Imagine you have deployed a customer support chatbot for an e-commerce platform. Initially, it performs one specific task—tracking orders—in English. Over time, your requirements grow. You need to add Spanish support. Then, you need to add a “Returns and Refunds” capability. Later, you expand to Hindi and Arabic.

In a traditional machine learning workflow, every time you add a new language or a new task, you might have to retrain your model from scratch on all data to ensure it doesn’t lose its original capabilities. If you only fine-tune it on the new Spanish data, it might suddenly forget how to speak English. If you train it on “Returns,” it might forget how to track orders. This phenomenon is known as Catastrophic Forgetting.

While researchers have studied how to add tasks sequentially (Task Incremental Learning) or languages sequentially (Language Incremental Learning), the complex intersection of the two—Task and Language Incremental Continual Learning (TLCL)—has remained largely unexplored.

In this post, we are diving deep into a paper titled “TL-CL: Task And Language Incremental Continual Learning”, which proposes a novel framework and a method called TLSA (Task and Language-Specific Adapters). This approach allows models to learn a matrix of tasks and languages efficiently, scaling linearly rather than polynomially, without needing to store petabytes of historical data.

The Problem: The Matrix of Tasks and Languages

To understand the innovation of this paper, we first need to define the landscape of Continual Learning (CL). CL is the practice of updating a model with new data without forgetting previously learned information.

In the context of Natural Language Processing (NLP), this usually happens in two dimensions:

- Task Incremental (TICL): The model learns new capabilities (e.g., Sentiment Analysis \(\rightarrow\) Question Answering \(\rightarrow\) Summarization) all in the same language.

- Language Incremental (LICL): The model learns to perform the same task in new languages (e.g., English \(\rightarrow\) Spanish \(\rightarrow\) Hindi).

However, real-world applications rarely move in straight lines. They move in a grid. You might need to add a new task in an existing language, or a new language for an existing task, or a completely new task in a completely new language.

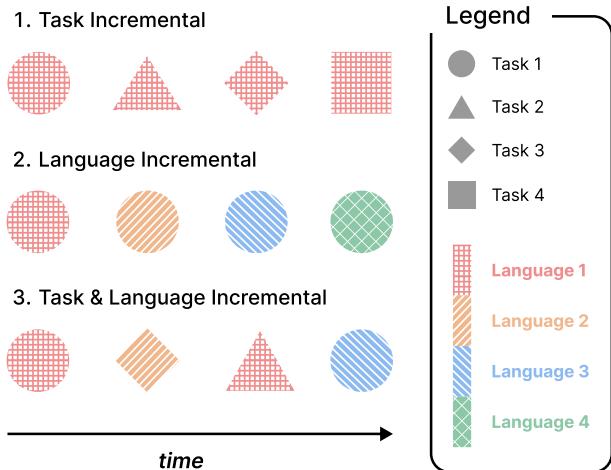

The authors visualize this complexity beautifully in the following diagram:

As shown in Figure 1:

- Row 1 (Task Incremental): We see different shapes (Tasks) appearing sequentially, but the texture (Language) remains the “Red Grid.” The model learns Task 1, then Task 2, etc., all in Language 1.

- Row 2 (Language Incremental): We see the same shape (Task) continuously, but the internal pattern changes. The model learns Task 1 in Language 1, then Task 1 in Language 2, and so on.

- Row 3 (Task & Language Incremental - TLCL): This is the focus of the paper. New shapes and new patterns appear. We might learn a Circle in Red (Task 1/Lang 1), then a Diamond in Orange (Task 3/Lang 2).

The goal of TLCL is to update a pre-trained multilingual model (like mT5) to handle this stream of incoming task-language pairs while minimizing catastrophic forgetting and maximizing knowledge transfer.

The Proposed Solution: Task and Language-Specific Adapters (TLSA)

The standard approach to fine-tuning large models (like BERT or T5) is computationally expensive. Retraining all parameters for every new task is slow and requires massive storage. This led to the rise of Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT), where we freeze the massive pre-trained model and only train small “Adapter” modules inserted between the layers.

