The release of models like ChatGPT, GPT-4, and Claude3 marked a turning point in history. We now have Artificial Intelligence capable of writing poetry, debugging code, and drafting academic essays with a proficiency that rivals—and sometimes surpasses—human ability.

But this technological marvel casts a long shadow. The potential for misuse is significant, ranging from academic dishonesty in universities to the mass production of misinformation on social media. As these “weapons of mass deception” become more sophisticated, the line between human and machine authorship blurs.

This creates an urgent need: How do we reliably detect text written by an LLM?

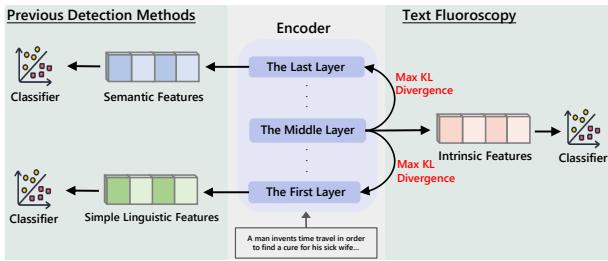

In this post, we will dive into a fascinating research paper titled “Text Fluoroscopy: Detecting LLM-Generated Text through Intrinsic Features.” The researchers propose a novel method that moves beyond looking at the surface of the text or its final meaning. Instead, they look “inside” the neural network—specifically at the middle layers—to find the “intrinsic features” that act as a digital fingerprint for AI generation.

The Problem with Current Detectors

To understand why this new method is necessary, we first need to look at how current detection systems fail. Generally, existing detectors fall into two camps:

- Semantic Detectors (The “Meaning” Approach): These look at the last layer of a language model (like BERT or RoBERTa). The last layer contains abstract, semantic information—the “meaning” of the text.

- The Flaw: Human and AI text often share the same meaning. If you ask an AI to write about climate change, its semantic content will look very similar to a human’s essay on the topic. These detectors tend to overfit to specific topics and fail when they encounter new domains.

- Linguistic Detectors (The “Syntax” Approach): These look at the first layer or use statistical patterns (n-grams). They analyze word frequency and simple grammatical structures.

- The Flaw: These features are fragile. If an attacker simply paraphrases the text (swapping synonyms or changing sentence structure), these detectors usually break.

The researchers behind Text Fluoroscopy argue that looking at the beginning (linguistic) or the end (semantic) is insufficient. The real secret lies in the journey between them.

The Core Insight: The “Middle” Matters

When a Large Language Model (LLM) processes text, it does so hierarchically.

- Early layers process simple syntax and word definitions.

- Later layers construct complex, abstract meanings.

The researchers hypothesize that the middle layers capture the transition process—how words are composed into sentences. This intermediate stage reflects the model’s unique “thought process” (or calculation process). While a human and an AI might end up with the same semantic meaning (Last Layer), the path the AI takes to get there through its neural network is fundamentally different.

The researchers call the features found in these layers Intrinsic Features.

As shown in Figure 1, previous methods rely on the extremes of the network. Text Fluoroscopy, however, targets the layer with the “Max KL Divergence”—essentially, the layer that is most distinct from both the raw input and the final output.

Text Fluoroscopy: How It Works

Let’s break down the mechanics of this method. It operates as a “black-box” detector, meaning it doesn’t need access to the internal weights of the specific model (like GPT-4) that generated the text. Instead, it uses a separate, open-source model (the encoder) to analyze the suspect text.

Step 1: The Setup

The system takes a piece of text \(x\). It passes this text through a pre-trained language model (the encoder) which has \(N\) layers.

Step 2: Projecting to Vocabulary

Usually, a language model only predicts the next word (token) after processing the text through all its layers. However, Text Fluoroscopy forces the model to predict the next word using the information available at every single layer.

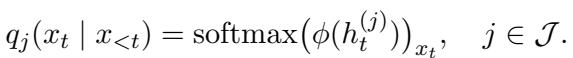

For any given layer \(j\), the method calculates the probability distribution of the next token. This essentially asks: “Based only on what you know at Layer 10, what do you think the next word is?”

Here, \(q_j\) is the probability distribution at layer \(j\).

