Introduction

We live in an era of data deluge. While we often think of “big data” as neat rows and columns in a spreadsheet or SQL database, the reality is far messier. A vast amount of the world’s knowledge—especially in fields like law, finance, and social sciences—is locked away in unstructured text. Think of court judgments, corporate announcements, historical archives, and policy documents. These documents contain crucial statistical information, but extracting that information into a structured table (a task known as Text-to-Table) is notoriously difficult.

For years, the Natural Language Processing (NLP) community has tackled this problem, but there has been a significant disconnect between academic benchmarks and real-world demands. Existing models might excel at converting a short Wikipedia biography into an infobox, but they crumble when faced with a 20-page legal judgment detailing a complex loan dispute involving multiple borrowers, guarantors, and interest calculations.

Why do they fail? Because traditional approaches often assume the table structure is simple and known in advance. They treat the task as a simple sequence generation problem. But in the real world, the structure is complex, the text is long, and the relationships are tangled.

In this post, we are doing a deep dive into a research paper that proposes a paradigm shift. We will explore TKGT (Text-KG-Table), a framework that redefines the text-to-table task. This approach introduces a new, challenging dataset derived from Chinese legal judgments and proposes a novel two-stage pipeline that uses Knowledge Graphs (KGs) as a bridge between raw text and structured tables.

By the end of this article, you will understand why traditional text-to-table methods struggle with complex documents, how Knowledge Graphs can guide Large Language Models (LLMs) to perform better extraction, and how this new method achieves State-of-the-Art (SOTA) performance.

The Problem with Current Benchmarks

To understand the innovation of TKGT, we first need to look at what was missing in the field. Until now, researchers primarily relied on datasets like Wikitabletext or WikiBio. These datasets generally involve short texts (often under 100 words) describing a single entity (like a person or a sports game). The goal is usually to generate a short description from a table (Table-to-Text) or vice versa.

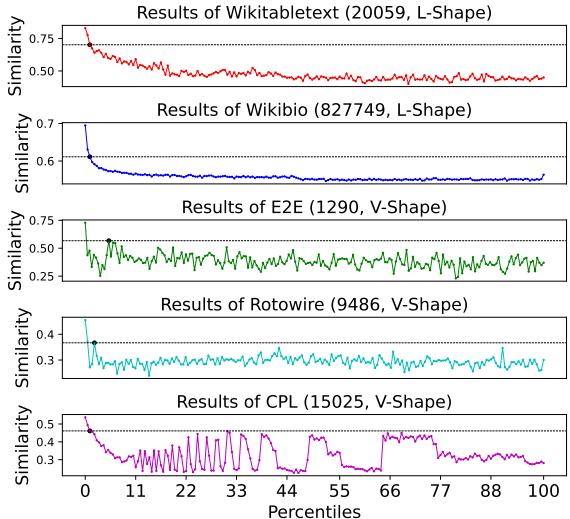

However, these datasets are “flat.” They lack the structural complexity found in professional domains. The authors of the paper performed a statistical analysis to visualize this gap. They looked at the similarity between the most frequent words in a text and the target fields in the table.

As shown in Figure 1, the results are striking:

- L-Shape (Top two graphs): Datasets like Wikitabletext and WikiBio show a simple downward trend (L-shape). This indicates that once you get past the very obvious keywords at the start, there is very little structural information hidden in the rest of the text. The text is essentially just a list of facts.

- V-Shape (Bottom graphs): In contrast, complex datasets like Rotowire (sports summaries) and the new CPL dataset (legal judgments) show a V-shape. The similarity drops but then rebounds and oscillates. This indicates that these texts have a “skeleton”—a deep structure where valuable information is scattered throughout the document, often mixed with structural words that don’t look like field names but are crucial for understanding the logic.

Real-world documents, particularly in social sciences, follow this V-shape pattern. They are long, logical, and semi-structured. Treating them like simple Wikipedia summaries is why previous methods failed.

