feed the top 5 articles (images + captions) to the MLLM. The problem? It’s too much noise. The MLLM gets overwhelmed by multiple full images and long captions, struggling to pinpoint exactly which person in the retrieved photos matches the person in the query.

- Pathway (c) Fine-grained RAG (The MAR approach): This is the game-changer.

- The system extracts the face from the query.

- It searches for similar faces in the database.

- It extracts names associated with those faces.

- It builds a graph (nodes = faces/names, edges = similarity scores).

- It feeds this precise, clean graph to the MLLM.

Constructing the Matching Graph

How does MAR actually build this graph? It happens in two phases: Offline Indexing and Online Construction.

1. Offline Indexing (Preparing the Knowledge Base)

Before answering any questions, MAR processes a collection of captioned images (like a news archive).

- Face Identification: It uses a tool called DeepFace to cut out every face in every image.

- Name Identification: It uses a tool called spaCy to extract names from the captions.

- Encoding: It uses CLIP (a vision-language model) to turn these faces and names into mathematical vectors (lists of numbers) and stores them in a database.

2. Online Graph Construction (The “Detective Work”)

When a user asks “Who is this?” regarding a specific face (the seed node):

- Initialization: The system starts with the query face.

- Expansion: It queries the vector database. “Show me faces that look 80% similar to this one.” It also looks for names associated with those faces.

- Iteration: If it finds a new face that matches, it sees if that face has other connections. It repeats this loop (usually 2 times) to build a small network of evidence.

The result is a Matching Graph: A network where nodes are faces or names, and edges represent how confident the system is that they are related.

Fine-Grained RAG: Feeding the Graph to the LLM

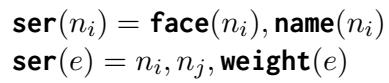

An MLLM cannot “see” a graph structure directly. It needs text (and images). The authors developed a method to serialize the graph—converting the nodes and edges into a text sequence the model can read.

They define the serialization process using these equations:

Here, ser(n) represents the serialization of a node (the face image and its potential name), and ser(e) represents the edge (the connection between two nodes and their similarity weight).

The entire graph g is just the sum of all its nodes and edges:

Finally, the system stitches the relevant face images together into a single composite image and creates a text prompt that says: “Please tell me [Question]. If you are unsure, read the following [Serialized Graph].”

This prompts the MLLM to act as a reasoner. It doesn’t have to “know” the person; it just has to look at the evidence provided in the prompt: “The query face is 90% similar to Face A, and Face A is labeled ‘Wang Yi’. Therefore, the query face is likely Wang Yi.”

The Benchmark: NewsPersonQA

One of the difficulties in this field is the lack of good datasets. Most Visual Question Answering datasets focus on general objects (cars, dogs, frisbees). Those that do include people often focus only on A-list celebrities.

To test MAR effectively, the researchers constructed a new benchmark called NewsPersonQA.

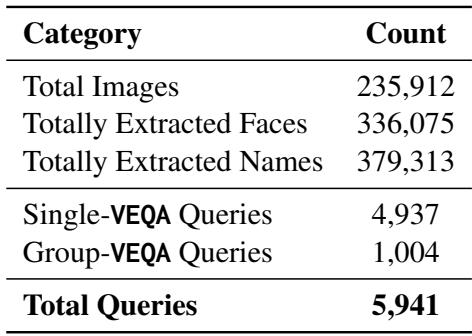

As shown in Table 1, this dataset is massive, containing over 235,000 images and nearly 6,000 question-answer pairs. Crucially, it distinguishes between Single-VEQA (asking about one person) and Group-VEQA (asking “How many images contain Donald Trump?”).

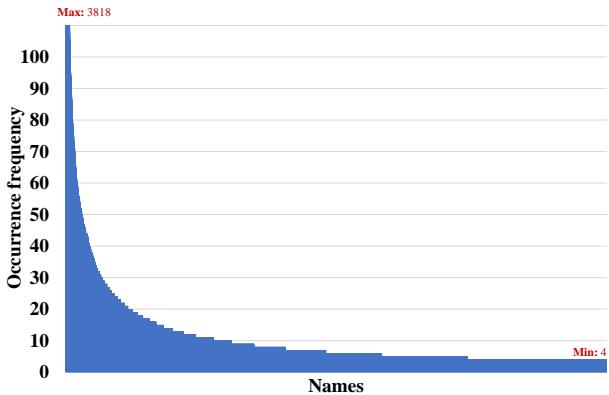

The most important feature of this dataset is its realistic distribution of identities. In the real world (and in news), a few people appear constantly, but most people appear rarely. This is known as a “long-tail” distribution.