However, standard adapters have a flaw in the TLCL setting. If you train a specific adapter for every single “Task-Language” pair (e.g., one adapter for English-QA, another for Spanish-QA, another for Hindi-NLI), you face two problems:

- Polynomial Growth: If you have \(|T|\) tasks and \(|L|\) languages, you need \(|T| \times |L|\) adapters. As you scale, this becomes unmanageable.

- Limited Transfer: An adapter trained specifically for “English Question Answering” doesn’t easily share its “Question Answering” knowledge with Spanish, nor does it share its “English” knowledge with Summarization.

The authors propose Task and Language-Specific Adapters (TLSA).

The Architecture

The core insight of TLSA is to decouple the task knowledge from the language knowledge. Instead of one monolithic adapter, they insert two distinct types of adapters into the Transformer layers:

- Task-Specific Adapters (\(\theta_t\)): These capture the logic of the task (e.g., how to extract an answer from a context) regardless of the language.

- Language-Specific Adapters (\(\theta_l\)): These capture the syntax and vocabulary of the language, regardless of the task.

This separation transforms the complexity. When a new task arrives, you reuse the existing language adapters. When a new language arrives, you reuse the existing task adapters.

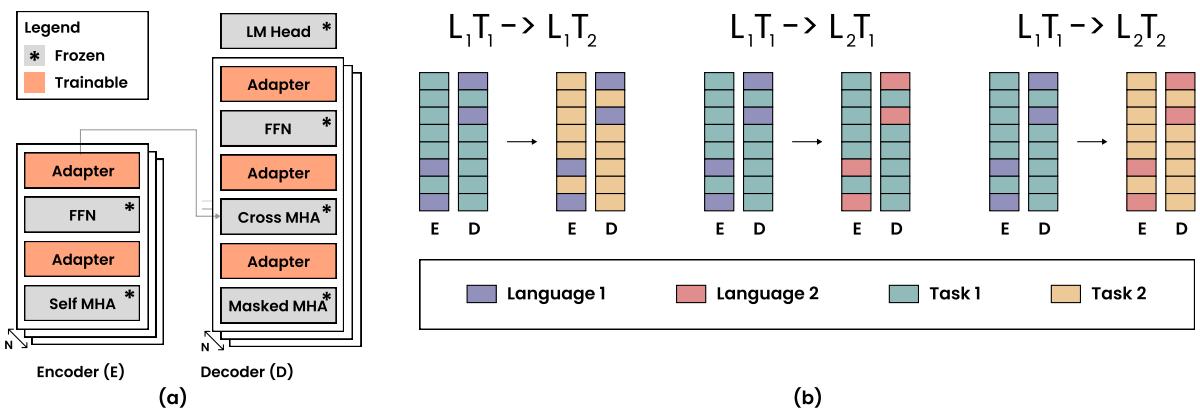

Figure 2 above illustrates this mechanism:

- Part (a): Shows where the adapters sit inside the Transformer encoder and decoder layers. Notice how both Task (Orange) and Language (not explicitly colored here but implied as separate modules) adapters modify the flow.

- Part (b): This is the crucial logic.

- \(L_1T_1 \rightarrow L_1T_2\): Same Language, New Task. We keep the Language Adapter frozen (purple bars) and swap/train the Task Adapter (teal to yellow).

- \(L_1T_1 \rightarrow L_2T_1\): Same Task, New Language. We keep the Task Adapter frozen (teal) and swap/train the Language Adapter (purple to pink).

- \(L_1T_1 \rightarrow L_2T_2\): Both change. We swap both.

The Mathematical Objective

To train these adapters without forgetting, simply separating them isn’t enough. The authors employ Elastic Weight Consolidation (EWC). EWC is a regularization technique that penalizes the model for changing parameters that were important for previous tasks.