Introducing the CPL Dataset

To address the lack of realistic benchmarks, the researchers introduced the CPL (Chinese Private Lending) dataset. This dataset is derived from a real-world legal academic project involving judgment documents from China.

Unlike a biography that describes one person, a legal judgment is an event involving multiple entities interacting with each other.

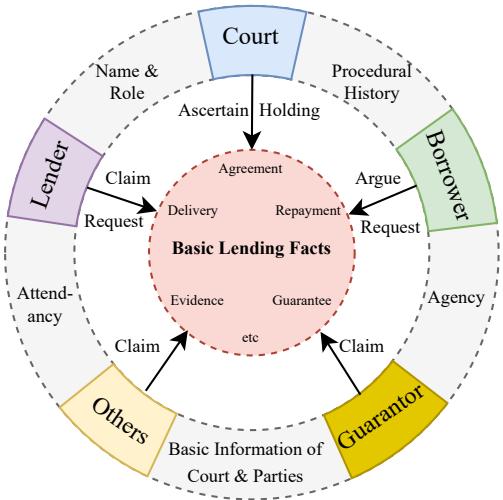

Figure 2 illustrates the complexity of the CPL dataset. It is not just a flat list of attributes. It is a web of relationships:

- The Core: “Basic Lending Facts” (Agreement, Repayment, Guarantee).

- The Entities: A Court, a Lender, a Borrower, a Guarantor, and Others.

- The Interactions: The Lender makes a claim regarding the repayment; the Court provides a holding regarding the agreement.

The text itself is lengthy (averaging over 1,100 words per document) and written in a specialized legal format.

