Imagine you are a Machine Learning engineer responsible for deploying a large language model (LLM) for a hiring platform. You run a standard bias evaluation script, and it returns a score: 0.42.

What do you do now?

Is 0.42 good? Is it terrible? Does it mean the model hates women, or that it slightly prefers Western names? If you fix the data and the score drops to 0.38, is the model safe to deploy?

If you cannot answer these questions, the metric you used lacks actionability.

In the rapidly evolving field of Natural Language Processing (NLP), we have seen an explosion of papers proposing new ways to measure bias. However, a recent paper titled “Metrics for What, Metrics for Whom: Assessing Actionability of Bias Evaluation Metrics in NLP” argues that we are producing tools that are fundamentally difficult to use.

The authors, Pieter Delobelle, Giuseppe Attanasio, Debra Nozza, Su Lin Blodgett, and Zeerak Talat, conducted a comprehensive review of 146 research papers. Their conclusion? The field is suffering from a lack of clarity that prevents us from turning bias measurements into real-world interventions.

In this deep dive, we will explore the concept of actionability, the framework the researchers propose to assess it, and the sobering results of their literature review.

The Gap Between Measurement and Action

To understand why actionability is necessary, we first need to look at the current state of “Fair NLP.”

For years, researchers have utilized frameworks like measurement modeling from social sciences. This approach asks us to distinguish between the construct (the theoretical idea of what we are measuring, like “gender discrimination”) and the operationalization (how we actually measure it, like “counting pronoun mismatches”).

While this distinction is vital for validity (measuring what we think we are measuring), it misses a practical component: utility.

In the real world, metrics are tools for decision-making. In 2014, Amazon famously tried to build an AI system to screen resumes. They discovered the system was penalizing resumes containing the word “women’s” (e.g., “women’s chess club”). Because the results of their internal auditing were clear and actionable, they could take specific steps: they tried to edit the program, and when that failed, they eventually scrapped the project.

The results enabled a decision. That is the essence of actionability.

Defining Actionability

The authors formally define actionability as:

The degree to which a measurement’s results enable informed action.

An actionable result communicates who is impacted, the scale of the harm, or the source of the issue. This allows stakeholders to intervene. Interventions might include:

- Developers: Changing the training data or fine-tuning the model.

- Companies: Deciding not to release a model or deploying safeguards.

- Regulators: Issuing fines or banning specific non-compliant applications.

- Users: Opting out of a system they know is biased.

Actionability is related to, but distinct from, concepts like interpretability or transparency. A metric might be perfectly interpretable (you know exactly how the math works) but not actionable (the number doesn’t tell you if the model is safe to use).

The Desiderata: What Makes a Metric Actionable?

The core contribution of this paper is a framework for assessing whether a bias metric is actionable. The authors identify five key “desiderata”—or requirements—that a research paper should provide to make its proposed metric useful.

If you are a student or researcher developing a new metric, these are the five questions you must answer.

1. Motivation

The Requirement: Clearly state the need the measure addresses. Why it matters: Is this metric designed to detect direct discrimination in hiring? Is it for checking how a model handles a specific dialect? Or is it for a new language that previous metrics didn’t cover? If a user doesn’t understand the specific motivation, they cannot determine if the metric is right for their specific problem. A metric designed for “sentiment analysis” might be useless for “text generation,” even if both measure “gender bias.”

2. Underlying Bias Construct

The Requirement: Explicitly define what “bias” means in this context. Why it matters: “Bias” is a vague, overloaded term. It can mean statistical skew, social stereotyping, allocational harm (denying resources), or representational harm (demeaning a group). Actionability requires a theoretical understanding. If the paper doesn’t define the construct, the numbers are just noise. For example, if a metric claims to measure “gender bias” but only checks for binary pronouns (he/she), it is operationally failing to capture non-binary gender identities. Without a clear definition, a developer might think their model is “fair” for everyone, when it is only “fair” for a specific subset.

3. Interval and Ideal Result

The Requirement: Define the range of possible scores and, crucially, what an “ideal” score looks like. Why it matters: This is often the biggest pain point for practitioners.

- Domain: Is the score a real number? A percentage?

- Interval: Is it bounded between 0 and 1, or is it unbounded (like log-likelihood)?

- The Ideal: What is the target? Is 0 perfect? Is 50 perfect?

If a metric is unbounded (e.g., it can go from -infinity to +infinity), it is very hard to act on. If your score improves from 150 to 120, is that significant? Or is anything above 10 unacceptable? Without an “ideal result” (a normative standard), decision-makers cannot set thresholds for deployment.

