Introduction

When we think about history, we usually visualize it. We picture the sepia-toned photographs of the late 19th century, the industrial smog of growing cities, or the fashion of the Victorian era. But have you ever stopped to wonder what the past sounded like?

Before the advent of recording technology, the auditory world was ephemeral. We cannot listen to a street corner in Copenhagen in 1880. However, we have “earwitnesses”—the authors who lived through those times and documented their sensory environments in literature. The novels of the Scandinavian “Modern Breakthrough” (1870–1899) are filled with the clatter of horse-drawn carriages, the hiss of new steam engines, and the murmurs of urban crowds.

For historians and literary scholars, analyzing these sounds offers a unique window into how society changed during rapid industrialization. But there is a logistical problem: finding every mention of a sound across hundreds of novels would take a human lifetime.

This brings us to the research paper “Noise, Novels, Numbers.” In this study, a team of researchers from the University of Copenhagen and UC Berkeley developed a computational framework to detect and categorize “noise” in literature. By combining topic modeling with fine-tuned Large Language Models (LLMs), they analyzed over 800 novels to reconstruct the soundscape of the 19th century.

In this post, we will tear down their methodology, explore how they taught a computer to recognize “noise,” and look at what the data tells us about the volume of the Victorian age.

Background: The “Auscultative Age”

To understand why this research matters, we need to contextualize the era. The late 19th century in Scandinavia was a period of radical transformation. Copenhagen’s population exploded, and new technologies—from trams to factories—invaded the auditory space.

Scholars often refer to this period as an “auscultative age.” This term borrows from medicine (listening to the body with a stethoscope) to describe an era where people became hyper-aware of their sonic environment. Noise wasn’t just background; it was a sign of modernity, progress, and sometimes, social decay.

The Challenge of Defining Noise

Before the researchers could train a model to find noise, they had to define it. This is harder than it sounds. In Sound Studies, noise is often defined subjectively—as “sound out of place” or unwanted sound. However, teaching a computer to understand “unwanted” is difficult because it relies heavily on the specific character’s mood or context.

Instead, the authors adopted a more operational definition: Noise is “silence-breaking.”

This broad definition includes:

- Deviant sounds: Screams, explosions, crashes.

- Neutral sonic events: Factory whistles, footsteps.

- Low-volume sounds: Whispering or mumbling, provided they are noted as breaking the silence.

The Corpus

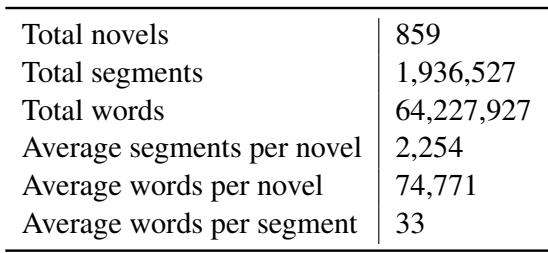

To “read” the soundscape at scale, the researchers utilized the MeMo corpus, a massive digital collection of Danish and Norwegian literature.

As shown in Table 1, the corpus is substantial. It contains 859 novels comprising over 64 million words. The text was broken down into nearly 2 million segments (chunks of text). This segmentation is crucial for machine learning, as it allows the model to analyze manageable pieces of context rather than swallowing an entire novel whole.