When training for a specific task \(t\) and language \(l\), the objective function looks like this:

Let’s break down this equation:

- The Loss (\(\mathcal{L}\)): The first part

argminseeks to minimize the standard error on the current dataset \((X^{t,l}, Y^{t,l})\). It uses the base model parameters \(\theta_b\) (frozen), the task adapter \(\theta_t\), and the language adapter \(\theta_l\). - The Regularization (Concept): The terms following \(\alpha\) are the EWC regularization.

- If the task \(t\) has been seen before (\(t \in S_{tasks}\)), we add a penalty \(R(\theta_t, \theta_t^*)\). This prevents the task adapter from drifting too far from its optimal state \(\theta_t^*\) learned during previous sessions.

- Similarly, if the language \(l\) has been seen before (\(l \in S_{langs}\)), we penalize changes to the language adapter using \(R(\theta_l, \theta_l^*)\).

This allows the model to be “elastic”—it bends to learn new data but snaps back if it stretches too far away from the knowledge it needs for old tasks.

Why This Matters: Linear Complexity

The most significant theoretical advantage of TLSA is efficiency.

- Parameter Isolation (Standard): Requires \(|T| \times |L|\) adapters. If you have 10 tasks and 10 languages, you manage 100 adapter sets.

- TLSA: Requires \(|T| + |L|\) adapters. For 10 tasks and 10 languages, you manage only 20 adapter sets.

This linear growth (\(O(|T| + |L|)\)) makes TLSA highly scalable for massive multilingual systems.

Experimental Setup

To prove the effectiveness of TLSA, the researchers set up a rigorous benchmark.

The Model: They used mT5-small (Multilingual T5) as the backbone. The Tasks:

- Classification (cls): Sentiment analysis.

- Natural Language Inference (nli): Determining if statements contradict or entail each other.

- Question Answering (qa): Context-based extraction.

- Summarization (summ): Generating summaries.

The Languages: English (en), Spanish (es), Hindi (hi), Arabic (ar).

The Scenarios: They didn’t just test one easy sequence. They designed three difficulty levels:

- Complete Task-Language Sequences: Data is available for every combination of tasks and languages.

- Partial Task-Language Availability: Some combinations are missing (e.g., you might have English-QA but not Hindi-QA).

- Single Language Constraint: The hardest setting. No task or language is repeated immediately.

Results and Analysis

The authors compared TLSA against several strong baselines:

- SFT: Sequential Fine-Tuning (the naive approach, prone to forgetting).

- EWC: Regularization on the full model.

- ER: Experience Replay (storing a buffer of old data to rehearse).

- MAD-X: Another adapter-based framework.

- TSA: Task-Specific Adapters (only separate tasks, not languages).

- TLSA (Proposed): The method described above.

- TLSA\(_{PI}\): A variant of TLSA using Parameter Isolation (saving a copy of adapters for every pair—zero forgetting but higher memory).