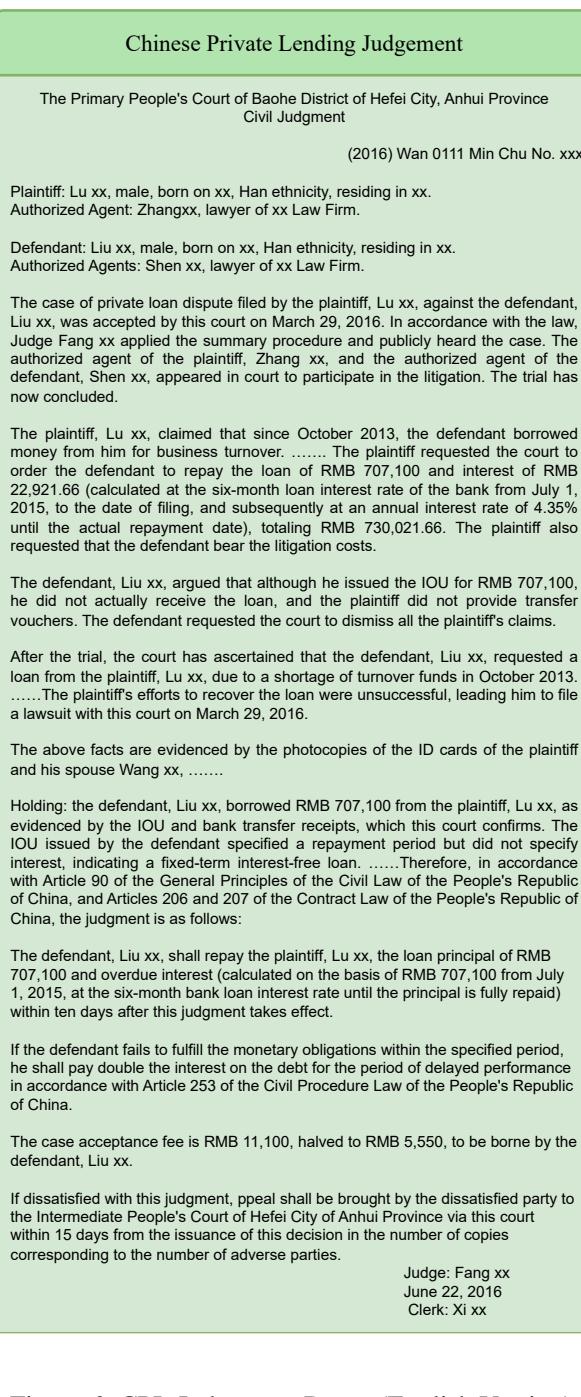

Figure 6 shows an example of the source text. It contains procedural history, specific claims about money, defenses argued by the borrower, and the final court ruling. Extracting a clean table from this requires understanding that “Plaintiff claims X” is different from “Court rules X,” even if they discuss the same amount of money. This dataset serves as the testing ground for the new method.

The Core Method: TKGT (Text-KG-Table)

The researchers propose that we cannot simply feed a 2,000-word legal document into an LLM and ask for a JSON output of a table. It’s too much context, and the model will hallucinate or miss details.

Instead, they propose TKGT, a pipeline that uses Knowledge Graphs (KGs) as “middleware.” The idea is to first map the structure of the text into a KG schema, and then use that schema to precisely extract data for the table.

As illustrated in Figure 3, the pipeline consists of two distinct stages:

- Mixed-IE Assisted KGs Generation: Creating the “blueprint” (schema) for the domain.

- Hybrid-RAG Based Tables Filling: Using that blueprint to retrieve data and fill the table cells.

Let’s break these down in detail.

Stage 1: Mixed-IE Assisted KG Generation

In this stage, the goal is not yet to extract specific names or dollar amounts, but to define what we are looking for. We need to construct a set of classes (e.g., “Plaintiff,” “Defendant,” “Loan Contract”) and relations.

The authors realized that relying solely on an LLM to “guess” the schema often fails. Instead, they use a Mixed Information Extraction (Mixed-IE) approach:

- Regulations (Rule-based): They leverage the inherent structure of the documents. For example, legal judgments often have fixed sections (Header, Fact-Finding, Reasoning, Verdict).

- Statistics: They analyze Term Frequency (TF) and Document Frequency (DF). Words that appear frequently in specific sections across many documents are likely to be key structural fields (e.g., “interest rate,” “principal,” “guarantee”).

- LLM Refinement: These statistical keywords and rule-based sections are fed into an LLM (like LLaMA-3). The LLM uses its internal knowledge to organize these keywords into a coherent KG schema (Classes and Relations).

This is a semi-automatic process. A human expert can review the draft KG schema and refine it. This “Human-in-the-loop” ensures high-quality field definitions without requiring the human to manually read thousands of documents.

Stage 2: Hybrid-RAG Based Table Filling

Once the KG schema (the classes and expected fields) is defined, the system moves to extraction. This is where the Hybrid Retrieval-Augmented Generation (Hybrid-RAG) comes in.

Standard RAG retrieves text chunks based on similarity to a query. However, TKGT does something smarter. It uses the KG structure to generate dynamic prompts.

The Logic of Extraction

The system iterates through the entities defined in the KG. It asks: “Do we have the name for the Borrower?” If not, it generates a specific query to find it.

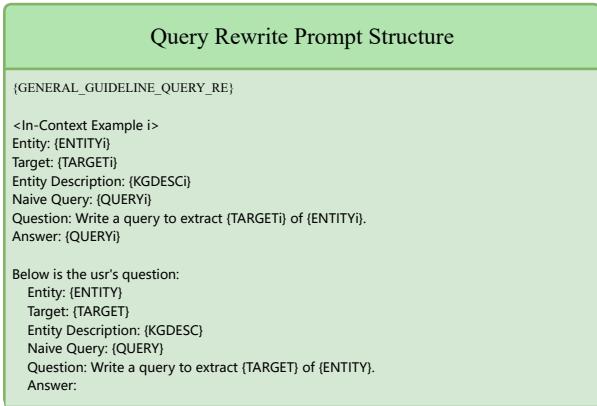

Crucially, the prompt isn’t static. It is rewritten dynamically to include context.