The Core Method: A Pipeline for Sound

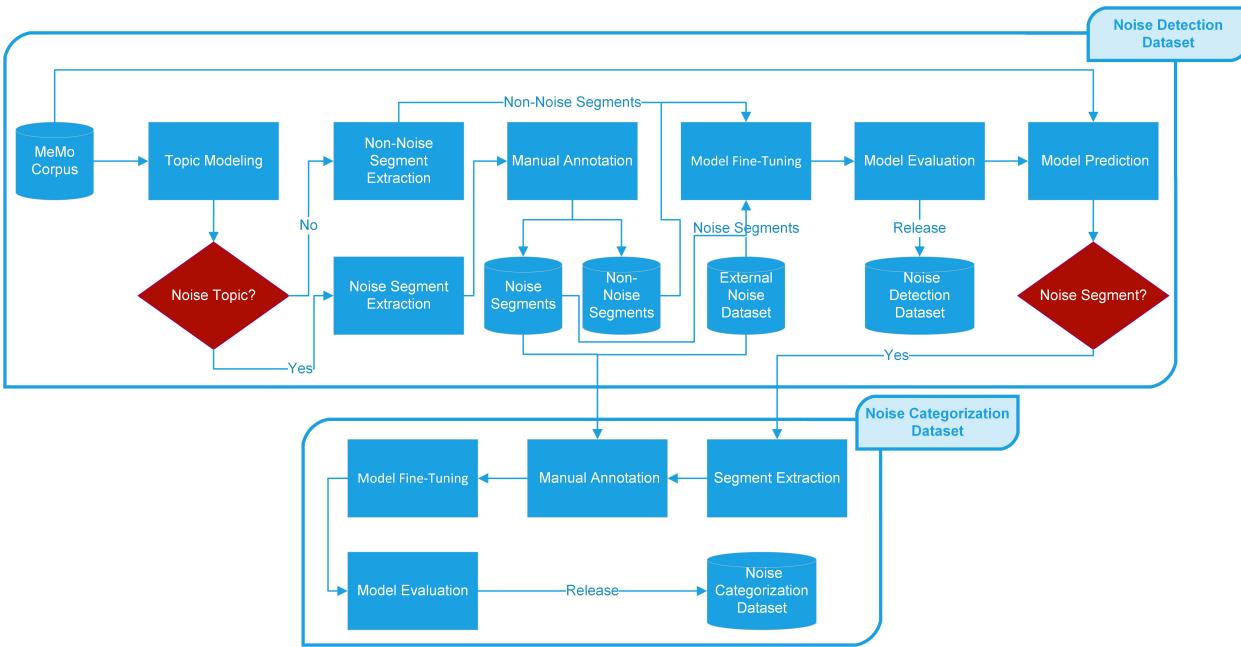

The heart of this paper is the methodology. The authors did not simply ask ChatGPT to “find the noise.” They built a rigorous, multi-step pipeline that combines unsupervised learning (Topic Modeling) with supervised learning (Fine-tuned BERT models).

The workflow is visualized in the flowchart below. We will break down each component of this process.

Step 1: Topic Modeling for Signal Extraction

The first challenge in a dataset of 64 million words is finding the needle in the haystack. Most paragraphs in a novel describe visuals, internal thoughts, or dialogue that isn’t explicitly “noisy.”

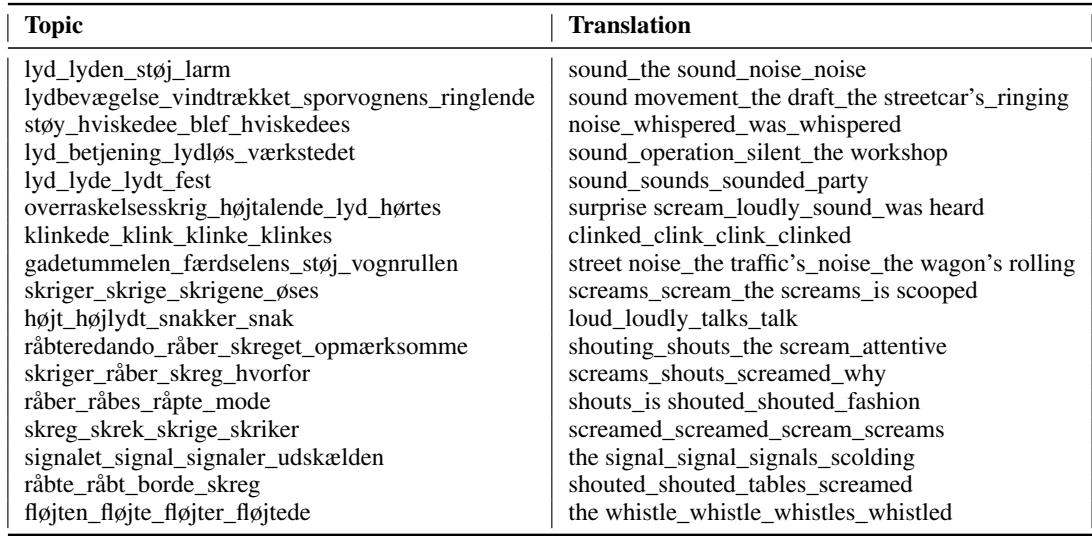

To filter the data, the researchers used BERTopic. This is a technique that clusters documents (or in this case, text segments) based on their semantic similarity. By analyzing the entire corpus, the model grouped segments into topics. The researchers then manually inspected these topics to find those related to sound.

Table 2 illustrates the effectiveness of this approach. The model identified clusters of words that clearly indicate auditory events. You can see topics revolving around “screams/shouts” (Topics 11, 12, 13), “mechanical sounds” like whistles and streetcars (Topics 2, 17), and general “noise/clamor” (Topics 1, 8).