Step 3: Finding the “Intrinsic” Layer

This is the most critical step. The system doesn’t just pick a random middle layer. It dynamically searches for the layer that represents the biggest “change” in information processing.

It compares the probability distribution of a candidate layer (\(q_j\)) against two benchmarks:

- The First Layer (\(q_0\)): Representing raw, shallow linguistic info.

- The Last Layer (\(q_N\)): Representing final, abstract semantic info.

It uses a mathematical metric called Kullback-Leibler (KL) Divergence to measure the difference between these distributions. The goal is to find the layer \(M\) that maximizes the difference from both the start and the end.

In plain English: We want the layer that is least like the raw input and least like the final output. This layer holds the unique “computation style” of the model—the intrinsic features.

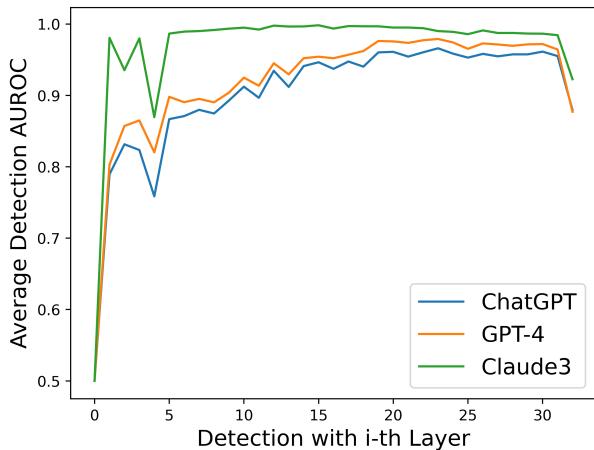

To visualize why this works, look at the graph below. It shows the relationship between the KL Divergence (left) and the detection accuracy (right) across different layers.

Notice the correlation? The KL divergence peaks in the deeper layers (around layer 25-30), and the detection accuracy (AUROC) follows the exact same trend. This confirms that the layers which are most mathematically distinct are indeed the best for detecting AI text.

Step 4: Classification

Once the optimal layer \(M\) is identified, the system extracts the “hidden state” features (\(h\)) from that layer. These features are fed into a simple classifier to make the final decision: Human or AI?

The classifier is trained using a standard loss function to minimize errors.

Experiments and Results

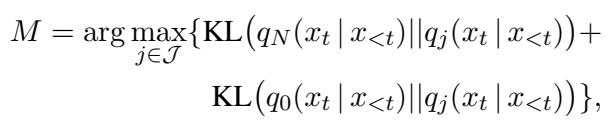

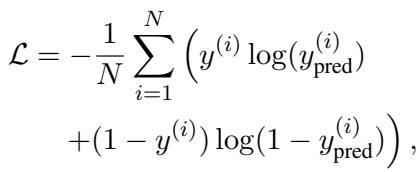

Does this theory hold up in practice? The researchers tested Text Fluoroscopy against a battery of state-of-the-art detectors, including RADAR, Fast-DetectGPT, and commercially available detectors like RoBERTa-large.

They used three diverse datasets:

- XSum: News summarization.

- WritingPrompts: Creative story writing.

- PubMedQA: Biomedical question answering.

And they tested against three powerful generators: ChatGPT (GPT-3.5), GPT-4, and Claude3.

Superior Detection Performance

The results were overwhelmingly positive. Text Fluoroscopy consistently outperformed the baselines.

Key takeaways from Table 1:

- GPT-4 Detection: This is notoriously difficult for most detectors. Text Fluoroscopy achieved a massive 7.36% improvement over the best baseline (Fast-DetectGPT) on average.

- Consistency: It scored above 96% AUROC across almost all models and domains. (AUROC is a metric where 1.0 is perfect and 0.5 is random guessing).

