Introduction

Imagine you are building an AI application designed to role-play specific characters—perhaps a pirate, a formal butler, or a character from a video game like Genshin Impact. You grab a massive Large Language Model (LLM), but there’s a problem: to make the model sound exactly like your character, you typically need thousands of example sentences to fine-tune it.

But what if you only have 50 examples? Or 10?

In the world of Natural Language Processing (NLP), this is known as the Low-Resource Text Style Transfer (TST) problem. Traditional fine-tuning usually fails here, leading to overfitting or models that forget how to speak English entirely. Even powerful techniques like few-shot prompting with GPT-4 can be inconsistent or prohibitively expensive for production.

This brings us to a fascinating paper titled “Reusing Transferable Weight Increments for Low-resource Style Generation.” The researchers introduce a framework called TWIST. The core idea is intuitive but technically sophisticated: instead of learning a new style from scratch, why not “borrow” knowledge from other styles the model has already learned?

In this post, we will dissect TWIST to understand how it builds a “pool” of style knowledge and uses clever mathematics to transfer that knowledge to new, data-scarce tasks.

Background: The Challenge of Style Transfer

Text Style Transfer aims to rewrite text into a specific style (e.g., informal to formal, or neutral to Shakespearean) while preserving the original meaning.

The standard approach is Fine-Tuning. You take a pre-trained model (like T5 or LLaMA) and update its parameters (\(\theta\)) on a specific dataset to maximize the probability of the target style output (\(y\)) given an input (\(x\)).

However, updating all model parameters is computationally heavy and requires lots of data. This led to the rise of Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT), specifically LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation).

A Quick Primer on LoRA

To understand TWIST, you must understand LoRA. Instead of changing the massive weight matrix of the model directly, LoRA injects small, trainable rank decomposition matrices into the model.

Here, \(\theta_0\) is the frozen pre-trained weight, and \(\Delta \theta_t\) is the “weight increment”—the specific change needed to learn a new task. LoRA approximates this change as the product of two smaller matrices, \(\mathbf{A}\) and \(\mathbf{B}\).

The Insight: The researchers realized that these “weight increments” (\(\Delta \theta\)) contain concentrated style knowledge. If we could catalog these increments from various source tasks (like sentiment transfer or formality transfer), we could potentially mix and match them to jump-start learning for a completely new style.

The TWIST Framework

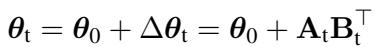

TWIST stands for reusing Transferable Weight Increments for Style Text generation. It operates in two main stages:

- Preparation: Building a library (pool) of style knowledge.

- Optimization: Retrieving and adapting that knowledge for a new, low-resource target.

Let’s look at the high-level architecture:

As shown in Figure 1, the system starts with a frozen Pretrained Language Model. It learns from various “Source Tasks” to create a “Source Weight Pool.” When an “Unseen Target Task” arrives, the system uses an adaptive retrieval mechanism to pull the most relevant weights from the pool, merges them, and initializes the model for the new task.

Let’s break down the technical innovations in each step.

1. Constructing the Weight Pool

First, the researchers train the model on several high-resource source tasks (tasks where they do have plenty of data). For each task, they learn a specific weight increment \(\Delta \theta_s\).

Once trained, these increments aren’t just tossed into a folder. They are organized into a Multi-Key Memory Network.

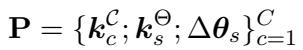

In a standard key-value store, you use a key to find a value. In TWIST, the “value” is the weight increment (\(\Delta \theta_s\)). But how do we define the “key”? The paper introduces a dual-key system stored in a structure \(\mathbf{P}\):

The storage \(\mathbf{P}\) contains:

- Weight Key (\(k_s^\Theta\)): A vector representing the specific semantic features of a source style.

- Cluster Key (\(k_c^\mathcal{C}\)): A vector representing a group of similar styles (clustered using spectral clustering).

- Value (\(\Delta \theta_s\)): The actual LoRA parameters.

This structure allows the model to search for knowledge both at a high level (“I need something formal”) and a granular level (“I need something specifically like this sentence”).

2. Adaptive Knowledge Retrieval

Now, imagine we have a new target sentence \(x\) that we want to transform into a new style (e.g., “Genshin Impact Role”). We don’t have trained weights for this yet.