As shown in Figure 7, the system uses a Query Rewrite Prompt. If the system is looking for a specific target (e.g., the “repayment amount”), it doesn’t just search for “repayment amount.” It uses the entity description from the KG to formulate a precise query: “Write a query to extract the repayment amount for Defendant X.”

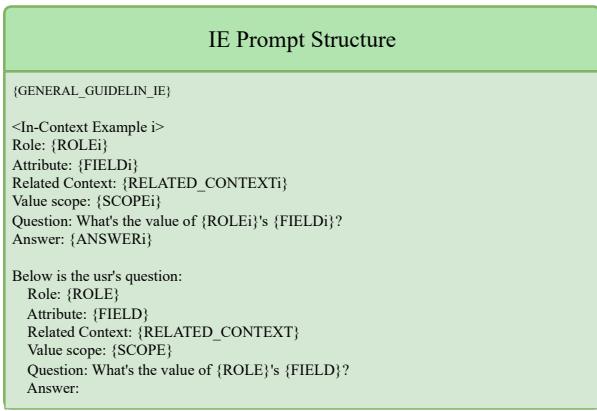

This retrieved context is then passed to the Information Retrieving Prompt.

In Figure 8, we see the final step. The LLM is given:

- The Role (e.g., Borrower).

- The Attribute (e.g., Date of birth).

- The Related Context (retrieved via the previous step).

- The Question (“What’s the value of…?”).

This targeted Q&A approach is far more accurate than asking an LLM to generate a massive table in one go. It focuses the model’s attention on one specific cell of the table at a time, supported by evidence found in the text.

Experiments and Results

Does this complex two-stage pipeline actually work better than just asking GPT-4 to do it? The experiments suggest a resounding yes.

Evaluating Stage 1: KG Generation

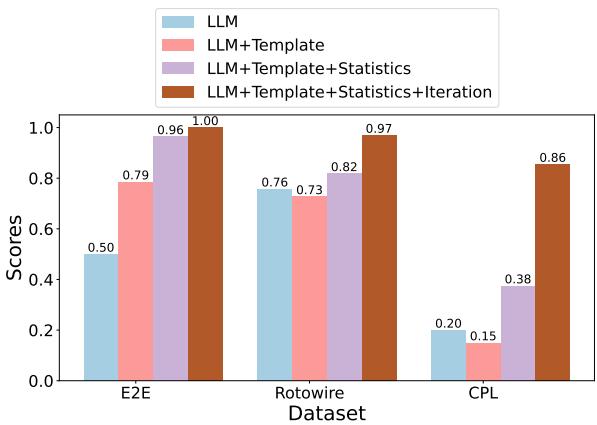

First, the researchers tested how well their method could define the table structure (the fields and headers) compared to a pure LLM approach.

Figure 4 compares four approaches:

- LLM: Asking the model to guess the fields zero-shot.

- LLM + Template: Giving the model a few examples.

- LLM + Template + Statistics: Adding the statistical keywords (Mixed-IE).

- LLM + Template + Statistics + Iteration: Allowing human feedback.

The results show that adding statistical insights significantly boosts performance, especially on complex datasets like CPL. The pure LLM struggles to identify the correct fields in complex legal texts, often missing crucial nuances that the statistical frequency lists reveal.