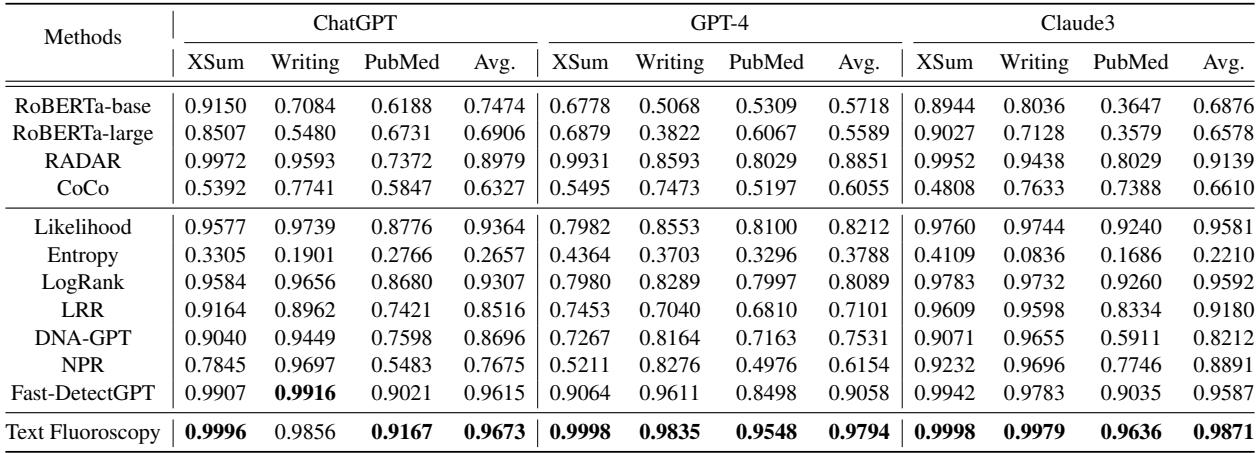

Why “Middle” is Better than “First” or “Last”

The researchers performed an ablation study to prove that the middle layers were doing the heavy lifting. They compared their dynamic middle-layer selection against simply using the first or last layer of the same encoder.

As seen in Figure 2, the “Text Fluoroscopy” bar (Blue) is consistently higher than using the First Layer (Green) or Last Layer (Orange). This validates the hypothesis that intrinsic features in the middle layers are more distinct than semantic or linguistic features.

Robustness Against Attacks

One of the biggest weaknesses of current detectors is that they can be fooled. If you ask an AI to paraphrase its own text, or if you translate the text to Chinese and back to English (Back-translation), the detection fingerprints usually disappear.

Because Text Fluoroscopy looks at intrinsic features—the deep structural processing of the text—it is remarkably resistant to these attacks. In their tests, even when text was aggressively paraphrased using a tool called DIPPER, Text Fluoroscopy maintained nearly 99% accuracy, whereas other tools saw significant drops.

Limitations and Future Optimization

There is one catch: Speed.

Because the original method calculates the probability distributions for every layer to find the maximum KL divergence, it requires more computation.

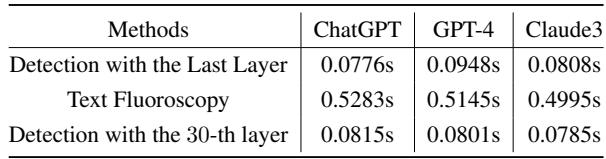

As shown in Table 4, the full Text Fluoroscopy method takes about 0.5 seconds per text sample, compared to roughly 0.08 seconds for standard last-layer detection. While 0.5 seconds is fast enough for a single user, it might be slow for processing millions of tweets.

The Solution: Hard-Coding the Layer. The researchers analyzed which layer was being selected most often. They found that detection performance generally peaks around the 30th layer of their encoder.

By simply fixing the method to always use the 30th layer (skipping the dynamic search step), they achieved a massive speedup—making it nearly as fast as standard methods—with less than a 0.7% drop in accuracy. This “Text Fluoroscopy (30-th Layer)” variant offers a practical balance for real-world deployment.

Conclusion

The “Text Fluoroscopy” paper provides a significant step forward in the arms race between AI generation and AI detection. It challenges the conventional wisdom that we should look at the “meaning” of a text to identify its author.

Instead, it teaches us that the process is just as important as the product. By peering into the middle layers of language models—the digital synapses where syntax transforms into semantics—we can find robust, intrinsic fingerprints that identify machine-generated text, even when that text is sophisticated or disguised.

As LLMs like GPT-4 and Claude3 continue to evolve, techniques like Text Fluoroscopy that rely on the fundamental architecture of these models, rather than surface-level patterns, will be essential for maintaining trust in digital content.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-3714/images/cover.png)