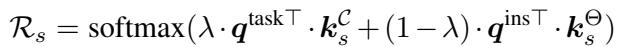

TWIST uses a frozen BERT model to extract features from the input text \(x\). These features act as a Query. The system compares this query against the keys in the memory pool to calculate a Retrieval Score (\(\mathcal{R}_s\)).

The equation above is crucial. The score \(\mathcal{R}_s\) determines how much “influence” a specific source style should have. It is a weighted combination (controlled by \(\lambda\)) of:

- Task-level similarity: How similar is the broad task?

- Instance-level similarity: How similar is this specific input sentence to the source style’s domain?

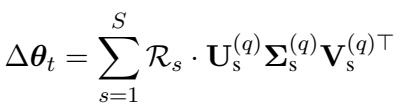

3. Reusing Weights with SVD

This is perhaps the most innovative part of the paper. Once we have the retrieval scores, we could theoretically just add up the LoRA matrices from the source pool.

The Problem: Naively adding parameter matrices often causes “parameter interference.” The weights from different tasks might conflict, creating noise that hurts performance rather than helping.

The Solution: The researchers use Singular Value Decomposition (SVD). They decompose the retrieved LoRA matrices and only keep the top-\(q\) singular values and vectors.

By reconstructing the weight increment \(\Delta \theta_t\) using only the most important singular vectors (matrices \(\mathbf{U}\), \(\boldsymbol{\Sigma}\), and \(\mathbf{V}\)), they essentially denoise the weights. It acts like a filter, keeping the strong style signals while discarding the noise that causes interference.

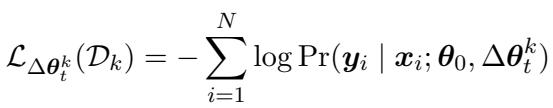

Finally, this constructed \(\Delta \theta_t\) serves as a warm initialization. The model is then fine-tuned on the small amount of target data available, minimizing the standard loss function:

Experiments and Results

To test TWIST, the authors used diverse datasets including Shakespeare (writing style), Genshin (role-playing 6 distinct characters), YELP (sentiment), and GYAFC (formality).

They compared TWIST against powerful baselines:

- Small-scale: T5-Large with standard fine-tuning and other transfer methods.

- Large-scale: LLaMA-2-7B using QLoRA and Few-Shot prompting with GPT-4.

Performance on LLaMA-2

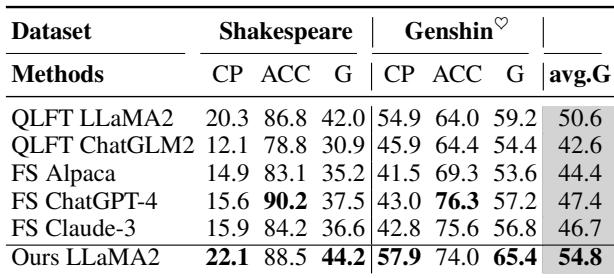

The results on large language models were impressive. Below is the comparison table for the full datasets.

Take a look at the G-score (Geometric mean of Accuracy and Content Preservation). TWIST (Ours LLaMA2) achieves a G-score of 54.8, outperforming standard QLoRA fine-tuning (50.6) and even beating Few-Shot ChatGPT-4 (47.4) and Claude-3 (46.7). This suggests that supervised initialization via TWIST is more stable than prompt engineering for style consistency.

The Low-Resource Breakdown

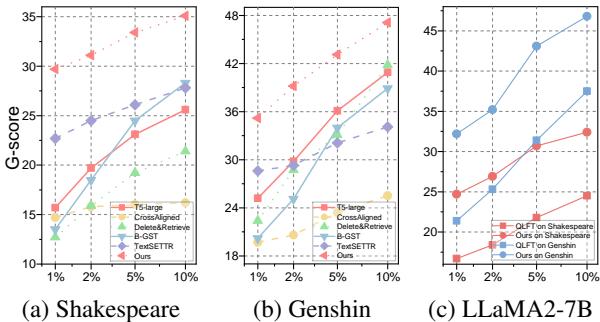

The real power of TWIST appears when data is scarce. The researchers simulated low-resource scenarios by using only 1%, 2%, 5%, and 10% of the training data.

In Figure 2(a) (Shakespeare), look at the red line (Ours). At 1% data usage, TWIST maintains a high G-score, whereas other methods (like CrossAligned or TextSETTR) completely collapse. In Figure 2(c), you can see the trajectory for LLaMA-2. Even with tiny amounts of data, the “warm start” provided by the weight pool allows the model to converge to a decent performance immediately.