From the millions of segments available, this filtering process narrowed the pool down to about 5,700 high-probability segments that were likely to contain noise.

Step 2: Human Annotation and Definition

Algorithms are only as good as the data they are trained on. To create a “ground truth” for the AI, human experts (historians and literary scholars) manually annotated a subset of the data.

They had to make binary decisions: Is this segment noise? (Yes/No).

They followed strict guidelines:

- Metaphors are not noise: “She felt a buzzing electric current” is a feeling, not a sound. This is labeled 0 (No Noise).

- Negation is not noise: “There was no noise” mentions the word “noise,” but describes silence. This is labeled 0.

- Music is noise: Following the “silence-breaking” rule, music counts as a sonic event.

This process created a training set where the model could learn the difference between the word “sound” used metaphorically and an actual description of a physical sound.

Step 3: Categorization

Detecting noise is step one. Understanding what made the noise is step two. The researchers went back to the data to classify the noise sources. This is vital for historical analysis—we want to know if the 19th century was getting louder because of people or because of machines.

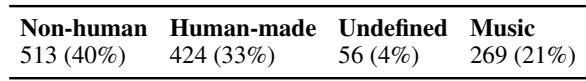

They established four categories:

- Non-human made: Nature (wind, thunder) and Machines (steam engines, trams). Note that even though humans operate machines, the sound itself is mechanical.

- Human-made: Voices, footsteps, screaming, applause.

- Music: Instruments and singing. This was separated because it’s distinct from “noise” in the traditional sense but is definitely a sonic event.

- Undefined: Ambiguous sounds where the source isn’t clear (e.g., “a generic hum”).

Table 3 shows the distribution of these categories in the training data. Interestingly, Non-human noise (40%) and Human-made noise (33%) are fairly balanced, which sets the stage for an interesting analysis of the full corpus later.

Step 4: Fine-Tuning Language Models

With a clean, annotated dataset in hand, the researchers moved to the modeling phase. They didn’t build a model from scratch; they used Transfer Learning.

They selected existing pre-trained models—specifically DanskBERT and MeMo-BERT (a model already adapted for historical Danish)—and “fine-tuned” them. Fine-tuning involves taking a model that already understands the Danish language and training it further on the specific task of recognizing noise segments.

This is akin to taking a student who is already fluent in Danish and giving them a crash course in “19th-century sound studies.”

Experiments and Results

The researchers ran two primary experiments: Noise Detection (Binary: Is it noise?) and Noise Categorization (Multi-class: What type of noise?).

Model Performance

How well did the AI perform? The primary metric used here is the F1-Score, which balances Precision (how many selected items are relevant) and Recall (how many relevant items are selected). An F1 score of 1.0 is perfect.

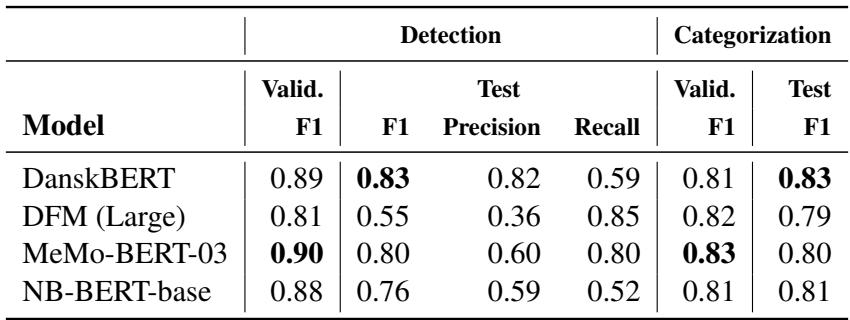

Table 4 reveals the results.

- DanskBERT was the standout performer. For Noise Detection, it achieved an F1 score of 0.83 on the test set. This is a very strong result for a literary task, where language can be subtle and poetic.

- For Noise Categorization, DanskBERT again achieved an F1 score of 0.83.

Interestingly, MeMo-BERT, which was trained specifically on historical texts, performed slightly worse on the test set (0.80) than the general modern DanskBERT. The authors suggest that because DanskBERT was trained on a massive modern corpus, it might be better at detecting “modernity signals” or simply has a more robust understanding of general language structures that helps it generalize better to unseen data.