Performance Comparison

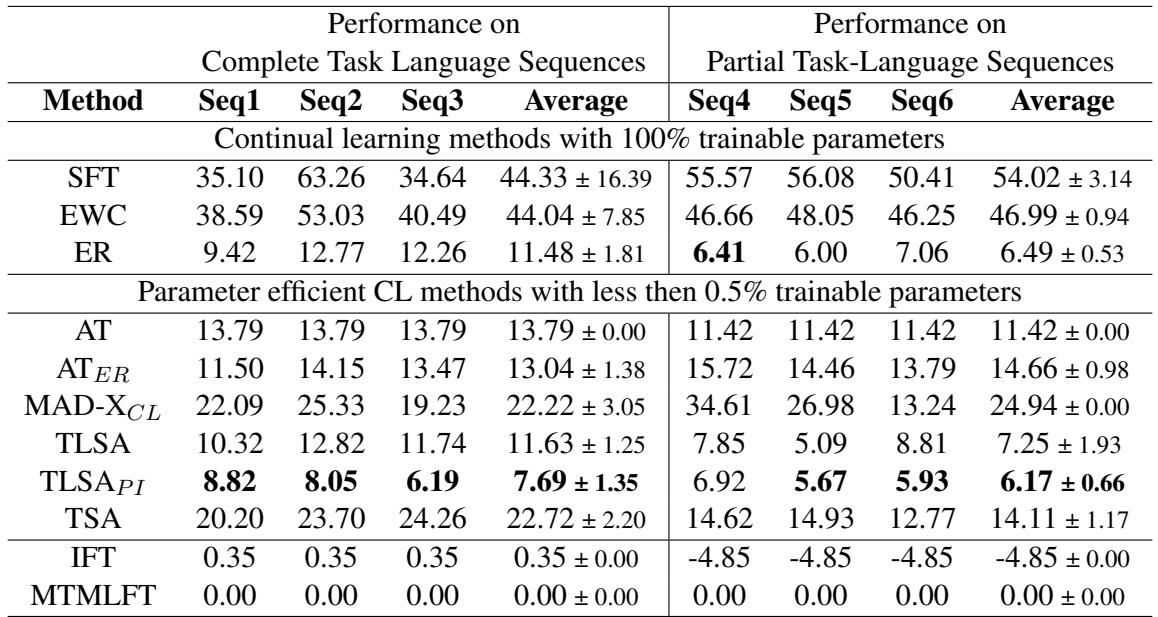

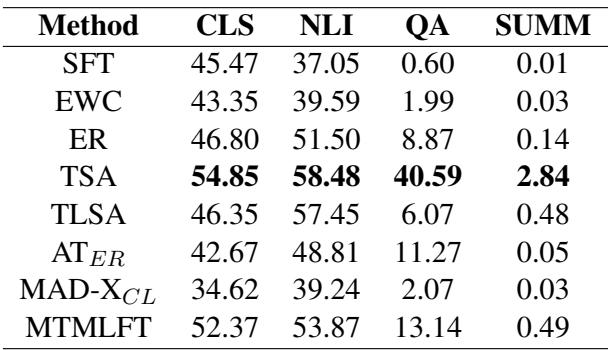

The primary metric used was PercentLoss, which measures how much worse the continual learning model is compared to a model trained on everything at once (the upper bound). Lower is better.

Looking at Table 1, we can draw several key conclusions:

- Naive SFT fails: With a PercentLoss of ~44%, simple fine-tuning forgets almost half of what it learned relative to the upper bound.

- ER is strong: Experience Replay (ER) performs exceptionally well (11.48% loss). Replaying old data is a powerful way to remind the model of the past, but it comes with the “privacy and storage cost” of keeping that data.

- TLSA dominates PEFT: Among parameter-efficient methods that do not use replay or save infinite copies of adapters, TLSA (11.63%) is the winner. It performs almost on par with Experience Replay.

- TLSA\(_{PI}\) is the champion: If you are willing to store separate adapter states (Parameter Isolation), TLSA\(_{PI}\) achieves the lowest loss (7.69%).

Does Cross-Transfer Work?

One of the main claims of TLSA was that separating tasks and languages would allow for better transfer. For example, learning “Question Answering” in English should improve the “Question Answering” adapter, which should then help when learning “Question Answering” in Hindi.

The authors verified this through an ablation study:

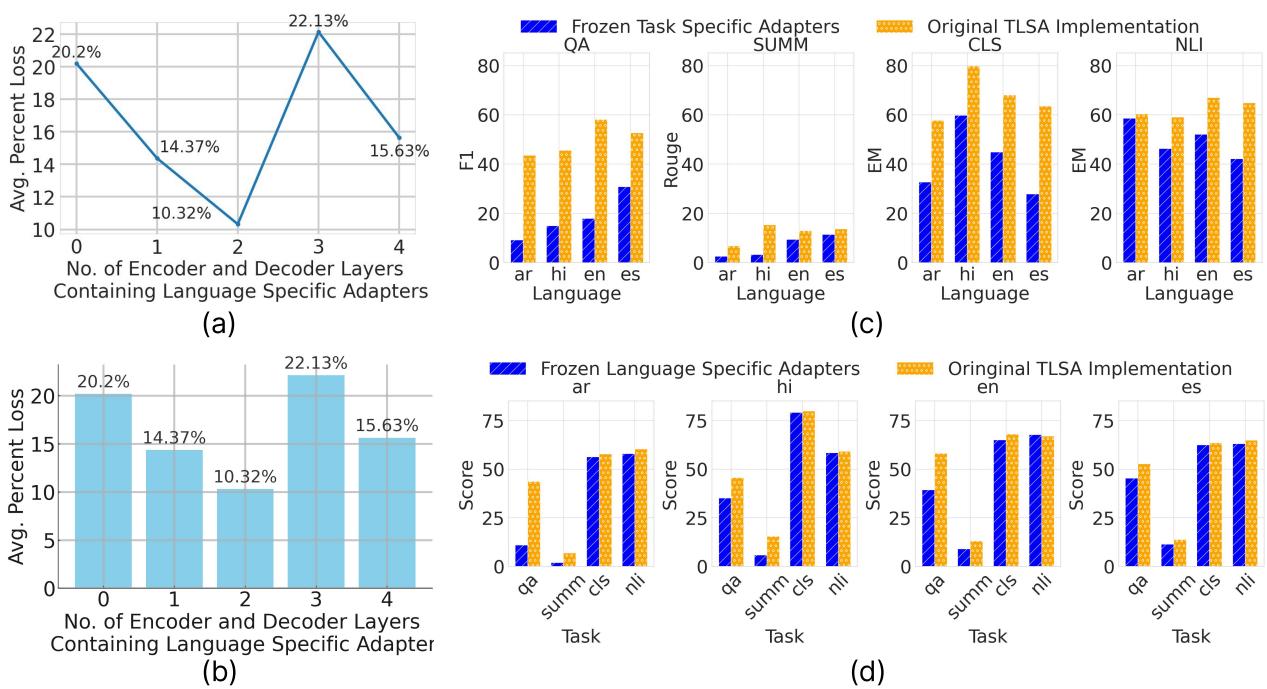

Focus on Chart (c) and Chart (d) in Figure 3:

- Chart (c) - Cross-Lingual Transfer: The authors took a pre-trained task adapter and froze it, then applied it to new languages (Blue bars). They compared this to the full TLSA training (Orange bars). The performance is remarkably close in many cases, proving that the Task Adapter successfully captured language-agnostic skills that transferred to new languages.

- Chart (d) - Cross-Task Transfer: Similarly, they froze the language adapters and applied them to new tasks. The high performance indicates that the Language Adapter successfully encapsulated linguistic syntax independent of the specific task at hand.

The Zero-Shot Limitation

While TLSA is excellent at incremental learning, the paper also investigated “Zero-Shot Generalization”—applying the model to a task-language pair it has never seen (e.g., training on English-QA and Spanish-NLI, then testing on Spanish-QA).

As shown in Table 3, most methods struggle here. While performance is decent for easier tasks like Classification (CLS) and NLI, it drops significantly for QA and Summarization. The authors note that models develop strong token biases. For instance, if a model sees Spanish only in the context of NLI, it struggles to generate Spanish summaries because its “Spanish representation” is overfitted to the NLI format. This remains an open challenge for the field.

Conclusion

The paper TL-CL tackles a realistic and messy problem: how to keep updating NLP models as they expand into new markets (languages) and new product features (tasks).

The proposed solution, TLSA, offers an elegant architectural fix. By treating “Task” and “Language” as separate, modular components, we can:

- Reduce Memory Growth: From polynomial to linear complexity.

- Enable Transfer: Leveraging English QA knowledge to improve Hindi QA.

- Prevent Forgetting: Using EWC to protect these modular components.

For students and practitioners, TLSA represents a shift in how we think about modularity in Deep Learning. It suggests that instead of training one giant “black box,” decomposing neural networks into semantic components (like “Language” blocks and “Task” blocks) is the key to building scalable, lifelong learning systems.

While Experience Replay remains a brute-force champion, TLSA proves that with smart architecture, we can achieve comparable stability without the heavy baggage of historical data.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-3698/images/cover.png)