4. Intended Use

The Requirement: Specify the conditions under which the metric works. Why it matters: No metric is a silver bullet. Some are designed specifically for Masked Language Models (like BERT) and won’t work on Generative Models (like GPT). Some require specific dataset formats (like stereotype pairs). By clearly stating the intended use—including necessary data, model types, and social contexts—researchers prevent misuse. Using a metric outside its intended scope is a recipe for false confidence.

5. Reliability

The Requirement: Provide evidence that the metric is consistent and robust. Why it matters: If you run the test twice, do you get the same result? If you change the seed words slightly, does the bias score flip? Reliability is a prerequisite for actionability. If a metric has a high margin of error, you cannot base a business or policy decision on it. Papers should report error margins, statistical significance tests, and robustness checks.

The Audit: How the Field Measures Up

To see if the NLP community is meeting these standards, the authors conducted a systematic literature review. They didn’t just cherry-pick famous papers; they followed a rigorous selection process.

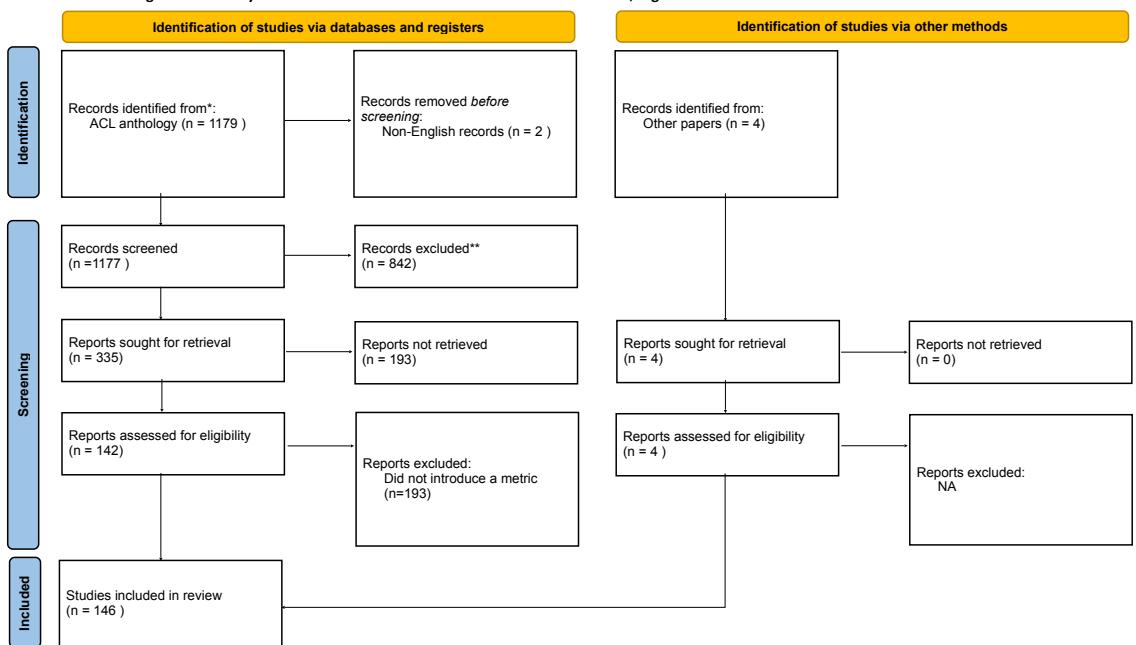

As shown in the PRISMA flow diagram below, they started with nearly 1,200 papers from the ACL Anthology (a major repository for NLP research). After filtering for relevance—specifically looking for papers that introduced a new bias metric or dataset—they narrowed it down to a final set of 146 papers.

The researchers then read every single one of these 146 papers and annotated them against the five desiderata of actionability. The results revealed significant “threats to actionability” across the field.

Threat 1: Vague Motivations

While 80% of papers provided some motivation, many were incredibly vague. A common pattern was circular logic: “We are introducing a new gender bias metric because existing metrics don’t measure this specific type of gender bias,” without explaining why that specific type matters in a real-world context.

Some papers cited underspecified “threats” without elaboration. For instance, one paper motivated its work simply by citing “LangChain” (a library for building LLM apps) as a hazard, without explaining what the specific risk was. If the motivation is unclear, a practitioner cannot know if the metric solves their actual problem.

Threat 2: The Missing Construct

Perhaps the most alarming finding was that in 25% of papers, it was impossible to identify what theoretical bias construct the authors intended to measure.

This ignores a fundamental rule of measurement: you cannot measure what you have not defined. Many papers skipped the definition and moved straight to operationalization, often simply copying a previous method (like the Word Embedding Association Test, or WEAT) without questioning if it fit their context.