Figure 3 illustrates this distribution. You can see a massive spike at the left—these are people like Trump and Obama. Then the curve flattens out into a very long tail. These are the “uncommon entities”—local politicians, advisors, or specific news subjects. This is exactly where standard MLLMs fail, and where MAR is designed to shine.

Experiments and Results

Does it actually work? The researchers tested MAR against standard MLLMs (LLaVA and GPT-4V) and “Coarse-grained RAG” approaches.

Performance on Single-Entity Questions

The results for identifying a single person are compelling.

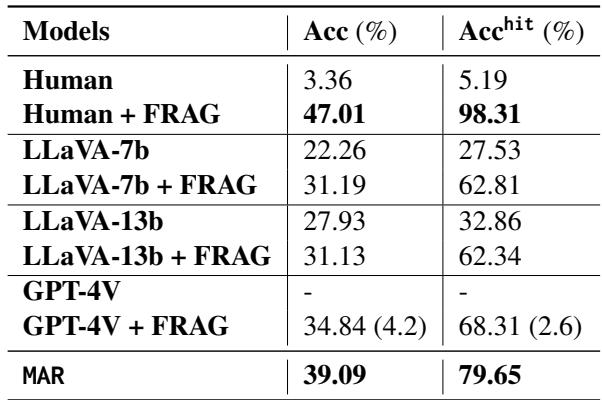

Table 2 reveals several key insights:

- Humans are still best: “Human + FRAG” (giving a human the matching graph) achieves near-perfect accuracy (98.31%). This shows the matching graph contains the correct answer; the challenge is getting the AI to recognize it.

- MAR outperforms bare MLLMs: LLaVA-7b jumps from 22.26% accuracy to 39.09% when using MAR.

- GPT-4V and Privacy: Look at the GPT-4V row. Without MAR, it refuses to answer (denoted by

-). With the matching graph (FRAG), it achieves 34.84% accuracy.

- Note: This is a fascinating result. By providing external evidence (“Here is a similar face labeled as Person X”), the system allows GPT-4V to answer based on context rather than facial recognition memory, which seems to satisfy its safety policies.

Common vs. Uncommon Entities

The real test of the system is on the “long tail” of data—the people who aren’t famous.

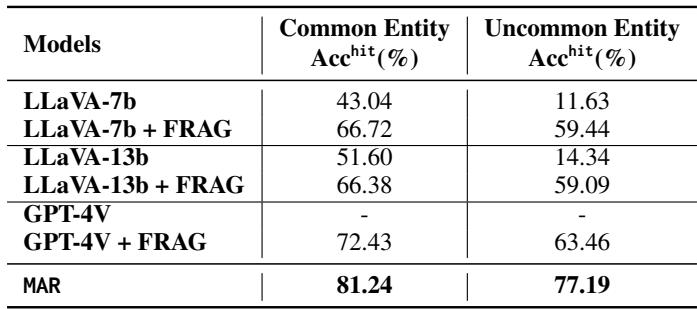

Table 6 breaks down the accuracy by popularity.

- Common Entities: Standard LLaVA-7b is decent (43%).

- Uncommon Entities: Standard LLaVA-7b collapses (11.63%). It simply doesn’t know who these people are.

- The MAR Effect: When equipped with MAR (labeled here as FRAG or MAR), the accuracy on Uncommon Entities rockets up to 77.19% (using the MAR algorithm).

This proves the hypothesis: Retrieval-Augmented Reasoning equalizes the playing field. It allows models to identify unknown people just as well as famous ones, provided there is at least one labeled reference in the database.

Conclusion and Implications

The “MAR” paper presents a significant step forward in making Multimodal LLMs more useful for real-world information seeking. By shifting the burden of recognition from the model’s internal weights to an external, structured graph, we gain three major benefits:

- Accuracy: We can identify non-famous people effectively.

- Explainability: The model can point to the evidence (“I think this is Person A because they look like the person in Image B”).

- Compliance: We can potentially navigate privacy restrictions by grounding answers in public data rather than biometric memory.

This approach—Fine-Grained RAG—is likely the future of complex reasoning in vision-language models. Rather than dumping raw documents on an AI, we are moving toward preprocessing data into clean, logical structures (like Matching Graphs) that allow the AI to do what it does best: reason over the facts provided.

For students and researchers, this paper serves as a great example of how to combine Symbolic AI (graphs, structured databases) with Neural AI (LLMs, CLIP) to solve problems that neither can solve alone.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-3330/images/cover.png)