Evaluating Stage 2: Table Filling

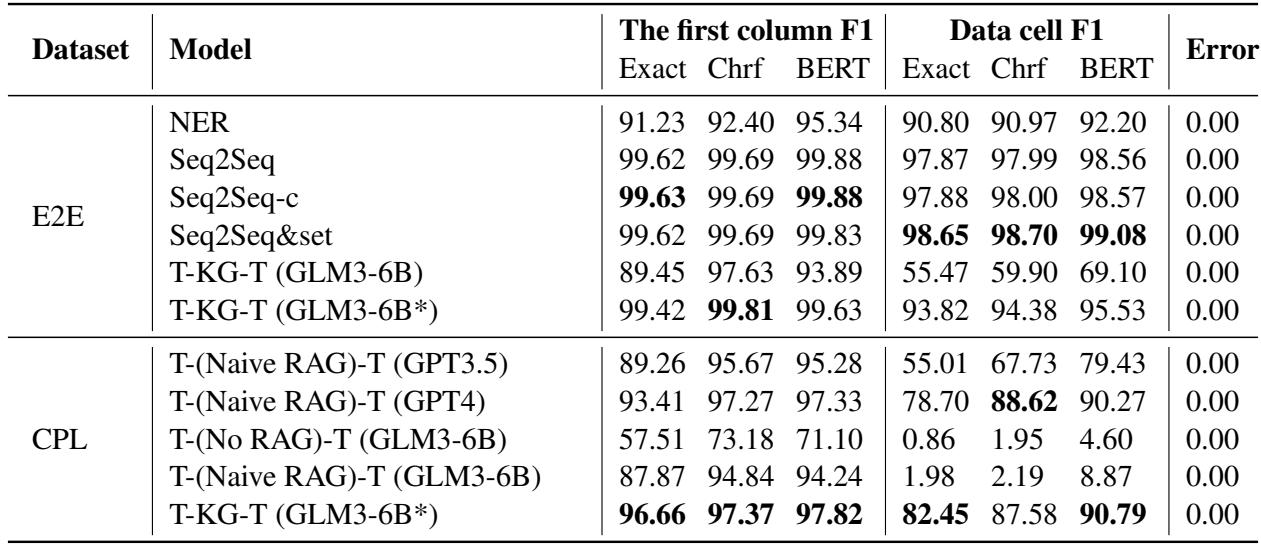

The ultimate test is filling the table with correct data. The researchers compared TKGT (using a smaller, fine-tuned model, ChatGLM3-6B) against massive commercial models like GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 using naive RAG.

Table 5 presents the results on the CPL dataset. The metrics used are F1 scores for the First Column (identifying the row/entity correctly) and the Data Cell (getting the value right).

- Commercial LLMs: GPT-4 with Naive RAG achieves a Data Cell F1 score of 88.62. This is quite good, reflecting GPT-4’s power.

- TKGT: The TKGT method, using a much smaller fine-tuned model (ChatGLM3-6B*), achieves a Data Cell F1 score of 87.58, which is competitive with GPT-4, and beats GPT-3.5 significantly (which only scored 67.73).

- Crucial Difference: Look at the First Column F1. TKGT scores 96.66, beating GPT-4’s 93.41. This means TKGT is better at aligning the data to the correct entity—a critical requirement in legal documents where mixing up the “Plaintiff” and “Defendant” is a catastrophic error.

For the Rotowire dataset (sports), TKGT achieved perfect scores in table header generation, solving a common problem where models generate tables with the wrong shape or columns.

Conclusion & Implications

The TKGT paper makes a compelling argument: when dealing with the messiness of the real world, we cannot rely on “black box” end-to-end generation.

By redefining the text-to-table task to account for long, semi-structured documents, the researchers have brought the field closer to practical utility. The introduction of the CPL dataset provides a much-needed benchmark for high-difficulty extraction tasks.

Most importantly, the TKGT pipeline demonstrates that structure matters. By using statistical methods to build a Knowledge Graph schema first, we provide the LLM with a roadmap. This roadmap allows for precise, RAG-driven extraction that outperforms larger, general-purpose models, particularly in aligning entities correctly.

For students and researchers entering this field, the takeaway is clear: Hybrid systems win. Combining the reasoning of LLMs with the structure of Knowledge Graphs and the precision of statistical analysis creates a system that is greater than the sum of its parts. This is the future of Digital Humanities and Computational Social Science—turning the chaos of text into the clarity of structured data.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-3697/images/cover.png)