Why does SVD matter?

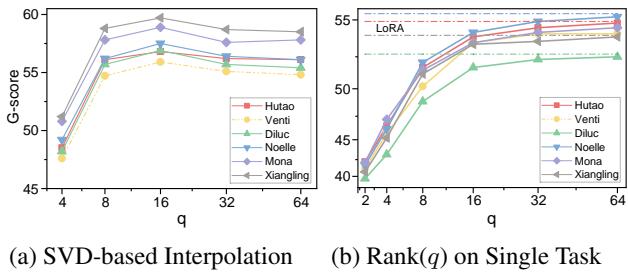

The authors claimed that using SVD to merge weights was better than standard merging. They proved this with an ablation study.

Figure 4 (left) shows the performance based on the rank \(q\). If \(q\) is too small (left side of x-axis), we lose too much information. If \(q\) is too large (right side), we introduce noise/interference. The sweet spot seems to be around \(q=16\). This validates the hypothesis that “sparse” merging is more effective than dense merging for transfer learning.

Visualizing the Style Space

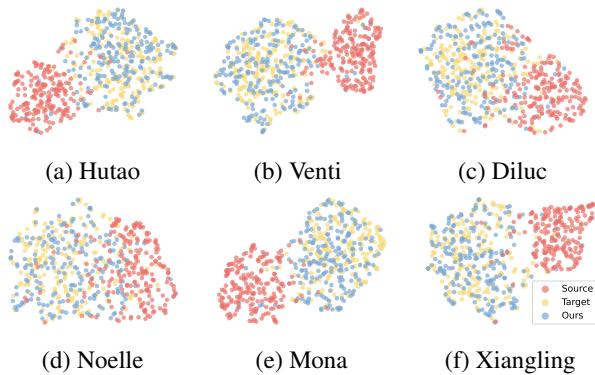

To confirm that the model is actually learning distinct styles, the researchers visualized the stylistic features of the generated text.

In these UMAP plots, the Red dots are the source text (original style), and the Golden dots are the target references. The Blue dots (TWIST output) overlap significantly with the Golden clusters. This visual confirmation shows that TWIST is successfully shifting the distribution of the text into the target style space.

Comparison to Other Methods

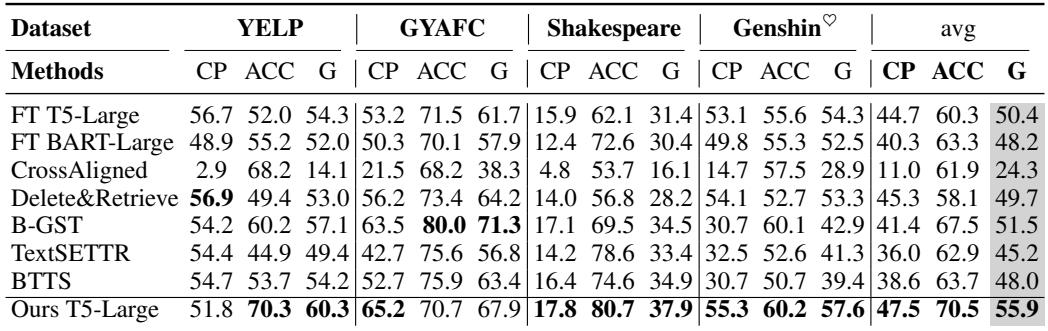

For completeness, here is how TWIST compares against other methods on smaller models like T5.

Even on T5-Large, TWIST outperforms the previous State-of-the-Art (SOTA) methods like “Delete&Retrieve” and “B-GST” across most metrics.

Conclusion

The TWIST paper presents a compelling argument for reusability in AI. Rather than treating every new style transfer task as a blank slate, we can treat “style” as a modular, transferable asset.

Key Takeaways:

- Don’t start from zero: Initializing a model with relevant weights from other tasks dramatically lowers the data requirement.

- Organize your knowledge: A structured weight pool with both task-level and instance-level retrieval allows for precise knowledge transfer.

- Merge smartly: You can’t just add neural network weights together. Techniques like SVD are essential to extract the useful signal and filter out the noise.

For students and practitioners, TWIST demonstrates that you don’t always need massive datasets or the largest proprietary models to achieve state-of-the-art results. Sometimes, you just need a smarter way to use the parameters you already have.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-3577/images/cover.png)