The Soundscape of the 19th Century

Once the best model (DanskBERT) was trained and verified, the researchers unleashed it on the entire MeMo corpus—all 1.9 million segments. This allowed them to plot the frequency of noise over time, turning literary analysis into data science.

Result 1: The Past Got Louder

The first major finding confirms the historical hypothesis: The late 19th century was becoming a noisier place.

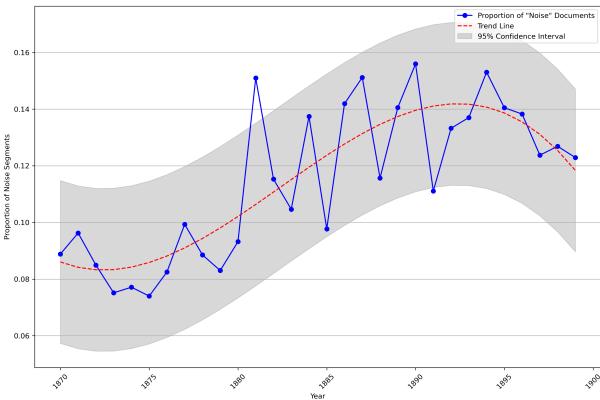

Figure 2 illustrates the proportion of text segments containing noise from 1870 to 1900.

- The Trend: The orange dotted trend line shows a clear upward trajectory. From the 1870s to the 1890s, there is a relative increase of more than 50% in noise-related segments.

- The Interpretation: This doesn’t just mean the world was louder; it means authors were writing about noise more. The sensory experience of the characters was increasingly defined by auditory interruptions.

- The Plateau: You’ll notice a slight dip or plateau around the turn of the century (1900). The authors speculate that noise might have become so ubiquitous that authors stopped noting it as remarkable—it became background.

Result 2: Who Made the Noise?

The second analysis looked at the types of noise. A common assumption about the Industrial Revolution is that machine noise would skyrocket while other sounds remained constant.

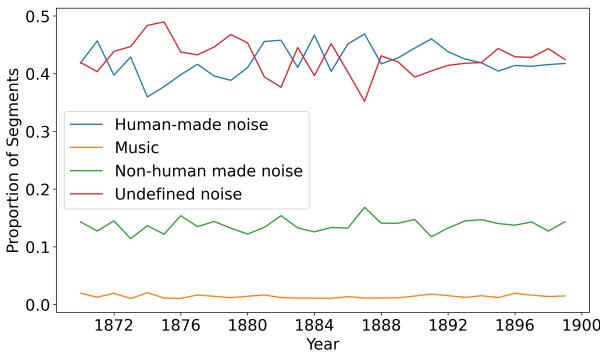

Figure 3 paints a more nuanced picture.

- Stability: Surprisingly, the distribution of noise types remains relatively stable.

- Human-Made Noise (Blue Line): This remains the dominant category, hovering around 40-45%. Despite the introduction of trams and factories, literary characters were still most obsessed with the sounds of other people—shouting, talking, and moving.

- Non-Human Noise (Green Line): This stays steady around 15%.

- Undefined Noise (Red Line): A large portion of noise is described abstractly.

Why is this significant? The persistence of human-made noise contradicts the idea that the “modern breakthrough” was solely about machines drowning out humanity. It aligns with historical records from cities like London and Paris, where “anti-noise” campaigns often focused on street musicians and shouting vendors rather than just industrial machinery. The literature reflects a society where human density was just as acoustically intrusive as the new technology.

Conclusion and Implications

The “Noise, Novels, Numbers” paper demonstrates the power of combining traditional humanities inquiry with modern computational methods. By training language models to “listen” to texts, the researchers were able to quantify a sensory experience that vanished over a century ago.

Key Takeaways:

- Methodology Works: It is possible to fine-tune standard BERT models to recognize abstract literary concepts like “silence-breaking events” with high accuracy (83% F1 score).

- History was Loud: The frequency of noise in Scandinavian literature increased by 50% during the late 19th century, reflecting the urbanization of the period.

- Humans are Noisy: Despite industrialization, human-generated sounds remained the most cited form of noise in novels, challenging the narrative that machines simply took over the soundscape.

This framework opens the door for fascinating future research. Could we map these sounds to specific neighborhoods in historical Copenhagen to see where the “noisy” and “quiet” districts were? Could we apply this to English or French literature to see if the “Auscultative Age” sounded different in London or Paris?

By turning novels into numbers, we don’t lose the art; we gain a new sense with which to experience it. We can finally hear the background hum of the past.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-3426/images/cover.png)