When the construct is missing, “bias” becomes a mathematical abstraction rather than a social reality. This makes intervention impossible—you can’t fix a social harm if the metric only gives you a vector distance.

Threat 3: The Mystery of the “Ideal” Score

Most papers (82%) reported the range of their metric (e.g., “scores range from 0 to 1”). However, interpretation was often left as an exercise for the reader.

Only 32% of papers that engaged with an ideal result actually discussed what that result meant or how to interpret deviations from it.

The authors highlight a positive example from the “StereoSet” paper (Nadeem et al., 2021), which explicitly defined an IdealLM:

“We define this hypothetical model as the one that always picks correct associations… It also picks [an] equal number of stereotypical and anti-stereotypical associations… So the resulting lms and ss scores are 100 and 50 respectively.”

This level of clarity is rare. Without it, a user getting a score of “65” has no reference point. Is 65 close enough to 50? Or is it evidence of severe bias?

Threat 4: Ignoring Reliability

Reliability is the foundation of trust. If a thermometer gives you a different reading every time you touch it, you don’t use it to check a fever. Yet, the review found that reliability is largely ignored in bias metric development.

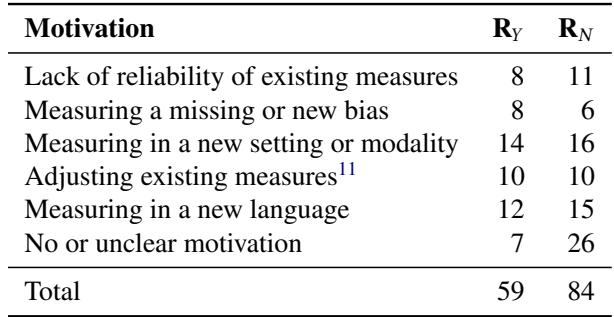

The table below breaks down the motivations of the papers compared to whether they discussed reliability.

As we can see in the table, only 28 papers (roughly 19%) explicitly discussed the reliability of their new method (indicated by the \(R_Y\) column).

Even more striking is the first row of the table. There were 19 papers that were specifically motivated by the lack of reliability in existing measures. Yet, of those 19 papers, 11 of them did not assess the reliability of their own proposed solution.

This suggests a troubling trend where researchers acknowledge that reliability is a problem in the field, introduce a “better” metric, but fail to prove that their new metric is actually more reliable.

Discussion: How to Fix Bias Metrics

The findings of this paper serve as a wake-up call. We are building a vast arsenal of “fairness tools,” but many of them are blunt instruments that don’t help us fix the underlying systems.

The authors offer several recommendations to move the field toward actionable science.

1. Ground Metrics in Impacts and Harms

Numbers are comfortable for computer scientists; social impacts are messy. However, for a metric to be actionable, the number must relate to a harm.

- Don’t just say: “The score is 0.8.”

- Do say: “A score of 0.8 corresponds to a 20% lower probability of a female candidate’s resume being ranked in the top 10.”

When results are grounded in expected behaviors, developers can make informed trade-offs between model accuracy and fairness.

2. Clearly Scope the Intended Use

Researchers need to stop implying that their metrics are universal. If a metric is designed for English-language news articles using BERT, state that. If it is applied to French medical records using GPT-4, it might fail completely. Explicit scoping helps users choose the right tool for the job.

3. Justify the Definition of Bias

We need to move away from “bias” as a catch-all term. Papers should articulate the specific construct they are measuring. Are they measuring “stereotypical associations”? “Toxic completion”? " exclusionary language"? Connecting the metric to a specific social construct (e.g., using literature from sociology or psychology) strengthens the validity of the work and clarifies what specific intervention is needed.

4. Reliability is Non-Negotiable

Finally, the community must demand reliability assessments. A new metric should come with error bars. It should be tested for stability against different seed words or slight paraphrasing of input sentences. If a metric is unstable, it is not just useless—it is dangerous, as it might give a false sense of security (or a false alarm) to model deployers.

Conclusion

The paper “Metrics for What, Metrics for Whom” introduces a critical vocabulary for the NLP community. By shifting the focus from validity (is the math right?) to actionability (can we use this?), it challenges researchers to think about the downstream consumers of their work.

For students and practitioners, the lesson is clear: Be skeptical of the score. When you encounter a bias metric, ask the hard questions. What is the ideal score? What is the construct? Is this reliable?

If the metric cannot answer those questions, it cannot help you build a fairer system. And building fairer systems is, ultimately, the only metric that matters.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-3373/images/cover.png)